Revival in China : Resurgence of Traditional Folk Religion Sweeping Countryside

- Share via

DONGZHAI VILLAGE, China — Splashed on the entryway of the Shilun Buddhist Temple, fragments of once-bold but now barely visible yellow characters proclaim a fading message: “Eternal Loyalty to Chairman Mao. Utter Devotion.”

Inside the small roadside temple, the ghosts of Mao Tse-tung and his rampaging Red Guards seem long banished. Sticks of incense and peasants’ offerings of oranges are set before Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy. Painted on the altar is a guardian beast with green scales, hoofs and the head of a lion. Scenes from Buddhist stories cover the walls.

Here in South China’s Fujian province, the traditional heartland of Chinese folk religion, a resurgence of old beliefs is sweeping the countryside.

Other parts of China have also seen a restoration of religious practice over the last decade, as ancient ways reassert themselves after the fierce anti-religion campaigns of Mao’s 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution. But in much of this once primarily Buddhist country, it is a half-hearted revival at this point, limited by lingering anti-religious sentiment and a lack of resources for temple restoration.

Freedom of Religion

The Chinese constitution guarantees freedom of religious belief, but it also guarantees the right not to believe in religion. Public proselytizing is banned. Many Communist Party officials remain deeply opposed to what they view as ignorant superstitions that drain wealth from more productive uses.

Still, growing prosperity and weakened social controls in the coastal provinces of the south have provided particularly fertile ground for the rebirth of a wide range of village religious customs. Many have only the most tenuous relationship to formal Buddhism.

The Fujian countryside is dotted with innumerable tiny shrines, usually just a few feet in height, that honor local earth spirits. Most have been erected during the last four or five years.

Many villages have rebuilt old temples during this same period. Some are for worship of Buddhist figures. Others may be dedicated to local gods with special healing powers or ancient worthies of vague historical accomplishments. In some places, village committees have taken up collections to finance the construction. Wealthy Chinese overseas have also played a significant role in the religious revival.

Official Policy

Mixed in with the renewed religious life are other activities, such as fortune-telling, that still are vigorously opposed by the government. Much money is also going to construction of tombs in hillside cemeteries. Official policy favors cremation, but burial is traditionally preferred.

Many urban intellectuals view the survival of folk religion as an indication of rural superstition and ignorance.

“We have advocated democracy and science for 70 years, but we have achieved little,” complained an intellectual quoted by the official newspaper China Daily. “Where are democracy and science when thousands upon thousands of rural people are rebuilding Buddhas and lavishing money on graves?”

But the resurgent religious activity adds color, excitement and emotional comfort to village life.

In Dongzhai Village, a committee of elderly peasants organizes periodic celebrations at a tiny temple dedicated to the “Ancestral Lord of the Clear Water” and his partner, “Number-Two Ancestor of the Clear Spring.” Images of these spirits, resembling imperial officials dressed in flowing robes, are set amid lesser figures on an altar backed by a majestic painting of a dragon.

Set off Firecrackers

On festival days, hundreds of children gather to set off firecrackers, which serve the religious function of frightening away evil spirits, and the people of the village bring offerings of pork, rice and steamed dumplings to set before the images. Most of the food is later taken home and eaten.

Speaking with a visitor during a festival to honor “Number-Two Ancestor of the Clear Spring,” Su Jianlai, a peasant man who seemed to be in charge, explained the purpose of the activity by quoting an eight-character literary phrase: “Sincere faith will bring assistance. All wishes shall be granted.”

Su said that this temple, destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, was rebuilt by the peasants without outside assistance.

Many villages in this strip of coastal China, however, receive financial help for various projects, including temple reconstruction, from Chinese whose forebears emigrated to Southeast Asia or other parts of the world. Many Chinese who have prospered overseas have managed to maintain old traditions with greater integrity than has been the case in China. As these distant cousins renew ties with their ancestral villages, they fuel not only economic development but also the revival of ancient customs.

The people of Xijiang Village, for example, speak highly of a Chinese man from Indonesia named Li Xiexie, who contributed most of the money to rebuild a temple honoring Hua Guang Fu, a figure said by villagers to have lived long ago and performed many good deeds.

Money From Overseas

“The temple was completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution,” said Lin Fuzhao, 49. “It was rebuilt because of the belief of all the people of the village. Most of the money came from overseas Chinese, especially from Li Xiexie.”

Li has also contributed money to build a school and a clinic in the village, Lin said.

Although the legend of Hua Guang Fu is said to have originated with a historical figure, the centuries have transformed him into a god of healing.

“When adults or children get ill, he can bless and protect them,” said villager Lin Wenyong, 64. “We don’t know how he does it.”

Official ambivalence toward such religious practice sometimes leads to conflicts.

A Fujian radio station broadcast a report last year telling how a religious procession by more than 1,000 villagers, which involved carrying the image of a goddess, erupted into a battle with police in Shouning County.

Two People Wounded

“When they passed through the county seat, cadres and policemen of the public security office, together with personnel of the armed police corps, tried twice to dissuade and stop the procession,” the radio station reported. “The people paid no attention to the dissuasion, and clashed with the police. Two people were wounded.”

Authorities do not always seek to block public displays of religious fervor. Sometimes they cooperate, but this, too, can be controversial.

An unhappy policeman in central China’s Sichuan province wrote a letter to the official People’s Daily in which he described a scene in the local government courtyard of Liberation Township.

According to the letter, an itinerant religious teacher had arrived in the town, set up Buddhist idols in the government courtyard and enrolled disciples.

“There is the continuous sound of ‘wooden fish’ (a kind of wood-block percussion instrument), with the reciting and chanting of scriptures,” the policeman complained. “There are worshipers every day kneeling in front of a few clay idols, burning incense sticks and holy papers, and prostrating themselves before the image of Buddha. . . . The leaders of the government, rather than putting an end to this kind of activity, have provided accommodations.”

Hard to Sort Out

Even religious leaders can have a hard time sorting out what they should support and what should be opposed.

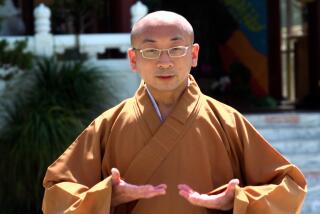

“In China, it is not easy to be clear about what makes up Buddhism, what constitutes the worship of spirits and what is superstition,” Yun Feng, head monk of the Six Banyans Temple in Canton, acknowledged in an interview.

“We oppose those things associated with spirit worship that aren’t good for the people,” Yun added. “Superstition can hurt people. For instance, if you are sick, eating ashes of the incense won’t cure your illness. You should see a doctor.”

China Women’s Daily reported that a mixture of superstition and belief in reincarnation led dozens of village girls in South China’s Jiangxi province to commit suicide in hopes of being reincarnated as sophisticated city women.

In mountainous areas of the province, the official newspaper reported, there had been 15 separate incidents of group suicides in which a total of 51 teen-age girls and young women killed themselves.

Many of the girls, depressed by poverty and lack of education, dressed in their best clothes and then threw themselves into lakes, believing that they would be reborn into a better life, the paper said.

A commentator for the Economic Daily, another official newspaper, complained bitterly about the temple-building boom, declaring that in some villages the temple is the best building and the primary school is the worst.

“Some poverty-stricken areas pinned their hopes of becoming rich on spiritual blessings, instead of relying on their own efforts,” the commentator said. “A pavilion for the ‘God of Heaven’ was built in a village when there was a drought. The villagers wanted to petition the god for rain, but while doing so they missed the right season for planting. . . . It is of no help to the collective or the individual to throw money into building useless temples.”

In some cases, there is no clear line between custom and faith, or between Buddhism and village worship of the myriad spirits of the countryside.

Among the most ubiquitous features of the Fujian countryside are little shrines honoring tudigong --lords of the earth. The shrines often hold a small image of an earth spirit, generally depicted as an old man with flowing beard, but such a figure is not essential.

“According to superstition, the tudigong is the local lord of wealth,” explained a peasant named Lin Wendan.

“Every family wants to put up a tudigong now,” said Wu Yumen, another peasant. “It protects people from danger. . . . It is to guarantee that when we do business, we can prosper.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.