The Social Dilemmas of Real-Life ‘Doogie Howsers’

- Share via

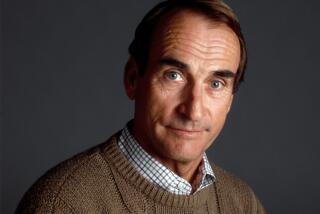

BALTIMORE — At the ripe old age of 24, Eric Strauch fondly recalls his college days. After all, we’re talking nine years ago.

Eric Strauch, M.D., as he’s known today, entered Johns Hopkins University at 15.

“I kind of just decided to go to college,” he says. Three years later he chalked up a biology degree. Philosophy beckoned, so a master’s degree at Georgetown University was added to his resume a year later. At 19 and with nothing better to do, Strauch thought: How ‘bout med school?

“The worst part of it,” says the fresh-faced surgeon, “is that I already look a lot younger than I am. People don’t believe I’m even 24. On the street, I look about 18 or 19.”

After graduating from the University of Maryland’s medical school in Baltimore, Strauch now is a second-year resident in surgery at the Veterans Administration Hospital here, certainly one of the youngest of his peers.

Second-year resident? Why, that’s just like “Doogie Howser M.D.,” the TV show that premiered recently and sparked new interest in prodigies. Produced by Steven Bochco, the show revolves around a perky 16-year-old who juggles the usual teen-age crises (Dad, when can I get a driver’s license?) with life as a resident two years out of medical school.

No Opinion--Yet

What does Strauch think? “I haven’t seen the show,” he says. “I had to work here last night.” In fact, Strauch would like to know where Doogie finds the time to have all those social encounters: You know, rappin’ with Dad and taking a 16-year-old cutie to the local sock-hop.

“I’ll put it to you this way,” says Strauch, when asked of his work schedule, “I was working here from Saturday morning to Monday evening at 8 p.m.” Strauch says he and his fellow surgery residents average “between 110 to 120 hours a week” at the hospital.

OK, but Doogie raises the burning question whether medical schools would allow a 16-year-old to graduate, or even enroll in the first place.

“My response would be no,” says Henry M. Seidel, MD, associate dean for student affairs at Johns Hopkins Medical School. “I’ve been here since 1943, and the youngest to enroll here that I know of was my roommate here, who was 19. But that was during the war, when they accelerated us along.”

Maturity Is Factor

Seidel, who has seen the show, and others involved in educating young doctors say a candidate’s maturity is a factor in qualifying for medical school. “Brightness is not everything . . . To be bright is simply not enough. It would be very unfair to take a 14- or 15-year-old young person and put them in a room alone with a 70- or 75-year-old man or woman.”

Others agree. “How would you feel if a 16-year-old walked in to do a physical on you?” says Tanya Friedman, an admissions officer at Harvard’s medical school. Friedman says the youngest student admitted to Harvard last year was 20. Four years ago, the school admitted an 18-year-old. “Remember, these people must have three years of college and fulfilled all the requirements. That’s very difficult,” she says.

But to Strauch it was no big deal. In high school at Bethesda, Md., he began taking college courses at George Washington University when his academic ability out-stripped that of his teachers. By the time he got out of high school, he had 34 college credits.

As a 15-year-old on the Hopkins campus, Strauch claims he had few problems adjusting to the older social life.

“It was more of a problem with women than with guys,” he says of his age, adding that his love life was hardly dean’s list. “I went through puberty as a college freshman.”

Typical Experiences

But whiz that he was, Strauch didn’t hole up like a bookworm when he got to college. “I joined a fraternity and drank a lot of beer and my grades weren’t in very good shape for a while,” he says. “At one time I had a 2.8 grade point average, until I built it up my senior year.”

The concern that academically accelerated youngsters will suffer social consequences is not necessarily justified, say some experts. “First of all, most young people do not have the kind of radical acceleration implied by the television program,” says Dr. William Durden, director of the Center for Talented Youth at Johns Hopkins, which identifies and nurtures extraordinarily bright youths from all over the world.

“There is an assumption, which has its roots in the ‘50s when bright kids were skipped a grade in school, that a person is equally talented at all disciplines,” he says. “That’s seldom the situation. You can have a person who is extremely gifted in math but average in verbal skills.”

‘Realm of Ideas’

Durden’s office, which is the largest of its kind in the world, tests youngsters at age 13, “when the human brain proceeds from concrete thinking to the abstract, the realm of ideas,” he says.

Once testing is completed, an educational package can be designed to allow the student to excel in his or her strong areas while developing normally in others.

In this system, Durden says, social problems are more likely to develop.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.