BOOK REVIEW : The Story of Brain Opiates--for Scientists Only

- Share via

Brainstorming: The Science and Politics of Opiate Research by Solomon H. Snyder (Harvard University Press: $22.95; 200 pages)

Science writers frequently debate whether it is better to be a writer who learns science or a scientist who learns to write.

In general--and with notable exceptions--specialists in all fields tend to write for other specialists, losing sight of the general reader. This is particularly true of scientists. They tend to write too narrowly, focusing on the trees rather than the forest.

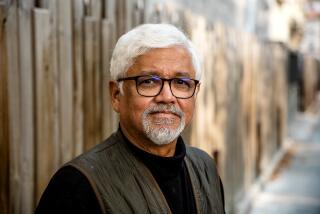

Solomon H. Snyder is a distinguished neuropharmacologist at Johns Hopkins University. In the early 1970s, he and his graduate student Candace Pert discovered opiate receptors in the brain--the places where opiates attach to nerve cells.

This was a major step in understanding the physical mechanism for overcoming pain and feeling good.

This discovery was one of the most important findings in brain research in recent decades. It paved the way for the discovery of endorphins--the body’s own morphine. For a while it was thought that this research would result in the synthesis of nonaddictive painkillers (which has not occurred).

“Brainstorming” is Snyder’s story of the research, which was carried on by teams of researchers in this country and abroad.

But despite its subtitle, “The Science and Politics of Opiate Research,” and despite occasional insights into the human world of science, Snyder’s book delivers less than it promises. He has fallen into the trap of writing for other scientists.

The work on opiate receptors and endorphins makes a compelling story, full of hard science and lots of human foibles. As it happens, the story has been told from different points of view in two other books published in recent years--”Apprentice to Genius” by Robert Kanigel (reviewed in this space on Dec. 23, 1986) and “Anatomy of a Scientific Discovery” by Jeff Goldberg (reviewed on May 20, 1988). Both were written by science writers, and both are better books than Snyder’s.

Kanigel and Goldberg capture the excitement of scientific research in a way that Snyder doesn’t. His writing is serviceable but flat, as if he is still writing for a scientific journal. (“Low concentrations of sodium markedly weakened the ability of MLF to compete for naloxone binding to opiate receptors.”)

Compare Goldberg’s description of the reaction of John Hughes, a researcher in Aberdeen, Scotland, when he and Hans Kosterlitz discovered the natural endorphins that bind to the opiate receptors: “Hughes was positively jubilant, . . . jumping up from the table at one point, and doing a little jig around the living room, singing in his monotone at the top of his lungs, ‘We’re going to be famous! We’re going to be famous!’ ”

Snyder’s best passages are the personal ones, where he reveals something about himself or how he thinks. (“I had little interest in caring for people’s diseased bodies when I became a medical student,” he writes at one point. “The M.D. degree, for me, was just a means to an end: becoming a psychiatrist. What I really wanted to study was disease of the mind.”)

But there aren’t enough such passages, and they seem appended to the narrative rather than integrated with it.

In addition, Snyder’s book omits important parts of the story. Pert was his graduate student and co-researcher in the original 1973 paper announcing the discovery of the opiate receptor. In fact, her name was listed on that paper before his.

But in 1978, when a Lasker Award--the American Nobel Prize--was given for the work, Pert did not share in it. It went to Snyder alone for the discovery of the opiate receptor and to Kosterlitz and Hughes in Scotland for the discovery of endorphins.

The exclusion of Pert touched off a very nasty and very public fight, leading to a severing of ties between her and Snyder.

Though she was a graduate student, she claimed that she had done more of the work than Snyder had and that she stood in the same relation to him that graduate student Hughes occupied in relation to Kosterlitz.

Both Kanigel and Goldberg recount this dispute is detail. Amazingly, Snyder doesn’t mention it at all, though Pert is very much in the book and he has a few less-than-complimentary things to say about her.

It is not clear whether Snyder is simply trying to remain above the battle or whether he regrets that Pert didn’t share the Lasker. Whatever the explanation, it is a glaring omission, and it makes you wonder what else he has left out.

Snyder’s book is not without value. It is full of the details of important research told by a key researcher. His speculations at the end about the physical bases of psychiatric disorders point to valuable future work. But if you only wanted to read one book on the subject, read one of the others.