School-Business Ties: The Unexamined Paradox of Past Performance : Education: If business wants graduates who can fulfill its needs, it must see the profound effect of economic despair on academic achievement.

- Share via

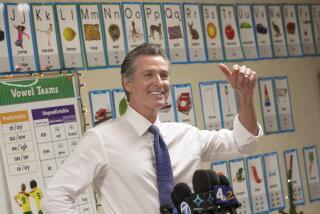

Picture Michael Milken, junk-bond king, standing before a blackboard in an inner-city school teaching a math lesson to two African-American youngsters. His visit is part of a “principals for a day” program that brings prominent business leaders into the classrooms so they can see the good and the bad firsthand. Such field trips are becoming common as talk of school-business alliances spreads throughout the country. School districts desperate for resources and business leaders worried about the education of a future work force are trying to find common cause.

There are reasons for hope about such alliances. Many schools need dollars, materials and repairs that business can provide. School-business alliances can lead to enriched internships and various kinds of mentoring relationships between promising kids and female and minority employees who could serve as role models. Beleaguered, low-status schools would benefit from having the support of powerful community figures.

There are also reasons for skepticism. Business might want to shape curriculum and testing. Even if such influence could not be exerted directly, schools might feel pressure to apply economic and industrial models to instruction and assessment. As a result, we could see a resurgence, with a ‘90s spin, of the pseudoscientific, efficiency-obsessed methods of the 1910s and 1920s, when teacher effectiveness was measured by, for example, the numberof arithmetic combinations that Johnny could perform in one minute. There is also the possibility that some businesses are interested in forming school alliancesto sell goods rather than stimulate reform.

But of more concern are two wider-ranging issues that have to do with the complex weave of economics, culture and schooling in America.

In all the public discussions I’ve heard, the focus of school-business alliances is solely on the problems with the schools and what it is that business can do to help remedy those problems. The discussion never seems to include business’ contributions to the conditions that have limited educational achievement. And it’s here that the image of Michael Milken before the blackboard begins to take on powerful added meaning.

Milken is a financial genius and a philanthropist of the first order. He also represents a trend in American business that many now agree has done more harm than good--a preoccupation with short-term interests. Although clearly not representative of all American business people, Milken brings into stark relief a fundamental contradiction in American business practice: its mix of philanthropy and short-sighted self-interest, its board-room rapaciousness and public generosity.

Business must examine this contradiction if it wants to enter educational reform in any major way. It would be a good thing for business to give money to the schools, but the schools also need business to consider broader issues of economy and culture.

If business is to help inner-city schools and schools in depressed rural and transitional areas, it will have to understand school failure within a socioeconomic context. It will have to ask itself hard questions about the way national economic policies and local business decisions have limited the development of communities, and the effect these policies and decisions have had on schooling. Schools in a number of cities--Detroit and Flint, Mich.; Gary, Ind.--have deteriorated as decisions by major industries have devastated their local economies.

The hope of a better life has traditionally driven achievement in American schools. When children are raised in communities where economic opportunity has dramatically narrowed, where the future is bleak, sealed off, their perception of and engagement with school will be negatively affected. We must ask whether, for example, donating a slew of computers to a school will make kids see the connection between doing well in the classroom and living a decent life beyond it when all they feel is hopelessness the moment they walk out the schoolroom door. From what I can see, the business community, perhaps because some of its members so cherish a Horatio Alger mythology, has not thought deeply about the profound effect economic despair can have on school achievement.

The business community must take a hard look as well at its apparent willingness to turn out virtually any advertising campaign that will help turn a profit and at the negative influence business interests exert on entertainment and news media. So many of the commercially driven verbal and imagistic messages that surround our young people work against the development of the very qualities of mind the business community tells the schools it wants the schools to foster. The coming era, we are told, will require greater and greater numbers of people who are critically reflective and can make careful distinctions, who can trouble-shoot and solve problems, who have an interpretive, analytic edge, who are willing to stop and ponder.

Yet young people grow up in an economy of glitz and thunder. The ads that shape their needs and interests champion appearance over substance, power over thought. Their entertainment, by and large, makes easy distinctions between right and wrong, the effective move and the blunder, and it trivializes intellectual work, from science to composing. The news they see highlights glamour and poise over knowledge and, now, blurs fact with “simulation.” And all this--from ads to MTV to news--turns on the titillation of quick movement.

Such tactics make money in the short run, but what effects do they have on youth culture over time? The relationship of mass culture and individual habits of mind is complex, to be sure. But there is a significant disjunction between the kind of youngster business says it needs from the schools and the kind of youngster one could abstract from the youth culture that is so powerfully influenced by business interests.

If business truly wants to positively influence the education of our children, the discussion must extend beyond the immediate needs of particular schools to the economy and culture in which those schools try to do their work. Business-school alliances will not result in fundamental, long-range educational change if the terms of the alliances essentially have the powerful bestowing momentary beneficence on beleaguered classrooms. We’ll need more than Michael Milken before the blackboard.