Getting the Rhythm : New Machines and the Latest Medicines Can Help an Irregular Heartbeat Go Steady

- Share via

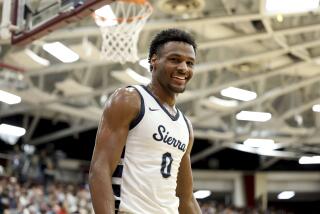

JUST EIGHT WEEKS ago, Hank Gathers, one of the nation’s top college athletes, collapsed on the basketball court. Two hours later, he was dead. He had been taking medicine to treat his heart condition--a cardiologist had prescribed a drug after Gathers fainted during a game in December--but it couldn’t prevent the irregular heart rhythm that led to his death.

Each year, 350,000 Americans die from sudden cardiac death, defined as death within one hour in a person who was otherwise medically stable. Many of these deaths result from a sudden irregular heartbeat caused by cardiovascular disease: hardening of the arteries. When one or more of the arteries that supplies the heart becomes blocked, an abnormal heart rhythm can result. This abnormality can prevent the heart from pumping properly, so blood may not be delivered to the brain and other vital organs. In the most severe instance, a person may lose consciousness.

Not all abnormal heartbeats are dangerous. A healthy person with a normal heart may experience an occasional extra beat, for example. But if an abnormal rhythm persists or if it causes symptoms such as fainting or chest pain, a potentially lethal condition that must be treated is present.

After Gathers’ fainting episode, he underwent several cardiac tests that indicated, during exercise, that his heart occasionally switched into a dangerous irregular rhythm. Doctors generally attempt to treat irregular heart rhythms, or arrythmias, in one of two ways: with medication or with electronic devices such as pacemakers. The medicines, known as antiarrythmics, are aimed at stopping or slowing irregular heartbeats. If standard medicines do not work for patients, doctors will turn to other, more powerful drugs, such as the new and highly potent antiarrythmic, amiodarone. Gathers was placed on propranalol, one of the most commonly used drugs for abnormal rhythms.

But none of the medicines is 100% effective, and all can produce unpleasant side effects. Propranalol, for instance, can cause patients to feel tired and weak and can sometimes lead to depression. Amiodarone’s side effects make it as difficult to take as certain forms of cancer chemotherapy. It can cause neurological problems, nausea and vomiting as well as lung and liver damage. Thus, amiodarone is rarely the first drug tried but is held in reserve for patients not helped by more conventional drugs.

Several months ago, Juanito Balaoing, a 51-year-old Los Angeles building inspector and father of two teen-agers, suffered an unexplained cardiac arrest. He survived, and after he underwent many tests and prolonged hospitalization, his doctors still had no clear explanation why his heart suddenly had begun beating in a haphazard manner.

Because Balaoing’s heart had already stopped once, his was at high risk for another sudden cardiac arrest. Studies have shown that for patients who survive a sudden stoppage of the heart, the likelihood of their suffering another episode can be as high as 40% within the first year. So, the choice of which medicine to prescribe was crucial. Although all heart medicines have been proven effective for some facet of heart disease, they do not work predictably for all patients. Rather than prescribe a drug that might work for Balaoing, doctors felt obliged to determine exactly which medication would work best for him through a complicated and risky procedure called an electrophysiologic study.

During such a study, the patient first is given a heart medicine designed to prevent abnormal rhythm, then is hooked up to sophisticated heart monitors. The doctor stimulates the heart muscle electrically, trying to induce the life-threatening rhythm. If the drug works, the stimulation should fail to produce a rhythm abnormality. In that case, the patient is sent home with a prescription for the tested medicine. But if the drug being tested fails, the abnormal rhythm that has been induced could be fatal, so doctors must be prepared to stop the dangerous rhythm by shocking the heart.

In Balaoing’s case, the electrophysiologic study did not clearly indicate that any of the medicines would be effective. At that point, his doctors considered implanting an automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, or AICD. This battery-operated device, about the size of a Sony Walkman, is a miniature-scale model of the large defibrillators used in emergency rooms. It monitors heart rhythm through three wires attached to the heart muscle. And it functions as a fail-safe system to restart a suddenly stopped heart, automatically providing a high-voltage shock that should return the heart to a normal rhythm. Implanting the AICD requires major surgery. It also is expensive, although the $50,000 cost is covered by most insurance plans.

Balaoing was more than willing to have the device implanted. “I didn’t want a metal box sitting in my belly,” Balaoing remembers, “but I realized that if I didn’t have the device and I was anywhere outside of an intensive-care unit, I could have a cardiac arrest and die.”

The device was inserted underneath the skin of his abdomen. “I constantly look like I am four months pregnant,” he says. “I had to buy all new clothes, and I still am quite self-conscious about the way I look.” Balaoing is lucky; his device has yet to discharge. But he lives in fear that it will go off while he is driving or in a public place. Upon discharge, a person experiences a sudden pounding in the chest as the device delivers a powerful electric shock to the heart.

“It’s very frightening when it goes off--like someone just threw a football at you,” says one woman who has an AICD. “But it’s even more frightening to realize that if it hadn’t gone off, you’d be dead.”

Recent studies have shown that the AICD can dramatically reduce the risk of sudden cardiac death for selected patients with hard-to-treat irregular heart rhythms. Patients with the device have a one-year mortality rate of about 2%, while patients treated solely with medications selected by electrophysiologic studies have a mortality rate of 10% to 40% after one year. Overall, doctors are optimistic about the AICD, viewing it as a highly effective treatment that has provided thousands of people with additional years of life.

For a patient to be considered for the device, there must be a reasonable suspicion that a lethal heart rhythm will recur, a belief that other treatments will not work and a willingness on the patient’s part to have the operation for implantation. And the machines are not without complications. Some patients experience lung or heart problems soon after surgery. The device may discharge for no apparent reason, and on rare occasions it may fail.

Researchers are developing a new generation of devices that are more sophisticated and potentially useful for other types of heart problems. New heart medicines that may improve survival rates are being tested. But so far, there is no treatment that can remove all the worries.