BOOK REVIEW : The Politicization of Medical Costs : THE MEDICAL TRIANGLE: PHYSICIANS, POLITICIANS, AND THE PUBLIC<i> by Eli Ginzberg</i> Harvard University Press $27.90, 301 pages

- Share via

Some years ago, I consulted a physician about a minor medical complaint. He immediately ordered $500 worth of tests, many of which seemed to have little or no relevance. When I asked whether all of that was necessary, he answered: “Don’t worry. The insurance company will pay for it.”

Thus was I brought face to face with the conspiracy between doctors and patients that fuels runaway medical costs. As a result, the United States spent some $500 billion on health care in 1987, more than 11% of our gross national product, a higher percentage than any other country. The government estimates that our medical bills will reach $1 billion by 1995 and $1.5 billion by 2000.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. May 2, 1990 For the Record

Los Angeles Times Wednesday May 2, 1990 Home Edition View Part E Page 9 Column 2 View Desk 1 inches; 26 words Type of Material: Correction

Medical costs--In Lee Dembart’s review Tuesday of Eli Ginzburg’s book, “The Medical Triangle,” the estimate for U.S. medical bills in 1995 should have read $1 trillion, not $1 billion.

Is this a sign that a wealthy nation can afford to keep itself healthy, or is it a sign that the whole thing is completely out of control? Eli Ginzberg, director of the Conservation of Human Resources Project at Columbia University, rejects the former explanation and leans toward the latter.

Doctors and patients are two sides of “The Medical Triangle” that Ginzberg describes and analyzes in his sober and bracing book, which argues that the situation has become so politicized that there is little chance of reining in the costs. The third side of his triangle is the government, which picks up 40% of the nation’s medical bill.

As Ginzberg explains, each of the sides of the triangle has different interests, which conflict with each other and which sometimes conflict internally.

The government, for example, has been trying desperately for nearly a decade to hold costs down. At the same time, however, one in every 13 workers in this country is now employed in the health-care system. They are an organized group, and they each have representatives in Congress. Whatever else members of Congress want in life, first and foremost they want to be reelected, which means using the public treasury to buy votes.

As Ginzberg tells it, the growth of medical insurance after World War II, coupled with the advent of Medicare/Medicaid in the 1960s, created a rising demand for medical care, which led to the production of more doctors, a boom in for-profit hospitals and the inability of anybody to say no.

No longer do doctors control American medicine. Ginzberg identifies a “destabilized” system of health-care delivery involving 10 power centers: the federal government, the states, the business community (which has balked at ever-increasing insurance costs), the hospital system (now a very big business), insurance companies, the legal system (and the threat of malpractice), organized consumer groups, for-profit hospital chains, foreign-trained physicians and the national political arena.

“The medical profession can no longer count on its erstwhile allies--hospitals, business, insurance companies--to keep the government at arm’s length in making decisions that affect health care,” Ginzberg writes. “Physicians are no longer the sole arbiters.”

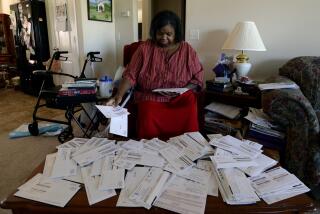

In the midst of all of this, Ginzberg notes graphically that the poor remain underserved. This is hardly surprising. Even a cursory look at the world will reveal that health care is just one of the privileges that money buys.

Ginzberg is not sanguine about the prospects for change. Our medical bills are increasing faster than inflation, and he believes that “there is an upper limit on the proportion of the GNP that the American people will be willing to spend on health care--possibly 15%, perhaps as much as 20%.

But he doubts whether the political will exists to put on the brakes. “Until we approach the upper limit of acceptable health-care expenditures--an eventuality that may be far in the future--cost-containment is likely to remain the elusive hare that the hounds pursue but never overtake.”

Needless to say, this is a public-policy issue of enormous significance, but like many such matters, it ranks with farm prices in its ability to stir people’s interest. Ginzberg’s writing doesn’t help. His book is well researched and well thought-out. But it’s a snooze.

Our country will owe an enormous debt to anyone who can figure out how to present this problem in an interesting way. More important, our country will owe an even-greater debt to anyone who can solve it.

Next: Jonathan Kirsch reviews “Making Peace With the Planet” by Barry Commoner.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.