Pottery May Depict Massive Explosion of Star 900 Years Ago

- Share via

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Long-sought evidence of a massive star explosion 900 years ago apparently has been found in a painting on an ancient piece of pottery excavated from an Indian village in southwestern New Mexico, scientists reported Tuesday.

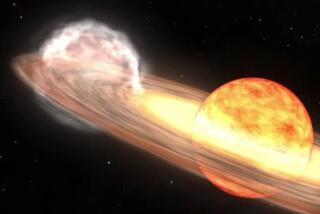

In an event so violent that debris from the blast can still be seen today, the explosion of the star created a giant cloud of gas and dust known as the Crab Nebula in the constellation Taurus.

Chinese and Japanese astronomers recorded the exploding star, known as a supernova, and those ancient records say the explosion was so bright it could be seen even in daylight for 23 days. A star explodes when it has nearly exhausted its fuel and collapses in on itself and erupts violently.

Astronomers have long searched for a similar record of the Crab supernova in the West, but no unambiguous evidence has ever been found.

However, astronomer Robert Robbins and one of his students, Russell B. Westmoreland, both of the University of Texas at Austin, told the American Astronomical Society here that they believe they have finally found a record of the supernova in a “burial plate” found at the site of the village of Galaz, home to a group of Indians known as the Mimbres.

The plate shows a sun-like object with 23 rays extending outward. Robbins said that is the only object among the 800 or so that he found that used the number 23, and he doubts that was happenstance because the Mimbres seem to have paid close attention to numerology in all their other works.

Robbins believes the 23 rays stand for the 23 days that the supernova was visible.

“I’m quite confident” of the finding, Robbins said. “The bowl is the most certain record of the supernova that has ever been discovered outside China and Japan.”

The pot was excavated in the 1930s but its significance escaped detection, Robbins said, until the Texas researchers came across it while studying the “archeoastronomy” of the Indians of the southwest.

Like many peoples who were dependent on predicting the changing of the seasons in order to know when to plant crops, the early Americans dabbled in astronomy, creating such things as celestial signposts that would alert them to the approach of summer or winter.

Thus some scientists have speculated that early pottery and cave drawings might have recorded the spectacular supernova of AD 1054. The exploding star, five or six times brighter than any other star in the sky, would have appeared before dawn on July 5 of that year.

There are drawings in at least two Southwestern sites that some astronomers feel could have referred to the supernova, but they are quite ambiguous. Robbins said Tuesday that the recent discovery strongly suggests that the other artifacts also point to the historic event.

Although many Indian tribes kept track of the seasons and paid attention to the sky, there is some evidence that the Mimbres carried it a step further than most.

“They may have been the most sophisticated astronomers in the Southwest,” Robbins said.

He bases that on a close examination of more than 800 pots and plates excavated from Galaz. Many of the artifacts carry what appear to be astronomical symbols and numbers--such as the frequent use of patterns of four, suggesting the four seasons.

But of particular significance is the frequent appearance of a rabbit, which Robbins says the Indians used as a symbol for the moon. The darker areas of the moon looked like the shape of a rabbit to the Indians, he said, and thus it became their lunar symbol.

“They saw a rabbit in the moon, not a man in the moon,” he added.

He said it is particularly significant that the sun-like object appears with the rabbit because the supernova would have followed the moon closely as the two rose over the horizon after the explosion.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.