NEWS ANALYSIS : Smith’s Win Wasn’t Big; Neither Was Bren’s Loss

- Share via

A court-appointed referee accepted heiress Joan Irvine Smith’s accusation that billionaire developer Donald L. Bren misled shareholders of the Irvine Co. when Bren purchased most of the stock in the giant Newport Beach development company seven years ago.

But his ruling Monday shows that the referee, Robert B. Webster, didn’t buy her main argument, that her shares were worth three times what Bren offered.

After years of legal wrangling, the referee awarded Smith $149 million for her stock, far less than the $330 million she’d asked for but a third more than the $114 million Bren had offered in 1983.

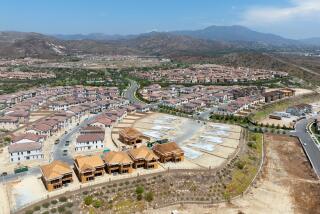

The case pitted two of the area’s wealthiest and most prominent citizens against each other: Bren, an intense, powerful billionaire who has changed the face of Orange County; and Smith, a combative, tough woman who traces her roots to one of the Southland’s largest ranches. At stake was the value of Irvine Co., a development firm that owns one-sixth of the county’s land.

The long-awaited decision left room for both sides to claim victory and to put the best spin on the outcome that they could. While Smith is walking away with $35 million more plus interest than previously offered, it’s also clear from the 90-page opinion that the company won many of the important points.

The referee, for instance, dismissed much of the testimony of Smith’s expert witnesses, saying that a prominent real estate consultant failed to “display an adequate understanding” of the big developer after he “spent only 76 hours on this engagement.”

Instead Webster relied mostly on the testimony of a consultant hired by Irvine Co.--Chicago’s Real Estate Research Corp.--in what was one of the largest such cases on record.

But the referee also said Bren hadn’t told shareholders that another prominent consultant they relied on to advise them on the value of their shares was actually working for him.

The Irvine Co. tried to argue that the other shareholders in the company--some of them high-powered executives such as auto magnate Henry Ford II and billionaire developer A. Alfred Taubman--wouldn’t have underestimated the company’s worth by $2 billion. They sold their shares for $200,000 apiece based on Bren’s estimate that the company was worth $1 billion, the company said.

Smith insisted that it was worth $3 billion and wanted $600,000 a share for her 11% of the stock. In a scathing attack on Bren, she accused him of stirring up discontent among the other shareholders, scaring them unnecessarily with bleak forecasts about the company’s health and conniving to buy the company on the cheap. It was a key part of her argument.

The court found that Bren, indeed, had not told other shareholders that a prominent accounting firm they were relying on for an estimate of the company’s value was actually working for Bren and helping him to buy the company.

The firm, Kenneth Leventhal & Co. of Los Angeles and one of its managing partners, Stan Ross, “had been retained by Bren to assist him in acquiring control of” the Irvine Co., the referee wrote in his opinion. “This was not disclosed to the selling shareholders.

“Had the selling shareholders been aware of Leventhal’s activities on Bren’s behalf, they may not have relied as heavily on Leventhal’s earlier computations.”

That “raises questions regarding the completeness and accuracy of the information relied upon by the selling shareholders,” the referee wrote. Ross was unavailable for comment Tuesday.

But it didn’t turn out to be a major victory for Smith. The referee said he agreed with her lawyers that he shouldn’t rely on the deal for guidance in setting a price for the company, but he wouldn’t ignore it either.

On the other hand, and more important, the judge rejected all three of Smith’s expert witnesses, whose estimate of the company’s value ranged from $2.6 billion to $3.3 billion.

One of the experts--Stephen Roulac of the Roulac Consulting Group, a prominent consultant and part of the San Francisco office of accountant Deloitte & Touche--showed “a failure to display an adequate understanding of (the Irvine Co.) or its assets,” the referee wrote.

That was “not surprising,” the referee wrote, “in light of his preparation. Roulac spent only 76 hours on this engagement prior to rendering his conclusion . . . “

Roulac responded Tuesday: “Clearly (the referee) didn’t follow or understand the testimony presented. What he did was take the approach of cutting the baby in half, rather than making a reasoned assessment of the facts.”

Roulac said other members of his firm had put in “thousands” of hours on the case.

“If our work doesn’t make sense, why do we have the major clients we have?” he said.

In the end, the referee largely accepted the testimony of the company, whose experts appraised the company at $1.22 billion. The referee adjusted that amount upward to $1.36 billion. Using that figure, the referee determined that Smith should receive $35 million more than Bren offered her.

But, says the Irvine Co., it has spent more than $15 million on the case and says Smith must have spent at least as much. Subtract that amount from the $35 million, the company says, and she’s only ahead $20 million. But the issue of who should pay the court costs--if anyone--has still to be resolved. That depends on whether one side can persuade the courts that the other acted in bad faith by provoking the lawsuit. A win on either side would, of course, bolster that side’s claim to victory.

Another big issue remaining to be resolved is interest on the $149 million: Smith says she should get as much as 18% based on the fact the company had the use of money it would otherwise have been required to pay her seven years ago. That could send the interest on her award into the tens of millions of dollars. The company says it should be much less.

No date has been set for a Michigan court to hear either issue, although a lawyer for the company said Tuesday that a hearing could come before September.

The Irvine Co. says it’s unlikely to appeal Monday’s opinion, which must still be certified--usually a formality--by the Michigan courts. (Irvine Co. is incorporated in Michigan.) A referee was appointed to hear the case so as not to tie up a courtroom with the trial, which ran 150 days from 1987 to 1989. Smith says she hasn’t decided whether to appeal yet.

If she doesn’t appeal, her 30-year battle with the company her great-grandfather founded to run the immense family ranch in Orange County will be nearly at an end, as will most of the family’s connections to the land.

The case, which pitted two of Orange County’s most familiar and richest names against each other, was closely watched over the seven years since the suit was filed. It pitted the feisty millionaire heiress against intense, reserved billionaire Donald L. Bren, the Irvine Co.’s chairman. Both said Monday they were elated by the outcome of the lawsuit.

The case revolved around how much the private company was worth in 1983--when Bren bought control--so a fair price could be determined for Smith’s shares. Since the company’s shares are not traded publicly, most of the long trial was consumed by each sides’ hired experts and their appraisals of the company’s vast landholdings. Smith said the company was worth more than $3 billion; Bren said $1 billion.

The opinion--which Webster, a retired judge, took more than a year to research and write--brought sighs of relief at the Irvine Co.’s Newport Beach headquarters. Smith had been asking--with interest--for more than $500 million, an amount even the big developer might have had to strain to pay.

“I’m sure they’re pleased they’ve avoided the Draconian consequences of a valuation in the range of $3 billion,” said Howard I. Friedman, Smith’s lawyer.

The company says it has budgeted up to $200 million to pay Smith the $114 million plus interest for her 11% stake in the company. It can easily repay the higher amount plus interest from lines of credit already established with the company’s lenders, the company says. The judgment, which must still be approved by the Michigan courts, won’t affect its timetable for developing its property, the company says.

“This won’t present any hardship to the company’s ongoing operations,” said Gary H. Hunt, Irvine Co. senior vice president. “We were carrying a range of numbers on our books, and this one falls well within that range.”

The opinion breaks new ground in the arcane legal field of valuation cases, said William B. Campbell, a lawyer for the Irvine Co. These cases occur most often when a private company is sold--as in this case--or an owner dies and the company’s tax liabilities are disputed by the heirs and the Internal Revenue Service.

The referee rejected as antiquated and narrow a legal doctrine called the “Delaware block,” Campbell said, which is often used to value companies in these cases and instead adopted what the Irvine Co. said was a more modern and broader approach to determining corporate value.

The company, which by a quirk of Michigan law was the plaintiff in the case, tried to argue that no appraisal of the company was necessary. The lawyers said that since Smith had rejected an offer to double her shares in the company when Bren bought out the other shareholders, she must believe the company was actually worth less than what Bren paid for it. Otherwise she would have opted to increase her shares at no cost, the Irvine Co. lawyers said.

The referee called that argument “irrelevant.” He said Smith had a right to reject both offers, the $114-million offer for her stock that she considered too low and the offer to double her shares. Her reasons, the referee said, didn’t matter under the law.

The referee called the testimony of Robert Flavell of consultant Flavell, Tennenbaum & Associates, who estimated the value of Irvine Co. land by comparing it to parcels that had sold recently, “questionable” enough to be “called into question.”

Michael Tennenbaum, Flavell’s partner, analyzed the company’s cash flow but based his estimate on “unreliable” assumptions of the company’s future earnings, the referee said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.