COLUMN ONE : Searching for Heart of Darkness : A woman’s tortured effort to find a brother who disappeared spans three continents. It leads to a mysterious--and possibly murderous--Amazon guide.

- Share via

BARCELOS, Brazil — Sandy Reed climbed out of the small airplane and squinted into the cloudless tropical sky. Paint was peeling off the deserted terminal. The Rio Negro, the largest tributary of the mighty Amazon, lay hidden behind a screen of trees. Only a rutted road sliced through the jungle.

Somewhere down that road lay the end of a quest--the end, if not the solution, to a mystery that had awakened Reed on countless nights, propelled her across three continents and drained her meager savings: the unknown, perhaps unknowable, fate of her brother, John Reed, who in 1980 disappeared somewhere beyond this silent clearing.

There had been rumors about him, purported sightings of a tall white man among the Indians, unconfirmable tales of a partial skeleton lying in a hammock beside the river, even allegations of murder. In the worst of her dreams, his frightened voice had told her, “It’s not like I thought it would be here.”

In the Amazon Basin, myths are as thick as vines, and its 2.5 million square miles remain today as impervious to the order and logic of civilization as in the year 1500, when Spanish explorer Vincente Yanez Pinzon recorded first seeing the river.

Armies and adventurers have sought their fortunes and their futures here. But the often impenetrable Amazon does not surrender treasures or truths readily. For five centuries, many who sought them have left empty-handed--or not at all.

John Reed, who hungered for some undefined higher knowledge and once wrote a book about UFO sightings, had come to believe in one of the countless stories of lost cities inhabited by ancient tribes, their location known only to a solitary guide. In this case, the guide was a shadowy figure called Tatunca Nara, the progenitor of this particular tale.

Reed was not the only one who thought there was a lost civilization to be found. Herbert Wanner, a 24-year-old Swiss who came to the jungle in 1984, was a believer, too. So was Christine Heuser, a middle-aged Swedish yoga instructor whose fascination with Indians led her to Tatunca Nara in 1987.

These three shared something else: One by one, they disappeared--murdered, some authorities believe--while in the company of Tatunca Nara.

Now, after retreating once in fear of her own life, Sandy Reed had come back to the Amazon--with a German filmmaker and a Times reporter along--to demand the truth.

The village of Barcelos, with its 3,000 residents, 10 cars and one telephone, lay before her, dirty and unwelcoming, on the edge of the Rio Negro. Television sets blared incongruously through open windows as she walked--in jeans, Reebok sneakers and a bush jacket--past dilapidated shacks and silent stares.

She stopped to ask directions from an elderly woman hanging wash on a wooden fence. She had only to speak the name of the man she sought. Everyone in Barcelos knew the legendary Tatunca Nara.

Tatunca Nara claimed to be the chief of a tribe that for 3,000 years supposedly had ruled Akakor, the capital of a lost civilization where descendants of gods were supposed to have lived in stone pyramids and subterranean shelters. He was born, he said, in the jungle near the border with Peru, the son of a German nurse who had been captured by Indians and taken by their chief to be his wife.

His tale became the basis for a book, “The Chronicle of Akakor,” written in 1976 by Karl Brugger, a German journalist based in Rio de Janeiro. The book described Akakor, its people and its history in alluring detail.

Over the years, Tatunca parlayed his legend into a business, leading tourists into the Amazon. He took them by boat along endless miles of postcard-perfect rivers and streams. He even served as guide for an elaborate expedition mounted by Jacques Cousteau, the famous French explorer-scientist.

Few who went into the wilds with Tatunca believed the story of Akakor; it merely added another layer of exotica to the adventure of a lifetime.

For some, however, Tatunca’s tale touched deeper chords. John Reed had gone so far as to have what Brugger’s book described as the symbol of Akakor, a sun rising out of water, tattooed over his heart.

When he vanished into the malarial jungle in 1980, John Reed, tall and blond, had left behind four hope-filled letters, his dog tags and his ticket back to the States. The last person known to have seen the 28-year-old man was his guide, Tatunca.

West German police say they suspect that Tatunca murdered Reed, Wanner and Heuser, although no charges have been filed and no bodies have been found.

The jungle has relinquished little evidence in this strange case. A jaw discovered by Swiss tourists in 1986 was identified through dental records as that of Wanner. About Reed, there have been only rumors; about Heuser, not even that.

The German police also suspect that Tatunca played a role in the death of Karl Brugger in 1984. Brugger was shot in the heart on a Rio street by a gunman who had demanded his money. A companion said Brugger was reaching for his wallet when the man shot him and ran off without taking anything. Rio police declared robbery the motive.

Stories circulate in the Amazon, however, that the robbery was a ruse, and that Brugger’s death was the result of an argument with Tatunca over royalties from “The Chronicle of Akakor.”

The suspicions do not stop there. Brazil’s federal police acknowledge that they are investigating the separate disappearances of an Austrian man and a woman from New Zealand, both of whom were last seen with Tatunca.

Tatunca denied involvement in the killings in statements to Brazilian authorities and a U.S. consular agent. As he told it, Reed and Wanner each ran away and hid in the jungle when he asked them to return with him to Barcelos. He said he put Heuser on a boat to Manaus, a city down the river, and never saw her again, just as he did with the Austrian and the woman from New Zealand.

But like the jungle butterflies whose brilliant patterns mimic bad-tasting varieties to throw off predators, Tatunca Nara has seemingly cloaked himself in deception and disguise.

According to West German authorities, Tatunca is really Guenther Hauck, a West German citizen born on Oct. 5, 1941, in Bavaria. The police have his birth certificate and other personal records. A police expert studied photographs of Hauck from his teens to early 20s, and of the man who calls himself Tatunca. The expert declared that they are the same person.

Police records show that Hauck was a sailor on a West German freighter in 1966 when he jumped ship in Venezuela. Arrested, he claimed to be an Indian. A psychiatrist diagnosed him as schizophrenic, and Hauck was returned to West Germany, where he was jailed for three months for failing to support his wife and two sons.

Three years later, Hauck sailed to Brazil and again jumped ship, the West German police say. This time he disappeared, and Tatunca Nara emerged. He married a Brazilian and they have two teen-age children. Last year, Hauck’s ex-wife traveled to Barcelos from West Germany and identified Tatunca as her former husband.

“His whole story is crazy,” insists Kurt Hartert, the detective heading the West German investigation. “This man we are talking about, who is suspected of having killed three people, is Guenther Hauck. There is no doubt about this.”

Hartert claims jurisdiction because Hauck is still a West German citizen, and West German law extends to its citizens anywhere in the world. But Brazilian authorities have refused to allow the West German investigators into the country, contending that Brazil is conducting its own inquiry.

The U.S. State Department has sent diplomatic notes to the Brazilians asking that the German investigators be allowed into the country. Edwin L. Beffel, the U.S. consul general in Brazil, recently went to the Foreign Ministry in Brasilia to reiterate the request. So far, the Brazilians have continued to resist.

Diplomatic niceties, however, have been no barrier to Sandy Reed’s struggle to discover what happened to her brother.

For years, Sandy Reed and her mother, Virginia, clung to the improbable belief that John was living with the Indians in the Amazon. Hadn’t his last letter said he was only a day or two from Akakor? Hadn’t the U.S. consular agent in Manaus sent them assurances that Tatunca was a “genuine Amazonian Indian” who was capable and responsible?

Even when warned by the State Department in early 1981 that John Reed could be in danger, his mother had said she did not want anyone to search for him. She felt he was following his plan to live with the Indians.

In early 1984, Sandy Reed was reading her local newspaper when she spotted a small story from Rio de Janeiro. It said a West German journalist had been killed during a robbery attempt. His name was Karl Brugger.

“I wondered if it was somehow connected to Johnny,” said Reed. “I was really worried. I thought of going to Brazil to try to find him, but I kept postponing it, hoping for some news from Johnny.”

Five years later came worse news. A West German adventurer told the Reeds that the West German police suspected Tatunca of killing three people in the Amazon, including John Reed. They wrote the police for details, and the reply brought another shock: Not only was Tatunca Nara a suspect in three homicides, he was actually a West German citizen.

The letter ended with a disheartening assessment: “The corpse of your son was never found, and there is little hope that the mortal remains might ever be discovered.”

Sandy Reed quit her sales job, scraped together what money she could and began arranging the long-delayed trip to South America from her home near San Francisco.

She had always admired her brother, who was two years older. He was not just a dreamer but a doer who had always followed his convictions. Now she would follow hers and find out what happened to him. To do that, she would have to find Tatunca Nara.

In June, 1989, she flew to Manaus, an isolated city of 1.2 million about 900 miles from the Atlantic Ocean in the heart of the Amazon. Farther up the Rio Negro, two days by boat and two hours by plane, was Barcelos, the home of Tatunca Nara.

At the turn of the century, Manaus was a boom town where rubber barons built colonial mansions overlooking the river. An opera house was erected out of stone and marble shipped from Italy in 1896; Caruso once sang there. Instant tycoons sent their soiled clothes to England for cleaning.

Today, the rubber boom is long gone and so is the prosperity. Manaus is clogged with pollution, begging children and crumbling concrete buildings. About 200 foreign-owned assembly plants, paying low wages and turning out goods from television sets to sunglasses, ring the city.

Sandy Reed spent three weeks there in 1989, badgering a Brazilian prosecutor about her brother’s disappearance and scouring the city for scraps of information about John and Tatunca Nara.

A friendly tour agent looked at John’s picture and thought she might have seen him on the outskirts of the city, dazed and wearing large black rubber boots. The prosecutor said Tatunca told him two miners had spotted someone fitting John’s description with an Indian tribe a few months earlier.

Before going to Manaus, Reed had arranged a meeting with James R. Fish, the part-time U.S. consular agent who had written several letters to her family. Fish did not show up for the meeting. So, Reed tracked him down in Fortaleza, a resort city on the Atlantic, flew there and confronted him in an exchange that she tape-recorded.

Fish described Tatunca delivering her brother’s final letters to his office in late 1980, claiming Reed had run away from him. Fish said he figured John had found “an interesting situation” in the jungle and had decided to stay.

Pressed about his assurances in a 1981 letter that Tatunca was a “genuine Amazonian Indian,” Fish said: “He is not an authentic Indian in the sense of being born with Indian blood in him. But he does all the things that Indians do. All the people in Manaus that you talk to say that his trip is the real thing.”

Back in Manaus, Sandy Reed was warned not to try to meet Tatunca. Barcelos was too remote, the sort of place where someone could be killed quietly and anonymously. She grew frightened and moved from cheap hotel to cheap hotel each night, always registering under a different name.

She decided not to confront Tatunca--at least not then, and not alone.

One story she heard during this period was more terrifying than all the others. A former Swissair pilot reportedly had gone into the jungle with Tatunca in 1981 and come upon a headless skeleton lying in a green nylon hammock. Beneath the hammock lay a hair brush and tooth brush. Tatunca reportedly had said that the bones, hammock and personal items were those of John Reed.

Sandy Reed flew to Zurich, where the ex-pilot, Ferdinand Schmid, repeated the story. He said Tatunca had tossed the bones into the river and given the hammock to an Indian boy. He gave Reed a photo of the boy holding the hammock.

A friend of Schmid’s, who had gone on a later trip with Tatunca, said the guide had told him that John Reed had been living with an Indian tribe when he ventured too close to a woman bathing in a river and was shot to death by her jealous husband.

From Zurich, Sandy Reed took a train to Wiesbaden, West Germany, and spent a long evening discussing the case with Kurt Hartert, the German detective. Hartert was sympathetic but uncertain about the chances of solving the mystery. There were no bodies, and the Brazilians were blocking his attempts to interrogate Tatunca.

“You can only come to the truth when you break Tatunca--when you are able to convince him that he must say he is Guenther Hauck,” Hartert said.

Reed refused to let go. Returning home to Northern California, she began cleaning houses for $12 an hour to earn money for a return trip to Brazil. At 36, she could have been building a career, but she needed to be able to resume her search at a moment’s notice.

She talked with Wolfgang Brog, a West German documentary producer who was gathering information about the disappearances for a television show. She flew to Munich and met with him. They arranged to rendezvous in Manaus to track down Tatunca.

Her second trip to the Amazon was planned for late last month. This time, Reed would go on to Barcelos. A Times reporter and Brog would go along.

“There are days when I don’t feel Johnny is alive,” said Reed as she packed for the trip. “The evidence that I’m collecting makes me think he’s not alive. I don’t know. Somewhere in my heart, oh . . . I guess I can’t know until I face Tatunca.”

On June 21, Sandy Reed arrived in Manaus and checked into a $20-a-night hotel on a noisy downtown street. She spent several days tracking down new information, doggedly scribbling in a small red notebook and tape-recording conversations.

One afternoon, after failing to find the local prosecutor in his office, she paid an unexpected visit to his home. Joao Bosco Sa Valente was polite enough, perhaps even a bit embarrassed, as he admitted that he had made no progress since their meeting a year ago.

“It’s only me doing this case,” Valente lamented, turning up the palms of both hands. “Nobody helps.”

Valente said his requests for assistance from the federal police had been ignored. He said he had documents showing that Tatunca once worked for the Brazilian army, and he speculated that the military might be protecting him.

“Very strange things happen around this case,” he said.

A few days later, the federal police said Valente had never asked for help. They showed Reed their own file on Tatunca Nara. She was stunned. Rather than the names of her brother, Wanner and Heuser, the file concerned two different people--an Austrian man and a woman from New Zealand--who had disappeared separately after saying that they were going into the jungle with Tatunca. Tatunca told the police that he put them on boats back to Manaus and never saw them again.

“We have no proof,” said a federal police officer in Brazil, who asked that his name not be used. “We never found any bodies and no eyewitnesses or anything. All we have is hypothesis.”

On Monday, July 2, a clerk at Reed’s hotel placed an anonymous call to the only telephone in Barcelos. Yes, Tatunca Nara was in town. He was at the Hotel Oasis, the three-room inn on the Rio Negro that he and his father-in-law had built years before.

Arrangements had to be made hurriedly. The small scheduled airline to Barcelos was flying up the next day, but no return was available until Thursday. Two nights in Tatunca’s territory, where he ran the only hotel, seemed a foolish risk.

A series of telephone calls and a substantial amount of cash secured the promise of a chartered airplane. It would be waiting at the Manaus airport the next morning.

Reed slept little that night, tossing restlessly in her bed. In the dark early morning, her hands were shaking as she cradled a cup of coffee. She stuffed a knapsack and the pockets of her bush jacket with a tape recorder, a small notebook, a red folder containing documents and, emblazoned with the words “Top Secret,” pictures of her brother and his last letters from the Amazon.

Before leaving the hotel room, she reached down and yanked the buckle free on her leather belt, exposing a lethal-looking, four-inch dagger. Slashing horizontally across the belly of an imaginary foe, she said: “This is how my cousin showed me to use it. It doesn’t even show up in an airport metal detector.”

The small twin-engine plane lifted off shortly after 10 a.m. and rose to 8,500 feet. The Rio Negro spread out below, half a mile wide in places, black water laced with strips of bright green jungle and dotted by tiny islands.

Reed had left her morning bravado on the ground. Replacing it was a mixture of fear, sadness and exhilaration as she approached the climax of her journey. She scanned her two-page list of questions for Tatunca, drawing a heavy line under the first one: “What happened to my brother?”

She leafed through her brother’s letters and extracted one found among Karl Brugger’s papers after his death. It was dated Nov. 24, 1980. John Reed had said that he had met Tatunca in Manaus that day and gone with him to Barcelos. They were about to set off for Akakor, and Reed was excited. But there was a note of doubt about Tatunca.

“Is he a liar or a prince?” he wrote to Brugger.

The plane bounced twice and settled onto the rough landing strip that had been chopped out of the jungle at Barcelos. It was almost noon, and the sun was hot. There was no breath of wind. The dense foliage pushed against the edges of the unshaded road leaving the airport.

Unsmiling children watched the athletic, auburn-haired woman walk through the town, occasionally whistling in an eerie, low monotone. Along the river bank, a girl of 6 or 7 bathed naked in the water beside a beached houseboat.

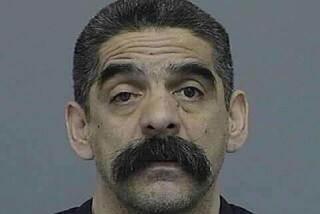

Suddenly, there was the Hotel Oasis, perched on a high bank above the Rio Negro. It was more a large home than a hotel. Just inside the wooden gate, watching the strangers approach, was Tatunca Nara. He wore only a pair of patterned shorts. A turtle was tattooed on his chest. His eyes and hair were brown, and he was deeply tanned. His features were sharp, more European than Indian, and he was lean and muscular.

Smiling warmly, he invited the visitors in and directed them to the shaded veranda overlooking the river. Reed and her companions sat at a small table and sipped Cokes in silence while Tatunca finished his lunch.

When Tatunca moved to the small table, Reed brought out the pictures of her brother and identified herself. A broad smile crossed Tatunca’s face as he shook her hand and asked, “Why didn’t you come years ago?”

“They told me you are a dangerous man,” Reed said.

She began to question him gently, retelling the stories that had circulated about those who had disappeared--her brother, Herbert Wanner, Christine Heuser.

“These stories are crazy,” said Tatunca. “It’s crazy. I have killed no one.”

He said that he had barely known John Reed. They had spent only two or three days together, heading up the Rio Negro and the Rio Padauari. Tatunca wanted to return to Barcelos, but Reed insisted on staying.

“I told him, ‘You don’t go in the jungle. You are crazy.’ But he wanted to see the Indians,” said Tatunca.

Reed shook her head in disbelief. Her brother’s letters indicated that he had spent at least 10 days with Tatunca and the guide had promised to show him Akakor.

What about Schmid, she asked--the Swiss who said Tatunca had shown him bones in a hammock and said they were her brother’s?

“It’s absurd,” Tatunca said. He insisted that the bones were from a wild pig he had killed some months before. And he said they were beneath the hammock, not in it. The hammock and other items, he said, were his. “I was just joking with him. I said only, ‘Maybe someone died here.’ ”

He told of two gold miners who had come out of the jungle about a year ago and described seeing a tall blond man living with the Indians. “Nobody knows who this blond guy is,” he said. “Maybe your brother is still alive.”

When Tatunca grew agitated or needed to explain something complicated, he abandoned English and Portuguese and launched into fast, fluent German. He said he had spent seven years in West Germany. But he denied that he was born and reared there, claiming that his birthplace was near the border of Peru and Brazil. Sure, he knew of Akakor. No, he had never promised to take anyone there.

The subject of Brugger’s book irritated him. Pointing both thumbs down, he denounced the book as “80% lies.” But when asked if he killed Brugger, he said, “I did not kill him--he was my blood brother.

“Why would I kill a man? For what? No reason. No reason.”

As the questioning wore on, Reed appeared to grow more incredulous. Tatunca’s story conflicted too sharply with her brother’s letters and with the stories she had heard from others around the world. If Tatunca were telling the truth, then her brother had lied. She could never accept that.

Finally, Reed could endure no more. She rose from her chair, fists clenched. Tatunca jumped up too.

Tears streaming down her face, Reed spoke each word clearly and deliberately: “Tatunca, you are a liar. I have no respect for you. I hate you. You killed my brother. You killed my brother.”

Tatunca winced under the blunt accusation and pleaded: “No, Miss Reed. What motive? What motive? Why would I kill your brother?”

“Because you’re crazy--and you will pay for my brother’s death,” Reed responded sharply.

She gathered up her papers and tape recorder and walked through the door and into the road without turning. Tatunca slumped into his chair and shook his head slowly.

The road back to the airport was as hot as a sauna. Reed ducked into a tiny grocery store and emerged with two large bottles of Antarctica beer and plastic cups tucked in her blue knapsack. At the empty terminal, she pried off a beer cap with a Swiss army knife.

“Now, I know my brother is dead,” she said calmly, as if some chasm of suffering and uncertainty had been bridged. “Tatunca lied to me about everything. It’s time to get this behind me. But Johnny would have been proud of me.”

A few minutes later, the plane lifted off, swept low over Barcelos and the Rio Negro and climbed into the sky. Dark clouds were visible in the west; the pilots were in a hurry to beat the storm.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.