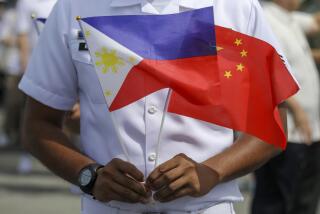

U.S. Aid to a Troubled Philippines Refocuses Debate on Military Presence : Bases: With U.S. image high in the wake of recent natural disasters and an attempted coup, negotiations may take on a different tone.

- Share via

MANILA — While U.S. and Philippine negotiators ready for another round of talks on America’s military presence here, at no other time in recent memory have U.S. military personnel played such a visible role in restoring calm to the troubled nation.

In the past year, Americans based at the largest U.S. military installation outside the United States have helped put down a coup attempt that almost toppled the Aquino government, launched dramatic rescue missions in the aftermath of the July 16 earthquake and played a vital role in typhoon-relief efforts.

Although U.S. officials strenuously avoid playing up these events, the past year has brought strong reminders of how dependent the Philippines has become on about 40,000 U.S. military representatives stationed at permanent installations at Clark Air Base, Subic Naval Base and four smaller facilities.

Vivid television pictures of U.S. servicemen pulling survivors from under the rubble at Baguio are sure to be etched in the minds of people here when the two countries resume negotiations for a new bases agreement later this month or early September. The current agreement allowing the U.S. military installations in the Philippines expires in September, 1991.

To some, the U.S. bargaining position never looked better.

“The earthquake definitely improved the climate for the negotiations,” said Philippine Rep. Jose de Venecia, a prominent member of the Joint Legislative-Executive Bases Committee. “This was a shining moment in America’s role in the Philippines.”

Media reports frequently speak of how the 400 U.S. servicemen from Clark were the first to arrive in the mountain resort city of Baguio with 55-bed mobile hospitals, supplies and equipment. In comparison, the Philippine military arrived late and appeared disorganized, Western diplomats said.

A surprising number of letters to the editor in local newspapers and columns have drawn a link between the U.S. participation in earthquake relief efforts and the bases debate. Coming on the eve of the most important phase of bases negotiations, in an eerie sort of way the disaster came at a time when Uncle Sam needed a way to prove his usefulness to ordinary Filipinos.

“The majority approved of our assistance in the coup attempt and they are glad we did what we did. The same holds true for the earthquake,” said a U.S. official.

Whether or not the same feeling is echoed throughout typhoon-ravaged Manila--where spray-painted signs with such slogans as “No to U.S. Bases” compete for space with gaudy Filipino movie billboards--is uncertain. This is still a land where people see U.S. conspiracy theories behind most events, such as the recent withdrawal of the U.S. Peace Corps--seen as a ploy by Washington to exert pressure on Manila ahead of the negotiations.

Until now, the debate over retention of U.S. bases has been wrapped up in an emotional web of arguments ranging from the threat the bases pose to Philippine sovereignty to how much the U.S. should pay for using some of the most coveted pieces of real estate in the country.

But analysts predict that the highly visible U.S. involvement in putting down the December coup and the quick U.S. response to the earthquake could influence the undecided members of the Philippine negotiating team--lead by Foreign Secretary Raul Manglapus--to drop its hard-line posturing.

National pride will heavily influence thinking on the Philippine side of the negotiating table. In a recent interview, President Corazon Aquino, who has studiously avoided spelling out her position on the issue, said the presence of the bases has stalled her country’s efforts to achieve full sovereignty. “It’s a matter of our national sovereignty and territorial integrity,” she said. “In any country where there are foreign bases on native soil it does create a problem.”

Last week, Aquino raised hopes of U.S. officials, saying she wanted the talks finished within five months.

When the two sides sit down together to hammer out an agreement, the Philippine side is in no position to dictate terms. Filipinos may have already overplayed their hand in earlier negotiations by demanding exorbitant rent for base lands and placing unrealistic demands on negotiators. The Philippines wants at least $360 million for use of the two installations. (The Bush Administration has responded with a request to Congress of $220 million in 1990, but is not expected to come up with more than $160 million.)

What’s more, before coming to the negotiating table earlier this year, Philippine officials failed to acknowledge the potential huge economic dislocation of removing the bases, which employ 78,000 Filipino workers. One aide to Aquino described the embarassing Philippine approach as “stick’em-up-guy diplomacy.” In recent months, Aquino’s government seems to be clinging to power and defending itself against charges of inaptitude. Rumors of coup attempts, frequent power outages, water shortages, charges of corruption and a frightening economic decline have combined to transform Malacanang Palace into a crisis-management center. Last week, troops in the Philippines were put on full alert following rumors of a fresh coup attempt.

Washington may not have to look hard for convincing arguments to bargain down the compensation fee for the bases. More than ever, Manila may not be willing to risk the loss of large amounts of critically needed American foreign aid.

“There is a feeling at the moment that the U.S. should not be given carte blanche for their own purposes in the Philippines,” said De Venecia.

De Venecia is the author of a popular proposal that would transfer Philippine bases now situated on valuable land in Manila to either Clark or Subic, under a generous agreement giving the United States until the year 2000 to withdraw.

The plan, approved by the Philippine Bases Council in February, also calls for Manila’s congested Ninoy Aquino International Airport to be moved to Clark, about 60 miles north of Manila. Both moves could generate billions of dollars for the cash-strapped government and free up tracts of land for redevelopment.

“This is the best possible option for the Philippine government,” De Venecia said. “It is designed to usher in a new era of friendly relations between the Philippines and the United States.”

If the Philippines adopted such a strategy, it would shift the emphasis from the money factor to planning a withdrawal that would minimize disruption to the economy and prevent acute political embarrassment to the government. A phased-out withdrawal also means America would not be placed in the uncomfortable position of saying an abrupt goodby to a long-time ally.

Once the two sides reach an agreement, it could still be scuttled by lawmakers in the United States. A bizarre provision in the Philippine constitution stipulates that the bases agreement must be ratified not only by the Philippine Senate but by the U.S. Senate as well. U.S. officials say they much prefer an executive agreement, but the Philippine feeling is that the Senate’s imprint would give it the full force of an international treaty.

But this should not cause undue worry to U.S. negotiators. Said one senior official close to Aquino, “The United States always gets what it wants around here. There is no doubt that there will continue to be some U.S. presence after 1991.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.