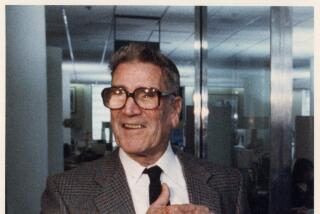

They Came From Near and Far to Mourn the Passing of a Most Uncommon Man

- Share via

PINE PRAIRIE, La. — He was no mover or shaker. He never held public office and didn’t have a lot of money. But 400 people made their way to the deep woods of central Louisiana to attend the wake of the man they all knew as Mr. Hugh.

They came to pay their respects to Hugh McDaniel, vegetable farmer and story teller, who died at age 73.

News of the wake had been broadcast throughout the day on KVPI Radio in Ville Platte, in both French and English since this part of the country represents the marriage bed of the Catholic-Cajun and Protestant cultures.

Illiterates mingled with university professors. Welfare recipients chatted easily with a couple of oil millionaires. All had been charmed by Hugh McDaniel, farmer and storyteller.

Bo Goodman, for example. He doesn’t own a car. He hitched a ride.

And William Leece, owner of an oil field service company, a business in a frenzy due to the crisis in Iraq. He locked his office for the day to attend.

Maude King came. She lives so far back in the woods that even in the 1960s some residents didn’t have electricity.

The wake lasted 24 hours, with the kitchen of the Friendship Baptist Church working around the clock concocting steamy gumbo, coffee thick enough to float a spoon and enough deserts to make a fat man weep.

Plates of Cajun sausage-- boudin-- were complemented by the Protestants’ traditional chicken and dumplings.

As a drizzling rain fell constantly this autumn day, inside the church one pew was filled with the Naquin family, cousins of McDaniel, who conversed and prayed in French.

A cousin from another branch of the family leaned over the pew to speak to the Naquins. “How’re y’all,” he drawled.

Many sat all night in the church.

The later services were conducted by four ministers, including two Baptists, a Church of Christ lay preacher and a Catholic priest. Organized religion is casual here.

Hugh McDaniel symbolized that casualness. The son of a French-speaking, Catholic mother, he went to the Baptist church as a youngster simply because that church was closest to the farm. Those were the days of mud roads and few autos. And time away from the farm could mean a lost crop and a bare cupboard.

And typical of the 1920s, he spoke mostly French until he went to school, where teachers whipped those who didn’t speak English. Such attitudes nearly killed the Cajun culture, which was revived in the 1960s. Now, French is taught in elementary school.

Hugh McDaniel was not typical in other ways, this man who grew vegetables and fruit on a few acres along Dun Beef Creek just north of Pine Prairie.

He was the kind of man that most of us, as youngsters, want to emulate, but wind up in middle-age realizing with some self-pity that we never made it.

Mr. Hugh gloried in his God, his family, his fellow man and the soil--in that order.

People were naturally drawn to the warmth of a man who never met a stranger.

Over decades, word-of-mouth sent the message through several parishes. There was a man in the woods growing anything that could sprout. They came to buy. Discovering that he was a storyteller, customers sat under the pecan trees and listened. They left as friends.

He made the headlines of a local newspaper when he grafted a domestic peach tree with a wild tree, developing a new strain of the fruit.

County agents and agriculture professors from the University of Southwestern Louisiana heard of his delicious peaches. They listened to accounts of how he grew crops that couldn’t be sustained in that part of the country where the frost came early.

The experts traveled to the farm to see for themselves, to see if he could grow satsuma oranges this far north. Could he really grow kiwis? That couldn’t be done in this climate. Surely, he couldn’t produce Vidalia onions, which were grown successfully only in a few Georgia counties.

Ah, but he did all that. The professors also sat under the trees, sipping iced tea and listening to Mr. Hugh’s stories.

He had little desire for material possessions but dutifully worked the oil fields at times for the money that would give his four children the benefit of college educations.

The farming wouldn’t sustain those expenses because Mr. Hugh wouldn’t charge enough. On top of that, he gave away as much as he sold, traveling the roads with food for the sick and the jobless.

The millionaire Leece met the farmer in the oil fields, totally disarmed by a grimy, oil-spattered employee who treated the owner like a fellow employee, wanting to chat during breaks.

Leece found that he missed those chats and was drawn to the farm once Mr. Hugh’s college funding duties were over.

With time on his hands, Mr. Hugh contributed columns to the Ville Platte Gazette, sometimes featuring Jean Pierre with a Cajun dialect. A simple man’s view of the world, a bit of local history, a humorous account of a personal experience.

So, he is gone, taking with him the well-chronicled stories of his wonder dogs, Revlon and Rich. We’ll hear no more of friend, Calabas, or jokes about the “ol’ woman,” his cherished wife, Eudole, now 70. Spring won’t bring another column of God’s grace at planting time.

But, not to mourn. Mr. Hugh would be the first to say that mankind is like the soil in a way, sprouting other storytellers. Maybe they are out there now. Maybe his columns have inspired other simple folk to take up the pen.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.