In the Political Theatrics of Thatcher’s Jazzy London : Britain: Britain was far different when Thatcher took office in 1979, the current flash and dazzle of London typify how she revved up the society.

- Share via

LONDON — It is, as Margaret Thatcher said ruefully the day she decided to resign as Britain’s prime minister, a funny old world. Less than a week later, there she was, looking pleased as punch, all smiles, saying she was “thrilled” with the result of the election for leader of Britain’s Conservative Party--who automatically became Britain’s new prime minister.

Well she might be. Thatcher watchers have known since 1987 that John Major, who now moves into 10 Downing St., has long been her anointed heir. When all is said and done, the last few remarkable weeks in Britain add up to this: Thatcher has handed over the baton of leadership to exactly the person she always wanted to succeed her, but has done so a couple of years earlier than she would have wished. There are worse ways to go.

Why was she so keen on Major? Principally, because he comes from a similar background to hers: the respectable lower-middle class, though in his case not from the provinces but from London--in Britain, an important distinction. He is a self-made man of the kind she likes best: He left school at 16, and worked on construction sites before he became a clerk in the City of London. He has the same kind of commitment to market economics she has, and the same kind of belief that hard work and determination never hurt anybody. He is friendly and approachable: The British would say there is no “side” to him.

Beyond that, he is a bit of an enigma. He is said to have a fine political nose, but I can exclusively reveal to readers of The Times that last year I won 10 off him by betting that two Cabinet ministers would not survive a government reshuffle. He was adamant they would. They didn’t.

Major is thought to be less opposed to European integration than Thatcher was, but if he is, he is keeping his true feelings to himself. Just last week, he dismissed a single European currency as an economic folly--not what they think in Brussels at all. When foreign secretary for three months, in 1989, he looked--to the uncharitable--out of his depth, and--to the kindly--a man still mastering his brief. Those close to him say that he is a man of deeply felt convictions; but they have not been made obvious to the rest of us.

Not that much of this mattered last week. The real story of Major’s elevation to the premiership is what it says about modern Britain, and how it has emerged from its most amazing decade of the century. Consider the performance of Douglas Hurd, one of the two defeated candidates. An excellent foreign secretary, a man with a fine record in government, intelligent and cultured, he spent the campaign trying to live down that he had gone to Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge. This, remember, was an election for the leader of the Conservative Party; repeat, the Conservative Party.

Neither Hurd nor Michael Heseltine, the other contender, could match Major’s “classlessness.” (He went to a local high school, hated it and never attended university.) Hugo Young, Thatcher’s biographer, put his finger on the pulse, as usual, when he said the election’s central question was: “Who would you rather drink a pint with?” When conviviality in a bar counts for more in high British politics than attendance at Eton, you know something wonderful has happened.

This was Thatcher’s doing. Though a bundle of contradictions--she married a wealthy man and awarded hereditary peerages--she is, at heart, a meritocrat. She had spent years being patronized for her sex; in her last interview as prime minister she said, “If a woman is strong, she is strident. If a man is strong, gosh, he’s a good guy.”

Those memories meant that she could not endorse any form of preferment--such as birth, or schooling--that did not turn on individual accomplishment. She left behind a society that was more meritocratic than the one she found in 1979. It is far from perfect--if it had been, the men in gray suits who took such delight in stabbing a jumped-up woman in the back would have stayed their hand. But, ye gods, it is a better place in which to be clever and able than it was. Perhaps, the most touching epitaph to Thatcher came from Julie Burchill, a rebellious young punk-rock journalist in 1979, and now best-selling author 11 years later. Our Julie, when asked for her reaction to the prime minister’s resignation, said the Thatcher years “made me bloody rich. I feel like someone’s banged me over the head with a hammer.”

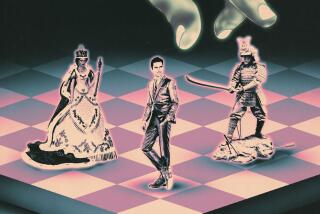

Now there was the authentic voice of 1980s London. The 1980s, for the capital, were a golden age, a time when anything was possible--something like the 1920s must have been in New York. London, under Thatcher, became jagged, edgy, entrepreneurial, international, sleazy, rich and fun. Its drink of choice was champagne; its hot businesses were music, media and fashion.

I thought it was wonderful. And back here for three days for the first time in a year, I felt how marvelous a backdrop to the drama London provided. It is precisely because London is not just a government town that it provides unexpected seasoning to political dishes. Everyone was talking about the race, everyone glued to the television, devouring newspapers. In the trendy Groucho Club, black-clad women ad-executives smoked and drank bubbly, turning the leadership options this way and that. When the result was announced, a porter at my tube stop rushed to chalk it on a blackboard; the late editions of the papers were snatched from news-sellers hands.

The contrast with Washington’s narcolepsy could not have been more clear. Just think: This whole business was started a few weeks ago by Sir Geoffrey Howe’s resignation speech to the House of Commons. Can you imagine any speech, by any member of Congress, having such a devastating effect? Can you imagine Washington men appearing unprompted, unrehearsed, unadvised, in front of the cameras as often as our three lads did? Can you imagine Washingtonians using bubbly to lubricate a political argument, when most don’t know which end of a champagne bottle goes “pop”?

There are those who say we British spend far too much time on partisan politics, far too much time in our clubby, unexportable political institutions like the House of Commons, far too little time being serious about such worthy matters as a European currency. All true. But--oh my!--for those who love politics, the intrigue, the theater, the lies and cheating, the sheer vulgar thrill of it all, the old town was the place to be last week.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.