A Prized Fighter : Still Scrappy at 90, Nobel Laureate Linus Pauling Is Gaining in His Battle on Behalf of Vitamin C

- Share via

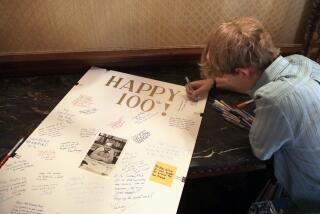

PALO ALTO — “The last time I counted,” says Linus Pauling, his blue eyes sparkling beneath a charcoal-colored beret, “I have seven birthday parties to go to.”

With that, the aging guru shuffles off to graciously accept the first of many birthday cakes and equally sugary tributes to his longevity, this one from his staff at the Linus Pauling Institute of Science and Medicine.

On the occasion of his 90th birthday, one can hardly blame his family, friends and colleagues for staging one celebration after another.

And you can’t fault Pauling for relishing every minute. Tonight, 800 guests will fete him in San Francisco. That will be followed by a daylong symposium and dinner celebration Thursday (his birthday) at Caltech, where he spent the most distinguished part of his career, from 1922 to 1963.

Pauling doesn’t appear too concerned that he is still often described as a Nobel laureate and a quack in the same breath. The man who revolutionized chemistry with his work on the nature of the chemical bond continues to invite--even welcome--scrutiny of his long-held belief that Vitamin C helps prevent cancer and other illnesses. The winner of Nobel prizes for chemistry and peace remains at war with the science Establishment.

Pauling, though, is winning some battles. Last September, the National Cancer Institute held a symposium on Vitamin C and cancer during which a majority of the presenters supported Pauling’s views on the vitamin’s preventive powers.

Moreover, the privately funded institute Pauling founded in 1973--while he was still performing some research many scientists hold in dubious regard--recently landed some respectable projects. Those include a Department of Energy grant to work on one aspect of the Human Genome project, a national effort to decode our entire genetic structure.

“My wife used to say I’m just stubborn,” Pauling says, referring to Ava Helen Pauling, who died in 1981. “But I have great confidence in human rationality. And I fight for my ideas.”

Pauling defies categorization, a fact reflected by the mix of visitors to the institute. “We get everyone from top-notch scientists to incredible kooks and cranks,” says Richard Willoughby, a veteran scientist and institute facilities manager.

Colleagues say Pauling is consumed with writing papers to advance his theories on Vitamin C and a half-dozen other scientific problems in such diverse disciplines as X-ray crystallography, theoretical physics and quantum mechanics.

He divides his time between his coastal ranch in the Santa Lucia Mountains of Big Sur--where he lives alone and cooks his own meals--and the institute, an unpretentious structure 160 miles away, near Stanford University.

Pauling moves gracefully and speaks articulately. He attributes his longevity to good genes, a relatively stress-free life and Vitamin C.

“There were stressful periods: when my passport was taken up (in 1952, because of anti-war protests) and I couldn’t travel to scientific meetings, and when I was being accused--not only once--of being a communist,” he says. “But the main causes of stress I think I managed to avoid. My wife and I were married for just under 59 years; we got along well with one another. Our children turned out well.”

Pauling was in his mid-60s when he began taking Vitamin C.

“I’m sure that during the last 26 years, my good health is a result of the large amounts of the vitamins that I took,” Pauling says.

Each day he puts 18 grams of pure crystalline ascorbic acid powder--the equivalent of 260 glasses of orange juice and 300 times the Recommended Daily Allowance--into juice or water, then drinks it without wincing.

Pauling’s determination long ago elevated him to a place among American scientists that is likely to remain unequaled. He is the only person ever to earn two unshared Nobel prizes.

His work on the nature of the chemical bond, for which he won his first prize in 1954, has been the platform for many major advancements on the chemical structure of complex substances. So exalted was Pauling’s reputation in the 1940s and ‘50s that many people thought he could solve almost any scientific problem he set his mind to.

In his memoirs, geneticist James Watson tells of his great fear that Pauling would beat him to the discovery of the structure of DNA. (In fact, Watson and Francis Crick proposed the correct double-helix structure while Pauling, his passport revoked and unable to attend scientific meetings, was working in solitude on a triple-helix model.)

Pauling credits his achievements to hard work and intuition.

“I knew what the problems were, and I knew how to attack them,” he says. “There were many people who knew what the problems were but didn’t know what to do about solving them.”

But, he maintains, the answers never came easily.

Pauling says his most significant achievement also brought the most sadness. In most interviews, he makes a point of retelling the events surrounding the announcement of his 1962 Nobel Peace Prize. That prize rewarded his efforts to limit nuclear-warhead testing.

“I was still at Caltech,” he recalls. “I saw in the Los Angeles Times a statement that (Caltech President Dr. Lee) Dubridge had made that it was ‘really remarkable that a person should get two Nobel prizes, but there is much difference of opinion about the value of the (peace) work that Professor Pauling has been doing.’ So I thought, well, the time has come. I’ll quit.”

Shortly thereafter, Pauling resigned.

Pauling continues to protest war and nuclear-weapons testing. He recently spent $18,000 for two newspaper advertisements protesting the Persian Gulf War.

The protests are simply in line with his respect for health and longevity, Pauling says: “If I’m concerned about getting control of cancer or heart disease so people won’t suffer so much and will have longer and healthier lives, I have to be concerned also about the possibility of their being killed or injured in war.”

He rarely travels now, but Pauling will attend a reunion of Nobel laureates in December. He was invited to a gathering of chemistry prizewinners in Stockholm and a simultaneous ceremony for peace prizewinners in Oslo.

Pauling says he’ll be in Oslo.

“The peace prize is the one I value the most because receiving it means to me that working for world peace is respectable.”

The Nobel prizes stand in contrast to the way much of Pauling’s recent work has been received.

Most mainstream scientists still react with horror to his claims that Vitamin C in high doses can prevent and help cure colds, lengthen the lives of AIDS patients, and prevent cancer and heart disease.

But Pauling is persistent--as Sam Broder, director of the National Cancer Institute, has learned.

A year ago, Pauling harassed his way into a meeting at Broder’s Bethesda, Md., office to discuss Vitamin C and cancer prevention.

“He said he could spare an hour, but he listened to me for 2 1/2 hours,” Pauling says. “And during the last half hour, he finally became interested. I told him some of what he thought were facts about Vitamin C just were not true.”

In addition to authorizing the September symposium on Vitamin C, Broder also appointed a committee of researchers to judge Pauling’s anecdotal evidence on cancer patients who have reportedly done well taking high doses of Vitamin C.

Pauling was clearly buoyed by the meeting, but the committee has yet to release its findings.

Although some studies show Vitamin C may have value in cancer prevention, little evidence supports Pauling’s views that high doses could be effective in the treatment of cancer, AIDS or colds.

“There is so much skepticism among doctors about Vitamin C that I think some of the members of the committee may be rather biased,” he says.

To Dr. Victor Herbert, no one is biased: Pauling is simply wrong.

Herbert, the author of “The Mount Sinai School of Medicine Complete Book of Nutrition” is a vociferous Pauling critic: “Linus is a guru of nonsense. He is a believer rather than a scientist in this area. There is no value in a megadose, and there is no study showing that people who take megadoses of Vitamin C live longer than people who don’t take megadoses. Linus just believes what he wants to believe. And when the facts differ from his misperceptions, he just believes his misperceptions.”

Pauling seems puzzled by the resistance to studying Vitamin C and the viciousness of the attacks.

“When I published my book ‘Vitamin C and the Common Cold’ in 1970, I thought everybody would be happy, including the doctors who would be able to tell a patient: ‘Here is something we know that can help.’ Instead they started attacking me.

“I was astonished. I thought, well, if a medical discovery is made, experience shows it usually takes about 10 years for the clinicians to accept it. So all I have to do is wait 10 years. I can publish some papers perhaps, and in 10 years they will have accepted it. But here now it has been 21 years since my book was published.”

One small but significant development is that the major health and nutrition organizations now recommend that people increase their intake of fruits and vegetables to help prevent cancer. But Pauling can’t understand the medical Establishment’s rejection of vitamin supplements and its resistance to studies that would establish whether there is an optimal dose of Vitamin C that enhances health.

A growing number of nutritionists and health experts, however, suggest that supplements are acceptable when nutrients can’t be obtained naturally from the diet.

“I think the evidence is extremely compelling on Vitamin C having a role in cancer prevention,” says Patricia Hausman, a licensed nutritionist and author who is an expert on vitamin supplements.

But Pauling earns far less support for some more-recent theories that ascorbic acid might help prevent heart disease and improve AIDS patients’ health. Last September, Pauling announced that Vitamin C cripples the AIDS virus in the test tube.

Says critic Herbert: “Linus is right: Vitamin C kills the AIDS virus in the test tube. But you can (urinate) in a test tube and kill it. Where you can’t kill it is in a living cell in a living body.”

Indeed, some members of the scientific community long have been irritated by Pauling’s proclivity for far-reaching conclusions based on very preliminary findings.

“It’s not doing his scientific reputation any good. He’s not following the scientific methods,” says Jim Enstrom, an associate research professor at the UCLA School of Public Health who has co-written papers with Pauling on Vitamin C. “The method is not to go out and make pronouncements before the study is done.”

But Ahmed H. Zewail, the Linus Pauling Professor of Chemical Physics at Caltech, calls Pauling a misunderstood genius.

“If there are two things about Pauling that are unique, it’s the intuitiveness and creative thinking he takes on to solve a problem.

“As a chemist, he has to be one of the greatest scientists of the 20th Century,” Zewail says. “Whether or not he is right on Vitamin C--and it needs experimentation and proof--he certainly has the vision to see ahead.”