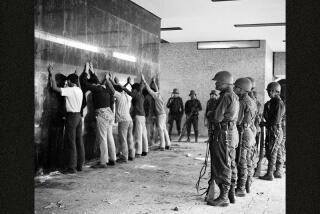

For ‘Burned Ones,’ Military Still Calls the Shots in Chile : Despite civilian rule, armed forces courts retain jurisdiction over personnel who are accused of abusing the rights of citizens.

- Share via

SANTIAGO, Chile — Carmen Gloria Quintana charged in 1986 that soldiers doused her and a friend with gasoline and set them afire, a case that became a symbol of political repression under the former regime of Gen. Augusto Pinochet.

Today, for many Chileans, it symbolizes continuing military impunity from significant legal sanctions for past human rights abuses.

Court-martial proceedings in the Quintana case ended in January, and the only officer facing charges, Capt. Pedro Fernandez Dittus, received a suspended sentence of 300 days.

“This is an inconsistent ruling,” Quintana said in a recent interview. “It is based only on military testimony. It doesn’t take into account overwhelming evidence against the military men.”

Quintana, a university psychology student, has appealed to the civilian Supreme Court. Whatever the court’s ultimate decision, the case already illustrates an important Chilean reality: Although an elected civilian government has been in power for a year, the system of justice for military offenses has changed little.

Military courts retain jurisdiction over charges of human rights violations by armed forces personnel. And military courts are noted for dismissing, stalling and otherwise burying human rights cases.

“The processes go on forever,” commented one foreign diplomat.

The case of the quemados --”burned ones”--is unusual because it reached the final stage of judgment in military court, from which an appeal can be taken to the Supreme Court. Even so, the process took 4 1/2 years.

Few other cases involving the military and human rights abuses are expected to get that far. For one thing, the Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld a decree of the former military government, granting amnesty for violations occurring between 1973 and 1978.

A series of legal reforms recently approved by Congress will give civilian courts more jurisdiction over charges against civilians for violating laws involving state security, terrorism and weapons-control. But there is no provision for transferring human rights cases against military personnel to the civilian courts.

Quintana and her friend, Rodrigo Rojas, were burned July 2, 1986, during an anti-Pinochet demonstration near a poor Santiago neighborhood where Quintana lives with her parents. Demonstrators were burning tires and throwing homemade gasoline bombs.

Fernandez Dittus, then a lieutenant, was leading an army patrol trying to help break up the demonstration. The army says that after the lieutenant detained Rojas and Quintana, she kicked a self-igniting Molotov cocktail, which set fire to a spilled container of gasoline.

But a police investigative report indicated that the pair suffered burns that were too extensive to have been caused by a kicked firebomb and spilled fuel.

Fernandez Dittus said he carried the pair away in an army pickup truck, then left them on a nearby street when he was summoned by radio to another disturbance. He said that they did not seem to be badly burned.

Quintana, then 18, says she and Rojas were dumped unconscious in the dirt on the outskirts of Santiago, 15 miles from the demonstration.

Rojas, 19, died four days later in a hospital. Quintana has since undergone 50 operations on scars that covered more than 60% of her body.

While Pinochet was still president, the U.S. State Department repeatedly expressed concern about the quemados case, asking that it be resolved by due judicial process. Diplomats said the United States took a special interest because Rojas was a U.S. resident.

Early in January, the highest military court upheld Fernandez Dittus’ 300-day suspended sentence on a charge roughly equivalent to homicidal negligence, based on his failure to seek medical care for Rojas. But the court martial dismissed a negligence charge in relation to Quintana’s injuries.

Investigation transcripts show that military witnesses changed their versions of important facts in the case. Officers admitted lying to cover up army involvement early in the investigation.

“In this tangle of lies, does it seem possible to believe the military version that the fire started because one of the victims broke a Molotov cocktail?” asked Chilean journalist Patricia Verdugo in a recent magazine article. She said, “Everything indicates the truth of the version” that the victims were intentionally soaked with gasoline and burned.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.