Indian city flourished, then faded quietly away : Lost civilization had jewelry, trade, maybe even smog.

- Share via

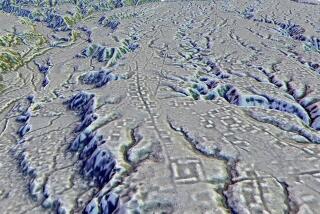

COLLINSVILLE, Ill. — They are an incongruous sight, gigantic earthen mounds rising like pyramids from the level Mississippi River flood plain.

For perhaps eight centuries, long before the arrival of Europeans, they stood at the heart of a teeming city, an American Indian metropolis unsurpassed in size on the continent until 1800, when the population of Philadelphia reached 30,000.

“It was sort of a cross between New York, Washington and the Vatican,” said Bill Iseminger, an archeologist on the staff of the Cahokia Mounds Interpretive Center located at the site, about seven miles east of St. Louis. “It was a combination of a trade, political and religious center.”

Today there is little trace of this lost civilization. Unlike the Egyptians, the Incas or the Aztecs, who built their pyramids in stone, the Indians who lived here built structures made of earth.

Although archeologists believe the mounds served the same functions as towering structures in other civilizations--to elevate important people or religious buildings above the rest of the city and as burial places--no dramatic temples or pyramids were left behind for the ages.

Their houses and religious buildings were made of thatch. Even the gigantic circular sun calendars--called “Woodhenge” by the interpretive center planners who have reconstructed one of them at the site--were made of perishable materials.

Like the people who built these structures, much of the evidence of their existence has vanished from sight. No one even knows what the inhabitants called themselves, although they are believed to have been related to the Mississippians, who also inhabited this area, because of similarities in traditions. The name Cahokia is from a later group of Indians who inhabited central and northern Illinois.

By the 1500s, long before the French arrived here in the late 1600s, the inhabitants of the city had vanished.

Artifacts found at the site indicate that they had a wide trade network. Shells and pottery indicate that the city’s inhabitants had contact with Indians living in coastal areas and in what later became the Southern United States. The Indians living here are believed to have traded surplus corn or to have redistributed shell beads or finished jewelry.

The first archeological digs were conducted in the 1920s, but it was the declaration of the location as a World Heritage Site in 1982 by the United Nations (placing it on a par with the Pyramids of Egypt, the Great Wall of China, Rome and the Taj Mahal) that caused the state of Illinois to commit $8.2 million to develop an elaborate exhibit and interpretive center.

Estimates of the size of the ancient city range from 5,000 to 50,000 inhabitants. The Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, which operates the interpretive center, uses the figure 20,000.

Some archeologists, citing the small number of grave sites that has been found, dispute the higher size estimates. They contend that the area was more of a commercial center than a permanent city and that large numbers of people gathered here perhaps once a year for ceremonies.

But the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency contends that large numbers of people were necessary to move the estimated 50 million cubic feet of earth used to construct the mounds, 65 of which are preserved within the boundaries of the historic site. In addition, a gigantic stockade was built around the center of the sprawling city, which contained a huge plaza.

Iseminger points out that less than 1% of the community has been excavated. “We haven’t really located and don’t actually plan to excavate cemeteries at this point,” he said, citing opposition to disturbing Indian burial grounds. “Often you learn more about a society by digging in the trash pits than you do by digging in cemeteries anyway.

“Every place we’ve dug here we’ve found evidence of continuous occupation and continuous use of the land,” he said.

The state owns 2,200 acres. The city was believed to have been 4,000 acres. Satellite communities are believed to have existed on the other side of the Mississippi River, where downtown St. Louis sits today.

A population decline is thought to have occurred gradually, perhaps due to climatic changes that hampered agriculture or by a combination of failing agriculture, political upheaval and disease caused by pollution.

“It was the largest concentration of people on the continent north of Mexico, so there had to be an impact on the environment. They probably had smog here,” Iseminger said. “With all the fires burning all the time there must’ve been a pall of smoke over the valley here.”

The decline is believed to have started around the year 1200. By 1500, they were gone.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.