Ex-Parliament Leader Denies Role in Coup

- Share via

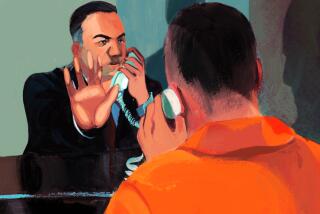

MOSCOW — Anatoly I. Lukyanov stepped nervously to the rostrum of the Supreme Soviet on Wednesday. The Soviets’ national legislature used to be his domain, but now he was there, like a prisoner in the dock, to answer accusations that he conspired in last week’s abortive coup d’etat --and betrayed his oldest and closest friend, Soviet President Mikhail S. Gorbachev.

Lukyanov, former chairman of the Supreme Soviet, had been the “ideologist” of the Kremlin coup, Russian Federation President Boris N. Yeltsin charged. He was its “gray cardinal,” others said. A statement he issued on the day of the coup had been used to justify the attempted takeover.

Gorbachev himself said that Lukyanov, perhaps his closest political confidant and a friend from their days at law school in the 1950s, let him down badly in not opposing the coup--if he did not, in fact, join the plotters. On Monday, Lukyanov was suspended from his office pending investigation of his role during the coup.

Lukyanov, 61, on Wednesday denied all the allegations, and, with a plea to the lawmakers for vision and soberness in their deliberations, brought the packed chamber to a hush.

“I have this duty to look you in the eye and tell you that, contrary to the charges here, I have never been a conspirator, much less the spiritual leader of the conspiracy,” he said.

Where he had failed, Lukyanov acknowledged, was in not moving fast enough to convene the Supreme Soviet and to use its authority against the coup. He said he hesitated out of fear of bloodshed and of the legislature’s possible dissolution by the junta that seized power.

“There was a loss of orientation, confusion, a lack of knowledge of the true state of affairs--yes,” Lukyanov admitted. “But treason there was not and could not be. If the president has not been convinced of this after all the crises between (Gorbachev’s assumption of power in) 1985 and now, I am truly sorry.”

Although far from a courtroom cross-examination by a tough prosecutor, this was the first public interrogation of a suspected conspirator and a preview of the treason trials that will follow for the ringleaders. And the questions put to Lukyanov will soon be put to many others in the government and in political life: What did they know, what did they do, why did they not resist?

“Frankly speaking, I would not like to be in Lukyanov’s place,” said Maj. Vladimir P. Zolotukhin, a journalist on a military newspaper and a deputy from Uzbekistan in Central Asia. “From one side, he’s a man of the old system when the center was the head of everything, and he has nostalgia for this. From the other, he is Gorbachev’s friend, or says he is. . . .

“Lukyanov is a great master of the games played by the apparat (the political establishment) and he has been a witness to many intrigues. I think he was sure that the Supreme Soviet would approve the state of emergency, and he himself was a supporter of such measures. But as a master of intrigues and the apparat game, he did everything in such a way that he can now say what he wishes, and everything is truth.”

Lukyanov said that he was not even in Moscow when the coup began on Sunday, Aug. 18, and that when he learned of it that evening, Gorbachev was already the plotters’ prisoner. Asked to cooperate, he had refused, he said.

“My first words to the conspirators were that their undertaking was an irresponsible adventure, that it was a conspiracy of the doomed,” he recounted. “Their doomed conspiracy, nonetheless, had the potential to cause a civil war and an upsurge of anti-communism, to give momentum to the disintegration of the Soviet Union and to inflict heavy damage on our foreign policy.”

His political views may be judged conservative, Lukyanov said, but he wanted to preserve the Soviet Union and its socialist orientation while reforming the economy and developing a federal political system.

He had been timid and failed where the daring and boldness of “people power” had succeeded in turning back the coup. Lukyanov argued that the paramount needs were avoiding bloodshed and preserving the new institutions of Soviet democracy.

“If I were a newcomer who had never heard or seen him before, I might have believed him,” said Vitaly I. Goldansky, a leading Soviet scientist and a deputy. “But knowing all the background history of manipulating the Parliament and having met and spoken with him . . . I was not satisfied with his explanations.”

It had been Lukyanov, deputies recalled, who had encouraged Prime Minister Valentin S. Pavlov’s bid in June for emergency powers, a move strongly supported by the Defense and Interior ministers and the KGB chief. All four men were among the conspiracy’s ringleaders, and their first statements harked back to the Supreme Soviet debate two months earlier.

Gorbachev, too, has not accepted Lukyanov’s explanations despite a friendship that goes back to the days when Lukyanov was the leader of the Communist Youth League at Moscow State University and Gorbachev was his deputy.

As the coup collapsed, Lukyanov flew to the Crimea, where Gorbachev had been held at his vacation home, to discuss the situation. Gorbachev listened but returned with the delegation sent by Russian Federation President Boris N. Yeltsin.

“To convene the Supreme Soviet, only a few hours were necessary,” said Konstantin D. Lubenchenko, deputy chairman of the body’s committee on legislation. “A quorum was necessary for approval of the criminal junta, but there was no need for a quorum to make a statement or start discussion on the legality of this junta. And this would have had moral importance.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.