Chileans Cheer, Mourn on Anniversary of Army Coup : South America: Crowds gather at Pinochet’s home to mark his takeover. ‘This is a sad date,’ Aylwin says.

- Share via

SANTIAGO, Chile — A year and a half after the return of democracy, Chile is troubled by reminders of harsh and turbulent times under military rule.

Old animosities flared up when some Chileans celebrated and others mourned on the 18th anniversary of the bloody coup on Sept. 11, 1973, that brought the armed forces to power. The date became a national holiday under the military regime, but President Patricio Aylwin said it is no cause for celebration.

“This is a sad date,” Aylwin said while visiting Easter Island, a Chilean possession in the South Pacific.

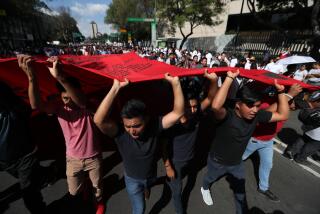

That morning in Santiago, a cheering crowd gathered outside the home of Gen. Augusto Pinochet, the coup leader and former dictator who remains as commander of the army. Later, thousands of other Chileans marched in mourning to the tomb of Salvador Allende, the president who reportedly committed suicide while his office was under attack during fighting that toppled his Marxist-Leninist administration.

The opposing views reflected deep and persistent divisions over the coup and the military regime. Pinochet supporters insist that the armed forces did what was necessary to save Chile from communism, while Allende sympathizers remain bitter over what they portray as fascist brutality.

President Aylwin, a centrist Christian Democrat, lamented that these divisions make it difficult to “reconcile the Chilean family.” The nature of Chile’s revived democracy, in which the dictatorship’s legacy is as clear and present as Pinochet himself, makes it probable that reconciliation will come only gradually as the divisions play themselves out in democratic give and take.

Among the unresolved issues left over from the dictatorship are atonement for official excesses and Pinochet’s continuing status as army commander.

Some Pinochet opponents seized a new opportunity to demand his resignation the other day after he made a blunt remark about unidentified bodies buried during the bloody aftermath of the 1973 coup. In compliance with a court order, more than 100 bodies were being exhumed from Santiago’s general cemetery when a reporter asked Pinochet to comment on a report that at least one grave contained more than one body.

“What a big savings,” Pinochet said, triggering a barrage of public indignation. The government called his statement cruel.

In a television interview later, Pinochet acknowledged that his remark may have been tactless. But he said he has no plans to resign.

The constitution, written under the military government, permits Pinochet to stay on as army commander until 1997. Many analysts have said that, with the army under his control, the general can exert strong pressure to prevent the trial of officers for human rights abuses.

One of the most notorious human rights cases was the assassination of Orlando Letelier, a former Cabinet minister in Allende’s government and prominent Pinochet critic. A car bomb in Washington, D.C., killed Letelier and his American assistant on Sept. 21, 1976.

The United States tried unsuccessfully to extradite retired Gen. Manuel Contreras, director of secret police under the military regime, and another former officer on charges of ordering the assassination. In Chile, the case lay dormant in military courts until a justice of the civilian Supreme Court reopened it recently.

At the instigation of Contreras’ lawyer, a military court is now reclaiming jurisdiction. It is assumed that the case will be filed away again by the military court if the Supreme Court honors the claim. If not, one of Pinochet’s most trusted former lieutenants could be put on trial.

Either way, the Letelier case seems sure to continue stirring Chile’s troubling memories and old animosities.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.