Scientists Work to Harness Bacteria’s Taste for Toxins

- Share via

For 4 billion years, the Earth’s creatures have been evolving genes to help them eat what they find around them.

Given a few millennia, bacteria and fungi will mutate until they can eat almost anything organic. But some of the toxic chemicals man has made--including PCBs, TCEs, DDT and dioxin--haven’t been on the planet long enough for microbes to evolve the ability to digest them.

With environmental problems pressing, however, modern man is attempting to hasten the process.

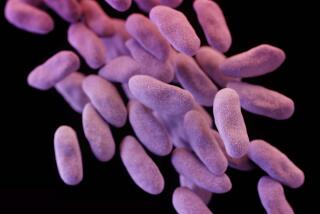

At universities and environmental cleanup companies, the race is on to commercialize strains of “superbugs,” natural or genetically manipulated microbes that can degrade toxic chemicals that were once considered indestructible.

To the winner may fall millions of dollars of environmental cleanup contracts and a head start on a technology that proponents say could revolutionize the way industry handles waste.

If bacteria can break down toxic chemicals in a Superfund dump, for example, why not use them to detoxify waste coming out of the factory before it becomes a problem? One biotechnology company, Envirogen Inc. in Lawrenceville, N.J., is already working on such applications.

While there are sophisticated techniques for removing carcinogenic, caustic or flammable waste from soil or water, the technology for actually getting rid of the stuff remains primitive, scientists say.

Hazardous waste can be buried in special landfills where, it is hoped, it will remain inert indefinitely. Or it can be burned, which environmentalists say only transfers the problems into air pollution toxic ash.

But bioremediation--using bacteria to break down waste into harmless chemicals--offers the alluring promise of ridding the planet of some hazardous gunk for good.

A few of the waste-busting bacterial processes are on the cusp of commercialization. Others will take years of research and may never pan out. But among the recent scientific advances:

* A number of strains of naturally occurring bacteria has been shown in laboratory tests to break down TCE, or trichloroethylene, a suspected carcinogen and a major polluter of ground water. Ecova Corp. of Redmond, Wash., says it has begun a pilot test of one such bug in a polluted aquifer in California, and Envirogen is about to begin testing another natural bug in New Jersey.

* Envirogen also has a patent on a genetically engineered bacteria that eats TCE. The company will soon ask the Environmental Protection Agency for approval to test its bug’s digestive prowess inside a specially designed, sealed tank called a bioreactor. The EPA has expressed deep reservations about allowing the use of genetically altered bacteria, but Envirogen hopes data from a carefully controlled test may change the agency’s mind.

* Dennis Focht of UC Riverside has isolated two separate strains of natural bugs that degrade simple types of PCBs (polychlorinated biphenols). One bug has the genetic right stuff to transform simple PCBs into a byproduct, while the second bug breaks the byproduct down into carbon dioxide, salt and water. Focht is trying to mate the two strains to produce hybrid offspring that could do the entire job.

* In New York, General Electric Co. scientists are using river bacteria to clear PCBs from the sediment in the Hudson River. The experiment involves two kinds of bugs--one that requires oxygen and one that doesn’t. Scientists are also adding oxygen and different types of nutrients to try to speed the natural process of decay.

* The U.S. Geological Survey has discovered several different bacteria that will wolf down uranium compounds in water, concentrating the radioactive stuff into solid clumps that can then be removed. Microbiologist Derek R. Lovley thinks that the bugs might also work on other radioactive metals such as plutonium and technetium and is trying to arrange a field test at a polluted uranium mine or nuclear weapons production site.

But many questions remain.

Can bacteria that degrade stubborn compounds in the laboratory do as well in the field, where they face mixed waste, harsh weather and competing organisms?

Should scientists stick to using bacteria that evolve in nature, or can they literally “build” a better bug through genetic engineering? And should such artificial creatures be released into the environment?

So far, the EPA has not been asked to approve any genetically altered bacteria for use in breaking down toxic waste. In general, bacteria used in bioremediation projects die off when their food supply is depleted, but the EPA and others have expressed concern about the possibility that artificial microbes could reproduce and out-compete naturally occuring bugs.

The burden will be on the bug-handlers to prove that their microbes are safe.

“Before we would approve something for release into the environment, we’d have to have fairly extensive data, and quite often that data is not available,” said Erich Bretthauer, EPA assistant administrator for research and development.

Moreover, many scientists and regulators are not sure that genetic manipulation of bacteria is really necessary. They say natural strains of bacteria will prove hardier, safer and more versatile.

“When you take genetically engineered bugs out of the lab, it’s kind of like taking young children out of a country club school and throwing them into a back alley-type hostile environment,” said Andrew D. Paterson, managing director of the Research Institute for the Management of Technology in Pasadena.

Some environmentalists are particularly skeptical.

“The idea that we can have a few genetic-engineered bacteria and solve our toxic waste problem is ridiculous for the most part,” said Rebecca J. Goldburg, a biologist with the Environmental Defense Fund in New York.

In the end, the answer may depend on how formidable the chemical that is to be degraded, and how intrepid the waste-eating bug.

Trichloroethylene, or TCE, for example, is a simple chemical that has been used since World War II to degrease metal, strip paint from airplanes and, more recently, to clean electronic circuit boards. A handy product, it has also been used as a dry-cleaning solvent, in liquid correction fluid and even as an anesthetic.

Unhappily, the EPA now classifies TCE as a “priority pollutant,” a toxic substance and a possible carcinogen. It is considered a major threat to ground water in the San Gabriel Valley and in Northern California’s Silicon Valley, and it has polluted aerospace sites and military air bases across the nation.

There are a number of natural bacteria that can break down TCE, said Mary E. Lidstrom, professor of applied microbiology at Caltech in Pasadena. Lidstrom studies a strain that grows on methane but happens to be able to make the enzyme to degrade TCE.

“It’s a biochemical accident that they use TCE,” she said. “They are not doing it on purpose.”

But there’s a hitch. Although the bacteria can degrade even minute quantities of TCE--and thus could meet strict EPA standards--high concentrations of the stuff poisons them, Lidstrom said. Another strain of TCE-munching bugs can handle high doses but loses interest before the waste is completely gone, she said.

“There are ways to combine those two traits, but you’d have to do it in the laboratory,” she said. Such a bug would then have to pass regulatory muster before it could be used.

Lidstrom believes that scientists will eventually find strains of naturally occuring bacteria to break down TCE, but garden-variety bugs will probably prove no match for complex compounds such as PCBs.

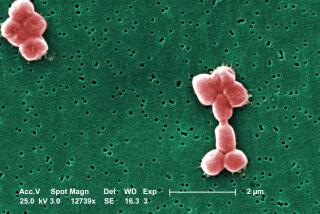

Envirogen’s TCE-eating bug has a more exotic pedigree. It hails from the Thousand Oaks labs of Amgen Inc., the biotechnology company better known for its pioneering work in pharmaceuticals. Amgen managed to isolate the genes that degrade TCE from a common soil bacteria and inserted them into E. coli, the common bacterium that lives in human intestines.

Amgen patented the new bug, and then swapped it to Envirogen last year in exchange for an undisclosed amount of Envirogen stock, Envirogen Vice President Ron Unterman said. Now, Envirogen has re-engineered the gene so it can produce large quantities of the TCE-degrading enzyme cheaply and so that it is easier to control, he said.

Unterman said the genetically altered bug may prove much more cost-effective than natural strains. And, as the product of two benign bacterial strains whose chemistry is extremely well understood, the bug is very safe, he said.

What Bacteria Can and Can’t Do

Pollutants That Can Be Degraded

Bacteria can degrade these compounds with relative ease:

Petroleum products: gasoline, diesel, fuel oil

Hazardous crude oil components: benzene, toluene, xylene, naphthalene

Some polynuclear aromatics: benzo(a)pyrene, a carcinogen found in coal tar, oil and charcoal.

Some pesticides: malathion

Coal compounds: phenols and cyanide in coal tars and coke waste.

Some industrial solvents: acetone.

Many ethers

Simple alcohols such as methanol and other ground-water contaminants including methylethylketone.

Ethylene glycol, an ingredient in antifreeze, often found at airports.

Partially Degradable Pollutants

These are chemicals that are difficult to degrade, or wastes that are so mixed and variable that they degrade at different rates and may leave some toxic chemicals behind.

TCE (trichloroethylene): a major threat to ground water; it has been degraded in pilot tests but never in full-scale cleanups.

PCE (perchloroethylene): a dry-cleaning solvent; it degrades to TCE when no oxygen is present.

Wood preservatives, including pentachlorophenol, and other ingredients in coal tar: can be degraded but only under carefully controlled conditions.

PCBs and dioxins: have been degraded in the laboratory but not in the field.

Arsenic, chromium and selenium: Bacteria have been used to stabilize these poisonous compounds in pilot tests, but the technology is still being developed.

Experimental

Heavy metals are not biodegradable, but bacteria can concentrate them into forms that make them more easily disposable.

Uranium: A strain of iron-eating bacteria can be used to extract the low-level radioactive waste from water.

Mercury: Poisonous as an element and as a salt, but scientists are experimenting with using bacteria to stabilize it in a safer form.

DDT: The now-banned pesticide can be degraded, with difficulty, in test tubes.

Source: John T. Wilson, senior research microbiologist,

Environmental Protection Agency.