Plug in the Sky : Researchers Offer Unorthodox Plan to Heal a Hole in the Ozone Layer

- Share via

Hoping to prod the world’s scientific community into addressing ozone depletion in a more organized and rigorous fashion, UCLA and UC Irvine researchers have offered a highly unorthodox method for repairing the ozone hole that appears over the Antarctic each October.

Based on their findings with computer models, they suggest today in the journal Science that a fleet of hundreds of large airplanes could be used to inject 50,000 tons of the hydrocarbons ethane and propane into the Antarctic stratosphere each year.

They predict that the hydrocarbons would neutralize the ozone-destroying chlorine molecules produced from chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), widely used by industry as refrigerants and in insulating foams, and thereby prevent the ozone hole from forming.

“We’re certainly not proposing this,” cautioned UCI geoscientist Ralph Cicerone. “We are serious about thinking about these things, but we aren’t serious about going out and doing them yet.”

Cicerone and his colleagues concede that their proposal faces formidable legal and ethical questions and may even have unforeseen side effects. In one scenario, for example, too little ethane or propane would actually enlarge the ozone hole. But they remain undaunted.

Cicerone said he and UCLA atmospheric scientist Ralph Turco, along with Scott Elliott of UCI, came up with the proposal because they had spent a lot of time “behind the scenes” batting down “dangerous and dumb ideas” about curing the ozone problem.

“I don’t like the idea of engineering the environment,” he said. But such ideas “are coming up more and more, and we shouldn’t ignore them any longer. We thought these global ideas should be considered very carefully and made part of the normal scientific process.”

Other researchers applauded them for putting forth a carefully thought-out proposal, even if they did not consider it practical. “I think the scientific community has some responsibility to deal with the wild and crazy ideas and do an honest evaluation,” said atmospheric chemist Michael J. Prather of the NASA-Goddard Research Institute in New York City. “Scientists think about such things, but there’s been no real forum yet for discussing or evaluating large-scale solutions.”

“This is a starting point to see whether there are strategies to minimize ozone depletion,” said UCI atmospheric chemist F. Sherwood Rowland, who first suggested the danger from CFCs. Rowland, who is not an author of the paper, noted: “There have been many such suggestions all along, and most have been total nonsense. This one is starting to put it on a scientific basis of how one might approach the problem.”

In the stratosphere--the layer of the atmosphere between nine and 20 miles above the Earth’s surface--ozone shields the planet from the damaging effects of the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. CFCs rise to the stratosphere, where they are broken apart by sunlight. Chlorine molecules liberated in this fashion destroy ozone, allowing ultraviolet radiation to reach the Earth’s surface, where it damages plants and animals, including humans.

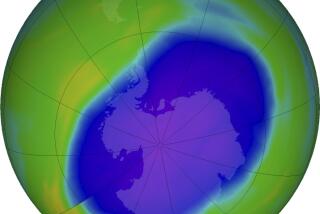

The most serious problem arises over the Antarctic. During the long, sunless austral winter, corresponding to summer in the Northern Hemisphere, CFCs accumulate in supercooled clouds. When sunlight returns in October, it frees chlorine, producing a sudden burst of activity that destroys more than 50% of the ozone layer. The destruction can persist until February, when winds finally restore normal air circulation patterns.

The United States and other nations have signed the 1987 Montreal Protocol, which has since been amended to require an end to CFC production by the year 2000. In fact, industry has been phasing them out even faster.

Nonetheless, Rowland said, “Because of time delays, we can expect depletion to get worse for another couple of decades. If it gets much worse, we will find that it is worthwhile to consider whether there are ways to reduce the damage that is being caused.”

After studying atmospheric models, they concluded that either propane (which is used in camping stoves and lights) or ethane is harmless in itself and could tie up enough chlorine to stop significant ozone depletion.

Even if the idea survives scientific scrutiny, Cicerone added, “we have to begin to worry whose right it is to make such decisions, whose interests will be preserved. . . .” The answer to that question is not obvious, he said.