UCLA Plans Relatively Quick Course on Einstein : Education: The two-day extension program is geared for those who are curious about the still-popular scientist and his remarkable theories.

- Share via

In his day he was as famous as Elvis. In fact, he’s still as famous as Elvis.

In a culture that makes heroes of rock stars, hockey players, almost anything but scientists, Albert Einstein is unique in that he is universally recognized and widely admired by people who couldn’t tell you what E equals mc squared means if it would save them from drowning.

Today, more than 35 years after his death, his image is still a favorite on collegiate T-shirts worldwide--a look of eternal perplexity beneath a mushroom cloud of disheveled hair, clearly a man who has given up hope of ever seeing his fountain pen again. More remarkably, his science endures. Discoveries made by the Hubble telescope and other new technologies have given his once-futuristic theories even more credibility than they had in his lifetime.

Not bad for a kid who babbled until he was 4 and who worked in a patent office as a young man because he couldn’t get a job as a teacher.

Einstein, the man and his legacy, is the subject of a two-day course this weekend offered by UCLA Extension. Extensively illustrated, the program is “designed for the person who isn’t quite sure whether a quasar is an astronomical phenomenon or a television set,” according to writer-astronomer Andrew Fraknoi. Executive director of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific in San Francisco and editor of its Mercury magazine, Fraknoi will co-teach the course with writer-physicist Alan Friedman, who is also director of the New York Hall of Science.

Fraknoi said he has been fascinated with Einstein since he was 15. As a bookish young boy from Hungary, Fraknoi was drawn both to Einstein’s ideas and his persona. Einstein’s message to the youngster was “it was OK to be a bright, scientific type, that he was beloved even though he was slightly nerdy, which I felt I was.”

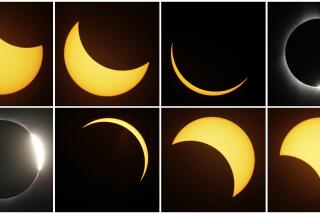

As Fraknoi tells audiences, modern science journalism virtually began with coverage of the German-Jewish genius. Einstein published his landmark paper, “The Foundations of General Relativity Theory,” in 1916. Three years later, a group of British scientists went to Africa to test one of Einstein’s contentions--that gravity could bend or deform space--during a total eclipse of the sun. The British expedition verified that the gravity of the sun had bent beams of starlight visible during the eclipse, and the British press trumpeted: “German Savant’s New Theory of Space and Time Proved by British Expedition.”

A media darling was born.

Fraknoi speculates that journalists liked Einstein for the simplest of reasons. “He was a good story,” Fraknoi said. “He was an absent-minded professor. He had the weird hair. He was always able to give the good quotes. He was a refugee from the Nazis in Germany. There was the weirdness of what he did. All were good stories. And, in his case, the nice thing was he deserved to be famous.”

Einstein left his native Germany in 1933 to become the most famous resident of Princeton, N.J. But local audiences are always fascinated to learn that Einstein had lived in Pasadena for several years before settling permanently in the United States.

A visiting professor at Caltech, Einstein divided his time in the Southland between scientific activities and Jewish ones, including campaigning for the creation of a Jewish homeland (he was eventually offered the presidency of the new state of Israel but turned it down). According to Westsider William Kramer, associate editor of Western States Jewish History magazine, the arrival of so distinguished an individual was a boost for Southern California’s image. “It was one of those events that erased some of the backwoods character that Los Angeles had.”

While living here, Einstein once sat down with Charlie Chaplin and lamented the loss of privacy that comes with fame. And Einstein played his violin in a Pasadena synagogue. “It was the one place he could practice without bothering anybody,” Kramer said.

Fraknoi and his colleague plan to demystify some of Einstein’s basic scientific concepts, including the theory of relativity. “Everybody thinks, ‘I’m no Einstein. I can’t understand it.’ ” Not true, Fraknoi insists.

The men also hope to dispel the myth that the great man was responsible for shoving the world into the nuclear age. Fraknoi said that Einstein had little or nothing to do with building the atomic bomb.

Fraknoi’s is a user-friendly approach to science that incorporates visual and aural aids as well as demonstrations. As a science educator, he said he is appalled at the state of science teaching in elementary and secondary schools.

“For a country that’s such a leader in science and technology, we do an absolutely shameful, shameful job of educating our youngsters, not just youngsters who are going to be scientists but people who are going to have to vote on issues such as what to do about the ozone hole.”

Fraknoi said his experience has been that children love science when they are exposed to it at an early age.