National Agenda : Embassy Bombing Ignites Political Debate : * Critics say Argentina’s pro-Israel, pro-U.S. stance invites such attacks. They blame President Menem.

- Share via

BUENOS AIRES — A couple of days after a devastating car bomb blew up the Israeli Embassy in Buenos Aires, President Carlos Saul Menem remarked: “We are the recipients of a terrorist act that, of course, Argentina has nothing to do with.”

Menem’s reading seemed to be that this sample of Mideast savagery had been transposed willy-nilly halfway around the world and arbitrarily visited upon an innocent Argentine nation.

In the anguished aftermath of the bloody bombing, however, some Latin critics have contended that Menem indirectly opened his country to such an attack by giving a pro-Israel, pro-United States tilt to his foreign policy.

Argentina, they note, was the only Latin American country to send warships to the Persian Gulf in response to Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait. In 1991, Menem became the first Argentine president to visit Israel. Then Argentina, which abstained when the United Nations voted in 1975 to equate Zionism with racism, co-sponsored last year’s successful U.N. campaign to overturn that resolution.

Thus, in the critics’ view, it’s not surprising that having ventured perilously close to the Mideast maelstrom, Argentina on March 17 got sucked in.

Other analysts speculate that perhaps because such an attack was so unexpected in Argentina, terrorists chose the embassy here simply as a “target of opportunity.” Also, the country has the second-largest Jewish community in the Western Hemisphere, following the United States, with an estimated 300,000 members. If those were decisive elements, Menem’s foreign policy might have had little bearing on the incident.

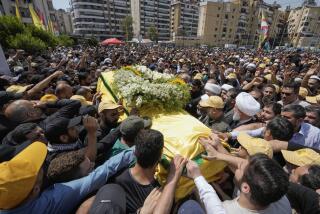

The pro-Iranian terrorist group Islamic Jihad, which has claimed responsibility for the bombing, said only that it was a suicide attack carried out by an Argentine convert to Islam in retribution for Israel’s assassination of Sheik Abbas Moussawi and his family in Lebanon. Moussawi was the reputed head of the radical Hezbollah, or Party of God, organization.

While the true reason Buenos Aires was the site of the bombing may remain clouded, the attack has clearly pushed questions of foreign policy noticeably higher on Argentina’s national agenda.

And those questions can be summarized in a way that might also be pertinent in other Latin American countries: Is it in the national interest to get involved in such volatile international problems? Or is it better to steer clear and leave such matters to the world powers and countries directly involved?

Menem has pursued a much more active Argentine role in international affairs after decades in which the country kept a relatively low global profile. That stance was reinforced by Argentina’s remote location in the southern reaches of the Western Hemisphere, by decades of economic and political instability, by episodes of harsh military rule, and by the 1982 war between Argentina and Britain over the Falkland Islands.

But Menem wants Argentina to join the First World of developed nations. And he sees good relations with other industrialized nations and with the international financial community as aiding that goal.

While Menem’s foreign policy has not been blatantly provocative, neither has it been designed to project low-profile neutrality. One of the president’s recent moves has been to pull Argentina out of the Nonaligned Movement, the 100-member organization of mostly Third World nations.

Menem has cultivated a close relationship with President Bush and the United States, Israel’s most important ally. When Bush visited Argentina in December, 1990, Menem remarked that the two have a “a very loyal, very sincere friendship.” Argentine nationalists, including dissident members of Menem’s Peronist Party, have criticized his stance as being so pro-United States as to be submissive.

Guido di Tella, Menem’s foreign minister, argued a few days after the embassy bombing that the incident had nothing to do with Argentina taking sides. “The attack came because Argentina has international presence,” he said. “It’s not a matter of having entered the First World but rather the world.”

At the time Argentina was debating Menem’s decision to send warships to the Persian Gulf in 1990, some critics were already warning that the move risked reprisals. The newspaper Pagina 12, for example, said then that Menem was “unnecessarily importing the problem of terrorism.”

Since the explosion at the Israeli Embassy, the same publication has run a series of columns critical of Menem’s foreign policy.

“Geopolitical alignment alongside the United States carries the certain presumed risk of importing alien conflicts,” wrote academic analyst Claudio Lozano in a guest column. “The relationship between the irrational measure of sending troops to the Gulf and the tragic recent episode is hard to miss.”

Bernardo Neustadt, Argentina’s most popular broadcast commentator, said the bomb would not have exploded in Argentina “if we had not said ‘so long’ to the Third World.”

While the Islamic Jihad responsibility claim has raised fears among some here that Muslim terrorists may be setting up shop in the country, no further evidence of such a move has emerged. Argentines of Arab origin, estimated to number more than a million (and including the Roman Catholic Menem), have always lived in harmony with Argentine Jews.

Still, what if bitterness over events such as the embassy bombing should polarize the two communities? The question has begun to worry some observers.

Ruben Beraja, president of the Delegation of Jewish-Argentine Assns., predicts the opposite. He has said that the “demential ferocity” of the bombers awakened “an extraordinary current of fraternal solidarity among all Argentines.”

Menem has asked for help from anti-terrorist experts in Israel’s Mossad, the American CIA and other foreign intelligence agencies to help track down the “beasts.” At the same rally, Menem said the terrorist attack will be a “kind of binding factor” between Argentina and Israel. “ . . . Starting with this act, the relations between Argentina and Israel will be more fluid, closer. They will galvanize,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.