COLUMN ONE : Why Do You Act That Way? : Research suggests that genes have about as much to do with it as the way you were raised. Studies of twins are producing insights into the shaping of behavior and personality.

- Share via

Barbara Parker was 36 when she met her genetic double. Returning home from the chiropractor one afternoon, she found a neighbor at her door. Remember you told me you were adopted and an only child? the neighbor asked. Well, your identical twin is in my living room.

There she was--Parker’s unknown, unimagined twin. Separated from her at birth, Parker had never dreamed the woman existed. But there, unmistakably, were Parker’s cheekbones, smile, curly brown hair--even, the neighbor gasped, Parker’s gestures and her laugh.

“The instant I saw her, I believed yes, she was my twin,” said Parker, a 45-year-old landscape designer and mother of two living in Canyon Country. “But shock became disbelief. I began grilling her: Who was our mother? When is our birthday?”

Since that afternoon, Parker and Ann Blandin have discovered even more startling things--not just physical, but emotional and intellectual similarities, patterns of likeness and difference that may help researchers unravel the role of genes in human behavior.

Both women are gregarious, emotional and perfectionists. One aspired to be a beautician, the other became one. Yet Blandin considers herself more critical, more emotional, thinner-skinned. She is more religious--a source of conflict between them.

Which traits are traceable to nature--the identical genes the women have shared since the fertilized egg from which they sprang split apart? Which come from nurture--the widely different circumstances under which they grew up?

And which force--heredity or environment--accounts for more?

“It’s back and forth, up and down,” mused Blandin, who has served as a guinea pig with Parker for the past nine years in a study that attempts to answer some of those questions. “It’s not exactly 50-50, but it’s a tossup.”

One of the most complex aspects of a human being is his or her behavior, long believed to be shaped primarily by upbringing. Now, research suggests that genes are more important than once thought in areas such as intelligence, temperament--even attitudes.

The most striking findings come from studies of identical twins, comparing twins reared apart to twins reared together. In numerous areas of personality, interests and views, researchers say twins reared apart end up at least as similar as those reared together.

The explanation, they believe, lies in the twins’ genes. Which is not to suggest there is a gene for gregariousness, perfectionism or becoming a beautician. Rather, a person’s genetic makeup may incline them toward certain people, ideas, jobs or ways of life.

The practical implications of such findings could be profound, experts say, in areas such as child-rearing, teaching and psychotherapy. In general, they should cultivate a deeper understanding of the innate quality of differences between people.

“Our data suggest that the differences between people in personality, intelligence, et cetera are fundamental and real,” said Thomas J. Bouchard Jr. of the University of Minnesota. “Therapists, teachers and people in the helping professions have to take that into account.

“They can’t just think, ‘I’m going to make X different or Y different,’ ” he added. “They have to say, ‘Given the characteristics of this person, what’s the best way to respect those and deal with the problem the person has?’ ”

Such theories are not universally accepted. The idea that genes shape ability, for example, is especially touchy. It seems to run counter to democratic dogma--that people are created equal and, given equal opportunities, each has a shot at success.

For that reason, critics say the findings will be misconstrued. Propensities will be mistaken for predestination, they fear. If genes influence, say, reading ability, people will think it can’t be improved. And if it can’t, why spend money to to help the shortchanged?

Skeptics have also challenged the tools used in behavioral genetics. They say researchers have used such crude measures of environment that they end up underestimating the impact of upbringing and overstating the effects of genes.

What’s more, critics say the research cannot show cause and effect. All it shows are associations between genes and behavior. With little hard evidence, critics fear, the field is giving new life to old notions of biological determinism.

Defenders counter, however, that genetic influence is not immutable: Genes confer tendencies, nothing more. They say factors such as family appear to play at least as important a part in behavior. And they are exploring both, albeit at an early stage.

“Our ignorance is so huge,” said John Loehlin, a professor of psychology at the University of Texas at Austin. “What we have are findings that suggest that genes are important. We have very little information as to how they actually work.”

The nature-nurture debate is among the hottest in the social and behavioral sciences. But for much of the 20th Century, nature has been eclipsed by the behaviorist notion that, loosely put, people could be conditioned to do almost anything.

Psychologist John B. Watson, for example, believed that by controlling the environment, he could elicit from a child almost any response. B. F. Skinner went on to show how the use of reinforcement--through rewards or withholding rewards--could shape, or modify, behavior.

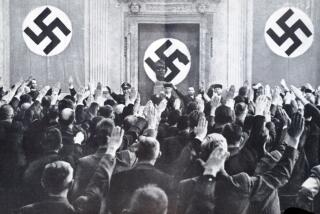

Another blow to behavioral genetics came from Nazi experiments in selective breeding. Talk of genes and intelligence became taboo. UC Berkeley psychologist Arthur Jensen rekindled the controversy in 1969 by suggesting that genes explain racial differences in IQ scores.

Adoption studies had begun to suggest genes played a part in schizophrenia. Those findings, along with the rise of molecular biology, helped reopen the issue of biological factors in behavior.

“We are in the age of genetics,” Joseph Campos, director of the Institute of Human Development at UC Berkeley, said in a recent interview. “Every week you will read about some major advance in molecular genetics. . . . People are more modest in their environmentalism.”

One of the primary tools of behavioral genetics is the study of twins and adoptive siblings. If genes influence a trait, the studies assume, then pairs who are more genetically similar should be more alike than less genetically similar pairs.

Identical twins, who share all their genes, should be more similar in that trait than first-degree relatives, such as sisters, who share about 50% of their genes. First-degree relatives, in turn, should be more similar than unrelated, adoptive siblings.

As Pennsylvania State University psychologist Robert Plomin puts it, the power of genes can be seen in the similarities between relatives raised apart, and the power of environment can be seen in the similarities between unrelated siblings raised in the same home.

“The fundamental goal is the same goal that most psychologists have--to understand the etiology of human behavior,” said Bouchard, who heads a large study of twins reared apart. “How does it come about? What are the major sources of influence? How do things work?”

Take Parker and Blandin, identical twins with very different childhoods. Their pregnant mother had arranged for the adoption of one baby. When two arrived unexpectedly, the second had no one to care for her. So the obstetrician took Ann home to his wife.

Blandin says she grew up “an oddball”--a skinny brunette in the midst of three statuesque, blond siblings. She felt she had to compete for attention. Her sisters grew up glamorous and career-oriented, as Blandin tells it, and she became a homemaker.

Blandin says she “sensed an awkwardness” in the family as a child. But she did not learn of her adoption until she was 15. A boyfriend, whose mother knew the story, blurted it out during a fight. To Blandin, it seemed to explain a lot.

Her sister’s childhood was not simple either. Parker’s adoptive parents separated when she was 1. When her mother died suddenly of leukemia nine years later, her longtime baby-sitter became her guardian. She was then raised as a well-loved, only child.

Those differences in upbringing may help explain some of the sisters’ perceived differences--for example, Blandin finds Parker more confident, less conscious of shortcomings. But all in all, Parker and Blandin see each other as more alike than not.

The most extensively studied trait in behavioral genetics is IQ--the subject of more than 100 twin, adoption and family studies. Together, the studies suggest that from 30% to 70% of the IQ variance between people is associated with genes, researchers say.

Take identical twins raised together: They share IQ scores as similar as those of the same person tested twice. The scores of twins raised apart are only slightly less similar, while those of unrelated siblings raised together often differ widely.

Specific mental skills, such as reasoning and verbal comprehension, show slightly less genetic influence than IQ, Plomin said. Reading disability appears to be influenced by genes, while creativity seems to be subject to little genetic influence.

As for personality, researchers have studied numerous qualities ranging from emotionality and sociability to sensation-seeking and anomie. Many personality traits show at least moderate genetic influence, researchers say.

Two of the most heritable appear to be extroversion and neuroticism--broad headings that subsume other, more specific traits. Extroversion, for example, encompasses sociability and liveliness; neuroticism includes moodiness, anxiousness and irritability.

Traits closely tied to intelligence also seem heritable, said Sandra Scarr, a professor of psychology at the University of Virginia. She found that authoritarian attitudes appeared heritable, perhaps because they are closely related to intelligence.

“People who are more authoritarian have lower IQ scores,” she said, based on studies that measured authoritarianism with a standard psychological test. “So, to the extent that intelligence is heritable, so is authoritarianism.”

“We don’t usually think of attitudes in that way . . . as so closely related to intelligence,” said Scarr, who found similar links between IQ and attitudes toward child-rearing. “We think of them as things we learn from our parents.”

Bouchard has found that traditionalism, a kind of conservatism and inclination to follow rules, appears strongly influenced by genes. Yet other attitudes and beliefs, including religiosity and some political views, appear subject to little genetic influence.

Much interest has focused recently on sexual orientation and homosexuality. While some researchers have linked homosexuality to brain structure, it is unclear whether those differences might be genetic or acquired in the womb, infancy or childhood.

A few researchers have claimed to find specific genes linked to manic-depressive disorder and schizophrenia over the past five years. But in the first case, the researchers later withdrew the conclusion; in the second, others have failed to replicate the finding.

“I think everybody accepts that there is a tremendous role of genes,” said Dr. David E. Comings, director of medical genetics at the City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte. “The controversy is about what is the mechanism of inheritance (and) what the role of genes is.”

No one in the field suggests that single genes direct specific behaviors. Indeed, no major genes have been found to explain any complex behavior, such as addiction. Instead, researchers suspect that multiple genes work together, along with non-genetic influences.

For example, genes may lead people to gravitate toward particular friends, jobs and lifestyles that suit innate talents and personality traits. In other words, as Scarr suggests, genes may guide people’s choices of what to pay attention to and what to ignore.

Genes may also dictate the responses people bring out in others. As Scarr puts it, a naturally cheerful infant elicits different responses than does a fussy one; as a result, the cheerful child may come to see social contact as more positive and rewarding.

“There are certain events, people, objects you find congenial,” said Nancy L. Segal, associate professor of developmental psychology at Cal State Fullerton. “These kinds of preferences are a joint product of what’s available to us and of our genes.

“What that means is we are not just passive recipients of environmental effects,” said Segal, who is studying, among other things, whether genes influence one’s sense of smell. “We are active agents in how we structure our situations.”

While skeptics do not disagree that genes influence behavior, they say it is not yet possible to measure their impact. The twin method, they say, underestimates the influence of environment and cannot prove that genes actually cause a particular behavior.

While the studies assume that twins go randomly into different households, adoption agencies tend to place them with families not unlike their own, critics say. Similar upbringing may lead to similarities in behavior that are mistakenly attributed to genes.

Furthermore, critics say the studies use simplistic measures of the environment that may make it impossible to appreciate its full impact. Aspects of behavior then may be wrongly traced to genes simply because the environmental measures are crude.

“It’s not telling us very much,” said Jerry Hirsch, a psychology professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. It is already clear that heredity is important, Hirsch said. The question now is which specific genes are involved and how they work.

And that is a puzzle, critics say, that cannot yet be solved.

“We don’t have any techniques for answering the question,” said Leon J. Kamin, chairman of the psychology department at Northeastern University. “When people give you a confident answer, it is based more on social and political ideology than on objective facts.”

Genetic hypotheses go in and out of vogue, argues Richard M. Lerner, a developmental psychologist at Michigan State University. He said they come into fashion in times of social unrest and political conservatism, when people want simple answers to complex problems.

“There is a tremendous, reactionary biologizing of human behavior,” Lerner argued. “It’s a search for overly simplistic answers. The fact of the matter is, biology is a part of all human behavior. But that doesn’t mean you need to resort to . . . genetic reductionism.”

Proponents of behavioral genetics deny they are guilty of such sins. Few if any traits, they say, are influenced primarily by genes. They say their research illustrates the impact not only of genes but of environment--and in different ways than traditionally thought.

For example, past studies of upbringing focused on factors such as social class that are shared equally by members of a family. Plomin says it now appears that the most influential environmental components are those that are not shared.

Such factors, experienced differently by each sibling, may include how a particular child is treated by parents, how each is treated by siblings, birth order, spacing, gender, the quality of close friendships, and school, marriage and work experiences.

In Scarr’s opinion, the new findings challenge current notions about child-rearing. She suggests that “good enough, ordinary parents” have the same influence on their children’s development as “culturally defined superparents.”

Children’s development and outcome depend less on whether their parents take them to museums than they do “on genetic transmission, on plentiful opportunities” and being in an environment that enables them to “become themselves,” she said.

Scarr suggests that parents focus more on ensuring that their children feel “competent, loved, whole and able to cope with the world,” and devote less time to trying to shape their intellectual development to mold the child.

“The best job you can do is to provide each child with the kind of support and opportunities that he or she needs to do the best they can,” said Scarr. “Not that each child needs the same opportunities. Each child needs an individually tailored environment.”