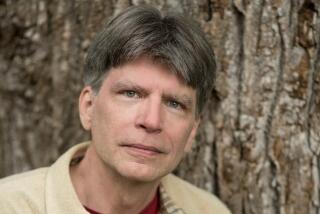

God Helps Him. . . : SEA LEVEL, <i> By Roger King (Poseidon: $20; 256 pp.) </i>

- Share via

Fleeing his globe-trotting job with an international development agency, Bill Bender holes up on a tiny Polynesian island. He lolls about, swims in the lagoon, hangs out with Emo, whom he once made love to and whose baby may be his. And he devises an act of atonement for one piece of the philanthropic corruption that has made up his career.

It is a matter of pigs. The inhabitants of Ruatua had lived peacefully, fishing, cultivating breadfruit and occasionally eating one of the little brown pigs that run wild. Then Bill’s agency arrived seeking something to improve. It introduced big white pigs that could be fattened, butchered and sold. They required imported feed and antibiotics, of course, and the islanders had to borrow to pay for them. This was foreseen; sales were to compensate. Except for one thing: In Ruatuan society, pigs are something to be given and taken free.

And so when Bill returns, fed up with the meaninglessness of modern life and international philanthropy, he invokes another old tradition: a series of stranger-feasts paid for by the guest of honor. He buys a white pig for each one. Banquet by banquet, bite by bite, he relieves the island of its ruinous porcine progress.

Roger King, an Englishman who once worked for an unspecified international organization, has written a novel that sharply satirizes such institutions. Aid, as he sees it, is an instrument of power and prestige; agreements are made between donor or lender governments and agencies, and the political elite of the recipient nations. It is a network of mutual benefits, made with only vague reference to the needs of the populations, and often working out to their detriment. As Bill says in a previous job:

“I’m not traveling around the world to help the poor. I work for the World Bank.”

When the book begins, Bill is in Pakistan’s Himalayan foothills trying, with the help of two Japanese colleagues, to find a project to finance. The civil war in Afghanistan is going on, and the area is geopolitically hot. Everyone wants a piece of the action: the American Agency for International Development, the World Bank, Germany, Switzerland, the United Nations.

A suitable Pakistani request is worked out, subject to two conditions: A powerful local official will be put in charge of disbursements; for his part, he will request a much bigger credit than he had originally intended. Like other international agencies, the Development Credit Agency, based in Geneva, is esteemed by the size of its loans.

Bender, with some qualms, has become a cynic about such things. When he and his colleagues, on a bumpy tour of the countryside, are taken not to the village they requested but to the one that is most prosperous, he makes only a token protest. He realizes that, what with their escort--provincial officials, the chief of police--they will only hear what they are supposed to hear; but he rationalizes:

“What might seem a conspiracy to conceal the truth beneath official misrepresentation might equally well be interpreted as the expression of human goodness, each individual guarding the welfare of the family that depended on him. And the official version--however fantastic--did at least have the virtue of public definition; it was a basis for doing business.”

Clearly, Bender is far gone. When word comes to their remote base that his father has died back in England, he procrastinates about returning to see his mother. Interrupting his assignment could earn him bad marks with his superiors in Geneva, he reflects. He has a counter-scruple: One or two of his superiors are Indian; will they blame him for lack of piety if he doesn’t go? He doesn’t; instead, he has a breakdown, and will end up--temporarily at least--on his island.

If the accounts of international boondoggling and logrolling make for some shrewd satire and absurdist humor, the more ambitious fictional development of Bender’s collapse is much less successful. The author is attempting a portrait of modern existential sickness, and he hasn’t done it very well. The story of Bender’s activities in Pakistan and his counter-activities on Ruatua are interwoven with long italicized passages dealing with his family, his childhood, his love affairs and his partly hallucinatory speculations and obsessions.

He meditates on his father, a milkman in the working-class London suburb of Tottenham and, occasionally, a lay preacher at the Baptist church. He is a steady, patient, earth-bound man--he journeyed as far as Dieppe once, and didn’t like it--and the thought of him makes Bender feel guilty and insubstantial. At one point, he invents a whole secret life of adultery and embezzlement for his father; at the end, it seems that one or two details may have been true; nothing is determinate.

With more ambition than success, King weaves large images of the world’s unsoundness into Bender’s uneasy meditations. He is obsessed with the fact that the world is round; he jets here and there and gets nowhere, neither farther away nor nearer to himself. Lying in the water at Ruatua--sea level--he looks west and imagines he sees all the way to Europe, to “the pretty Alps of Switzerland,” to Dover. Looking east, his imagined gaze hits England once more, this time from the Cornwall end. He thinks such thoughts as:

“Though it can be conceded that human civilization is responsive to material reality, the specific responses draw on the possibilities for life that pre-exist in man. Rather than being inevitable, civilization is an expression of our innate human potential. . . .” and so on.

Whether this orotund emptiness is the author’s, or whether he is using it as a symptom of his character’s empty malaise, doesn’t, in the end, much matter. Either way, he has lost hold of Bender; he employs him much better holding up the World Bank.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.