Boom in Swaps Is Welcome to Some but Worries Others : Securities: The value of the complex issues has soared to $5 trillion--a figure that raises fears that a crash would be staggering.

- Share via

NEW YORK — Who says the space program is moribund? For the last 11 years, the rocket scientists have been hard at work--Wall Street rocket scientists, busy creating ever-more-exotic financial vehicles that are soaring into the stratosphere.

From liftoff in 1981, the market for swaps--complex deals used by companies, financial institutions and governments to manage their exposure to interest-rate changes, currency fluctuations and commodity price variations--has soared to perhaps $5 trillion in outstanding agreements.

Swap growth, nothing short of phenomenal, has been such that the market’s nominal value far outstrips that of junk bonds and stock index futures. In fact, $5 trillion is more than the value of all the stocks on the New York and Tokyo exchanges combined.

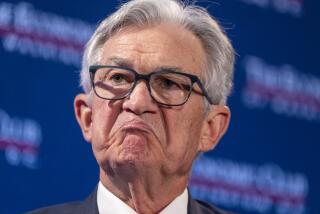

The swap market has gained altitude so fast that some people worry that it might crash and burn. As president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and one of the world’s most astute bank supervisory officials, E. Gerald Corrigan is not known as a man who cries wolf. So when Corrigan issued a public warning earlier this year about the burgeoning market, people took notice.

“High-tech banking and finance has its place, but it’s not all it’s cracked up to be,” Corrigan said in a January speech to bankers. The rapid growth of the swap market “should give us all cause for concern,” he said. “I hope this sounds like a warning, because it is.”

Fast forward to May: Olympia & York Developments Ltd., the world’s largest real estate developer, seeks bankruptcy court protection in Toronto, New York and London. The failure of O&Y;, a major user of swaps, sends shivers through global markets, including the market for swaps.

Yet when the figures were tallied, the net credit exposure of banks to O&Y;’s swap transactions was a mere $78.2 million, compared to O&Y;’s total debt of $18 billion.

“That’s a big swap event?” asked Mark C. Brickell, a vice president of Morgan Guaranty Trust Co. and a director of the International Swap Dealers Assn., a trade group.

Loan losses in the O&Y; bankruptcy, he said, will be “monumentally higher” than losses from swap activities: “The plain fact is that the credit quality of swap portfolios tends to be relatively high compared to other banking activities.”

Nevertheless, recent events and the new prominence of swaps in global finance have focused attention on this little-known and even less-understood set of financial transactions. The world of swaps is an insular business with its own lingo: The financial wizards who craft the exotic vehicles are known as rocket scientists, and some swaps that allow the parties to hedge against interest rate and currency risks have so much going on that they are called circuses.

Swaps first came to prominence in 1981. That was when Salomon Bros. engineered a transaction between International Business Machines Corp. and the World Bank that allowed the bank to achieve its desired Swiss franc funding, and IBM its preferred dollar funding, at substantial cost savings to each.

The essence of a swap contract is the binding of two parties--called counterparties--to exchange two specific payment streams over time. Consider a typical interest-rate swap in which the counterparties agree to exchange a stream of fixed-interest payments for a floating-rate stream.

A small- or medium-size company without access to fixed-rate financing is thus able to convert a variable-rate bank loan into a fixed-rate loan. The smaller company does this by “swapping” payment obligations with a larger company that does have access to the fixed-rate market. The big firm, which could prefer variable-rate financing for any number of reasons, gets a break on its interest rate for lending its fixed-rate financing ability to the counterparty.

Swap dealers--banks, securities firms, insurers--make money by bringing the two parties together. Sometimes they also participate in swaps they arrange.

There are several risks in swap transactions, but the biggest, everyone acknowledges, is credit risk. What happens if Company A, which under the swap is obligated to make the payments on Company B’s debt, goes under? And could one missed payment lead to a catastrophic chain reaction, causing the entire financial system to seize up?

“Off-balance sheet activities have a role, but they must be managed and controlled carefully, and they must be understood by top management, as well as by traders and rocket scientists,” Corrigan said in his speech. “They also must be understood by supervisors.” He said regulators “are redoubling our efforts” to ensure that supervisory policies “are sensitive to the full range of risks” that swaps present.

Swap fans insist that fears of a swap-inspired financial meltdown are overblown.

“The numbers bandied about for the swap market are huge, but what you really have to worry about is the net difference in the counterparties’ obligations,” said Merton Miller, a Nobel laureate at the University of Chicago.

But Corrigan believes otherwise. “The distinction between gross and net many be relevant in some cases, and it may be fine when all else is well. But in the event of a major market disruption, I assure you it will be the gross, not the net, that will really matter in most segments of the marketplace--both nationally and internationally.”

Corrigan speaks from experience. His people had to step in to help unravel swap transactions entered into by both Drexel Burnham Lambert and Bank of New England Corp. when those institutions failed. In Drexel’s case, about $30 billion in face amount of swap transactions had to be unraveled.

Still, said one swap advocate, there was an orderly market resolution to the Drexel and Bank of New England failures, and “the sell-offs did not cause a market disruption.”

Moreover, despite the persistent fears of regulators and others, swap advocates insist that swaps are inherently less risky for bankers and other participants in the market.

“It is our business to identify the risks in a transaction, to isolate those risks and to manage them,” Brickell said, adding that swaps--though suspect because so little is known about them and because it is a business conducted off a bank’s balance sheet--are less risky than traditional loans.

Why? Because only top-rated firms and banks and corporations get to play in the swaps arena. “Market forces tend to move things in a healthy direction,” Brickell said, adding: “You have more triple-A-rated swap dealers than there are triple-A-rated banks and securities firms combined.”

Indeed, the latest trend in the swaps business is for banks and securities firms to create separately capitalized swap units that are eligible for Triple-A ratings. Merrill Lynch and Goldman Sachs recently did just that.

Moreover, swap advocates argue that the corporations using bank services for swaps are precisely the blue chip customers who deserted bank lending long ago when they realized they could tap commercial paper markets directly.

“Our swap portfolios are filled with exactly the kind of names we want,” Brickell said. Besides IBM, big users of swaps include such multinational giants as McDonald’s and Philip Morris.

Brickell’s ardent defense of swappers does not mean that they are unmindful of Corrigan’s concerns. “Swap dealers think a good deal like their regulators do,” he said. “We are extremely mindful of the risks.”

Still, the International Swap Dealers Assn., in a move that is likely to please regulators, last week unveiled a new master agreement to help standardize swap transactions, reduce risks and make regulation easier.

Swap Market Growth

The swap market has grown nearly fivefold in the past five years, prompting Federal Reserve Bank of New York president E. Gerald Corrigan to warn bankers that national and international regulators are “redoubling our efforts” ensure adequate supervision. Swap transactions are used by major corporations, financial institutions and governments to manage financial risk.

Definitions:

Interest-rate swaps: In such a transaction, one party agrees to make periodic payments based on a fixed rate of interest to “counterparty,” who in turn makes payments based on a floating rate of interest.

Foreign currency swaps: In this transaction, one party agrees to make periodic payments in one currency to another party, who in turn makes payments in a different currency.

Source: International Swap Dealers Assn.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.