SCIENCE / AIDS RESEARCH : Liability Protection Needed for Vaccine Studies, Experts Say

- Share via

The refusal of a drug company to begin testing an experimental treatment that could slow the spread of the AIDS virus from pregnant women to their babies has raised new fears that firms will abandon AIDS vaccine research unless they are promised protection from lawsuits.

The concerns surfaced this week after Abbott Laboratories refused to go ahead with testing a treatment called HIVIG. The company has asked the federal government for “100% indemnification” in case the treatment inadvertently harms the babies it is intended to help.

Alarmed by the snag, experts said Thursday they fear that Abbott’s action could set an alarming precedent: If other drug companies back out of experimental trials, citing fear of liability, progress toward an AIDS vaccine could be seriously delayed.

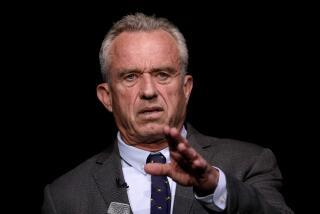

“It is important to make sure that liability is not a real obstacle to the development of vaccines,” said Robert E. Stein, a Washington lawyer who handles AIDS issues. He said that means protecting not only manufacturers but also volunteers in drug and vaccine trials.

One approach would be to set up a system like the country’s 6-year-old childhood vaccine injury compensation program. Under that system, people inadvertently injured by vaccines can be compensated out of a trust fund fed by a surcharge on each dose of vaccine sold.

Another proposed alternative is tort reform. Connecticut limits companies’ liability in certain AIDS product cases. But medical and legal experts remain divided over whether it is advisable to completely shield a firm from legal responsibility.

“The tort system still functions as a deterrent for misbehavior,” said Dr. Lawrence Miike, a professor of medical policy at the University of Hawaii School of Medicine. “That’s the argument you will always hear--that it’s not just a compensation system.”

AIDS is not the first disease in which liability worries have arisen. Vaccine research of all types has faced similar problems. Unlike drugs, usually tested on sick people, vaccines are tested on the healthy. If they backfire, they can make healthy people sick.

For that reason, vaccine manufacturers are especially nervous about lawsuits. In deciding whether to move ahead with a product, they are said to weigh the amount of profit they stand to make against the costs of research, development and litigation.

Some manufacturers have succeeded in winning protection from liability. In 1976, the government indemnified the manufacturer of swine flu vaccine. In 1986, it set up the injury compensation system to ensure that firms would keep making childhood vaccines.

But experts disagree on how real the threat of liability is in the case of anti-AIDS products. Some suspect that the issue is little more than a smoke screen used by companies to justify dumping a product that they have decided will not prove sufficiently profitable.

Experts point out that experimental drug and vaccine trials are closely monitored. Adverse reactions are picked up quickly and trials are immediately cut short. Volunteers must read and sign elaborate informed consent forms detailing possible risks.

“While liability is a problem, it is (also) easier for a company to say that liability is a factor than to say they are not going to make a profit (on the product) so they don’t want to pursue it,” said Stein, the Washington attorney.

In the Abbott case, which was to involve a nationwide trial that included institutions in Los Angeles, San Diego and San Francisco, the treatment in question is not technically a vaccine. HIVIG would be given to pregnant women infected with the AIDS virus in hopes of preventing them from spreading the virus to their infants in the womb or during labor and delivery.

About 6,000 infected women become pregnant every year. Their babies have about a 30% chance of becoming infected. In other words, most of the infants whose mothers might participate in the HIVIG trial would be born healthy without a vaccine.

That is where the concern about liability arises. HIVIG is made from the plasma of people infected with the AIDS virus. The plasma is processed to collect high concentrations of protective antibodies against the virus while inactivating the virus.

Abbott officials appear to fear a lawsuit if HIVIG inadvertently enhanced, rather than reduced, the risk of mother-to-infant transmission--a risk that Abbott officials acknowledge is small and that other researchers say is more abstract than real.

“I don’t think it is an unreasonable concern,” said Dr. Jeffrey Laurence, director of the laboratory for AIDS virus research at Cornell Medical College. But he said the trial should not be held up by the impasse between Abbott and the government.

“Someone’s got to fish or cut bait here,” said Laurence, who is also a scientific consultant to the American Foundation for AIDS Research. Either the government must set up a procedure for limiting liability, he said, or Abbott should pass the product on to another company.

Some experts, including Laurence, say the government should set up an AIDS vaccine injury compensation system like the one for childhood vaccines. People claiming injury could apply to the system for compensation; if turned down, they could then sue the manufacturer.

Several questioned the wisdom of state-by-state tort reform legislation, such as the Connecticut law. They said a federal policy is needed, and some questioned the wisdom of granting 100% indemnification.