Ancient Towns May Be Clues to Africa’s Heritage : Archeology: Arabs were long thought to be responsible for the ruins that dot the continent’s east coast. But a Kenyan scholar argues that the Swahili built them.

- Share via

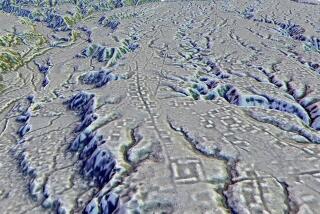

MOMBASA, Kenya — On the shores of the Indian Ocean, dotting the east coast of Africa from southern Somalia to Mozambique, are the ruins of hundreds of elegant stone towns dating from the 11th to the 17th centuries.

Until recently, most archeologists studying these ruins considered them too sophisticated to have been produced by an African society.

Puzzled by the towns’ origin and impressed by such features as elaborate plasterwork and indoor toilets, these researchers viewed them as cultural transplants from another continent, constructed by Arab traders who visited the African coast and decided to stay. But some African archeologists now argue that the local inhabitants of the coast deserve a greater share of the credit.

Recent work by a young Kenyan archeologist suggests that the stone towns, although heavily influenced by Arab culture, may have started as African settlements that gradually grew rich and cosmopolitan through trade, serving as gateways for the flow of goods between Africa’s interior and distant lands such as Arabia, India, Persia and China.

“The interpretation has changed,” said George H.O. Abungu, head of coastal archeology at the National Museums of Kenya, who performed the new research. “If you look at the culture, it’s basically African. If you look at the structure and layout, it’s basically African. That has been the case since the 7th or 8th century.”

Some researchers consider Abungu’s views radical, pointing out that the architecture, inscriptions and technology of the stone towns are more characteristically Arab. But the work has ignited new interest in the long-neglected ruins.

The people of this coast--the Swahili--were converted to Islam in about the 10th Century and shared a common language that is still spoken in East Africa. The modern inhabitants are an ethnically mixed population that probably resulted from intermarriage of an indigenous Bantu people with Arab traders and immigrants.

But much of the history of the Swahili remains mysterious. Where did they come from and when did they first settle along the Indian Ocean? Why, after living for hundreds of years in their seaside towns built of coral rock, did they abandon most of these settlements during the 17th Century?

Because of the work of the Leakey family, most anthropological and archeological research in East Africa has focused on much more ancient finds that illuminate the search for human origins. Few of the ruined coastal towns have been carefully studied.

Abungu said that of more than 100 such sites in Kenya, fewer than 50 have undergone any excavation. Most are heavily overgrown, and many are threatened by weather, erosion and encroaching land development.

Abungu and other African researchers are working to change the situation. With a grant from the Swedish Agency for Research Cooperation With Developing Countries, archeologists from nine African countries have established a regional program to study the development of urban centers along the coast and at a few inland sites.

Mtwapa, a ruined town a few miles north of Mombasa, is a good example both of the towns’ archeological value and of the challenges faced by researchers trying to preserve them.

Its ruined buildings are spread over more than 50 acres, but much of the valuable seaside land has been bought for development, and only about 12 acres are protected by the government. The site is so overgrown that, in many cases, tree trunks have encased the crumbling walls of buildings.

Between the walls run straight streets, some only about 5 feet wide and spanned by graceful arches. Many doorways are finished in porites coral, a soft coral that was harvested from under the sea and worked quickly while still wet to achieve sharp edges and fine detail in plasterwork.

“It shows you the level of craftsmanship in Swahili society,” said Abungu.

Some houses had Arabic inscriptions over their doors and decorative plaster niches that were used to hold oil lamps, pottery or scrolls from the Koran. Many had bathrooms with well-designed pit latrines and stone washbasins.

Mtwapa’s largest mosque had a spacious musalla , or main prayer hall, with a line of rectangular pillars down the center. Outside was a small stone pool where worshipers could wash themselves before entering. A conduit carried water to the pool from a cistern, and dome-shaped corals were set into the pavement by the pool to serve as foot-scrapers.

Abungu said the oldest ruins found at Mtwapa date from the 12th or 13th century but that some of the coastal towns are much older. Excavations of the earliest settlements, such as Shanga and Manda in northern Kenya, have uncovered the remains of typical round, African mud-and-thatch dwellings dating from the 8th Century. Overlying these are later stone buildings, but the town’s original layout is preserved.

Abungu said some of the coastal settlements eventually covered up to 70 acres and contained as many as 15,000 people.

“These towns grow, and by the 11th or 12th centuries you have stone structures,” said Abungu. “By the 14th and 15th centuries they reach their peak. This was the golden age of Swahili civilization.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.