Castro Visits Roots--the Hut Father Fled for New World : Spain: Cuba’s leader is declared an adopted son of Galicia. Elsewhere, he is viewed as ‘old-fashioned.’

- Share via

LANCARA, Spain — The Western Hemisphere’s patriarch of revolution spent seven minutes here Tuesday inside the one-room stone hut that his father fled for a better life in the New World.

When he emerged, Fidel Castro headed for the back garden: “I want to see the earth,” he said.

Castro’s return to his roots here in the hot green countryside of Galicia climaxed a remarkable journey through Spain--and time--that has been stalked more by pathos than passion.

In six days, one of the world’s longest-enduring political leaders has conferred with leaders of Iberia and Latin America at a summit meeting in Madrid. He has dined with the king of Spain, witnessed the opening of the Olympic Games in Barcelona, peeked at a technological Tomorrowland at Expo ’92 in Seville and ridden through the poor-no-more Spanish countryside.

Yet only here in Galicia, a region of northwestern Spain that Tuesday declared him an adopted son, has Castro encountered genuine warmth--or even a modest political echo.

“Cuba si, Yanquis no!” the young people chanted during his two-day visit to Galicia. Castro rewarded true believers by attacking the United States, inveighing against the nearly 30-year-old U.S. trade embargo at virtually every public opportunity.

Castro’s relatives and their neighbors threw him a country lunch in a nearby field Tuesday. There was hardly any political talk, for once, but plenty of local wine, grilled sardines and green peppers, hearty omelets and octopus slices swimming in olive oil.

“He is one of us, and we are proud of him. I think he is very moved to be here,” said Lancara Mayor Eladio Lopez. Said Castro: “This moment has great meaning for me. . . . My father longed for 60 years to return here but never could.”

Galicia, that fetching chunk of Spain that sits above Portugal, was a poor agricultural and fishing region that sent hundreds of thousands of its sons, like Angel Castro, to seek their fortunes in Latin America and the United States.

Since the death of dictator Francisco Franco in 1975, Galicia, like all the rest of the country, has prospered mightily under democratic rule. That was plain to see from Castro’s air-conditioned black Mercedes-Benz as he swept through Galicia with his host, regional governor Manuel Fraga, a conservative who has old family ties to Cuba.

It is no secret to Spaniards, by contrast, that Cuba, where Castro has ruled since 1959, did not prosper during decades of massive Soviet aid, that Castro rejected perestroika and that economic times on the Caribbean island are leaner than ever today, with scant prospects of improvement. On Tuesday, officials in Havana announced new cutbacks in rail service because of a throttling fuel shortage.

“I hate to say this, and I don’t want my name on it, but. . . . Once, Castro was a beacon for us while we were fighting Franco, but now he’s . . . I guess you’d have to say he’s old-fashioned,” said an official in Spain’s ruling Socialist Party.

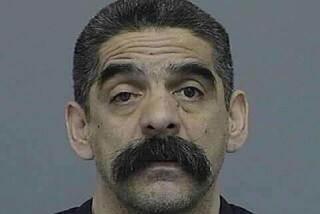

Castro is 65 now. The beard and hair are an imposing gray, and the eyes burn as fiercely bright as ever, but he walks stiff-gaited and cautiously, as if measuring each step for the effort it will require.

In Spain, he appeared to favor his right leg, and his trademark gesticulations seemed to have slowed a beat. Aides variously confided that he was tired, jet-lagged, that he had an earache. No sooner had he arrived than the Galicia visit was cut from four days to two.

Security concerns were the main reason for shortening the trip, Spanish newspapers said. To counter threats from Cuban exiles who dogged his every step, Castro’s security seemed like a Cold War leftover. With arrival time unannounced, two Cuban planes swooped into Madrid in the middle of the night, those on the ground apparently unsure from which aircraft the Cuban president would emerge.

Castro loyalists from Havana shepherded their leader at every turn, but one of them, a video technician, will not be aboard when the Cuban party returns home today: He is asking for asylum in Spain.

Traveling through a country that has transformed itself in a breathtaking few years from dictatorial backwater to full partner in a uniting Europe, Castro sounded almost disconnected at times, hawking yesterday to a people wedded to change and betting on tomorrow.

There were few takers. At the summit meeting of Spain and Portugal and their former colonies, Castro was the only dictator present, the only head of state in a uniform and the only one to support the one-party state and a command economy.

The other leaders wondered how to draw Latin America and Iberia closer together. Castro attacked the United States, urging the others to unify against it, blaming Cuba’s economic woes on the American embargo.

Spanish Prime Minister Felipe Gonzalez, who, like many Latin American leaders, thinks the U.S. embargo is a mistake, told summit reporters that Cuba’s problem is due more to a Soviet-inspired economic system that does not work.

Other leaders let it be known that they had privately urged Castro to climb down off his lonely Marxist horse but that he waved them off. Cuban officials, though, say there was no arm-twisting.

“We were treated in Madrid with the same affection and respect as everybody else,” said Foreign Minister Ricardo Alarcon.

At Barcelona, Castro waved and clapped, but the big crowd at the Olympic stadium was cold to the Cuban team during the opening ceremony. At Cuba’s Expo pavilion in Seville, Castro wound up in a shouting match with a Cuban exile from Miami. Spanish newspapers said that during the world’s fair visit, Prime Minister Gonzalez urged Castro to call free elections within a year. They said Castro replied that Cuba already enjoys “more democracy than in any other country on the planet.”

Escorting him home to Lancara on Tuesday, Gov. Fraga, the longtime head of Spain’s largest conservative party, reminded Castro of traditional Galician virtues: “We are a hard-working society, defenders of our property, however small it may be. We have never trusted the utopian promises of governments . . . and we know the difference between what is public and private.”

Castro had larger issues on his mind: “We are writing a heroic page of history, facing the most powerful country in the world that seeks to asphyxiate us, to kill us through starvation,” he said. “But we will conduct ourselves as worthy sons of Galicians. You will never be ashamed of us.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.