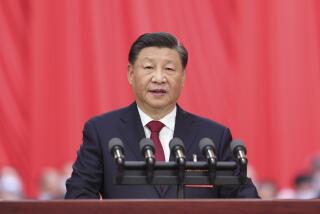

Work Harder but Keep Quiet : Beijing Party congress proposes economic dynamism without political liberalization

- Share via

China’s senior leader Deng Xiaoping was the invisible man during the Communist Party congress in Beijing, tottering on stage only after the secret sessions ended to give his blessing to a new top echelon led by economic reformers and technocrats.

But though the aged and still highly respected Deng was absent in body from the party’s first congress in five years, his influence was pervasive. Deng’s program of easing state economic controls as the surest path to prosperity was reaffirmed. So was the hard-line stand he and other party leaders have taken against political liberalization. They believe that Mikhail S. Gorbachev failed in the Soviet Union because he fostered political liberalization simultaneously with economic restructuring. They are convinced that China can continue to modernize and prosper even as the party retains its monopoly on political power and its decisive voice on cultural and social matters.

They may be right, for a time. Taiwan and South Korea provide interesting models of how explosive economic development can occur even under authoritarian and sometimes brutal regimes. These examples, however, can be pushed too far. Authoritarian rule is vulnerable to challenge whenever economic development produces a middle class determined to have a greater voice in its country’s affairs. That is why South Korea has democratized and why Taiwan is moving steadily in that direction. China’s communist rulers are assuming that opportunities for a better material life will induce political quietism in the population. A better chance is that, eventually, the opposite may occur.

Little emerged from the party conclave in regard to China’s foreign affairs, but at least in terms of U.S.-China relations some bumps in the road can be foreseen. If Bill Clinton is the next President it can be expected that Washington will take a harder line on human rights abuses in China. A tougher stance might also emerge toward Beijing’s arms sales to volatile Third World regions, like the Middle East. And under prodding from its Asian allies Washington could also become more open in expressing its concerns about China’s own extensive military modernization program, asking why it’s needed.

A final element to consider: Deng Xiaoping, now 88 and ailing, cannot be expected to remain a key player for much longer. In its long history China has seen many periods of turmoil and uncertainty after a leader dies or is overthrown. The post-Deng era could give rise to another such period.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.