Dallas Program Offers At-Risk Minority Men a Chance to Turn Their Lives Around : Self-esteem: Classes on job preparedness, character development, reducing drug and alcohol abuse, reading, computer literacy and health and fitness transform lives.

- Share via

DALLAS — Durale Bollin has always had a good head for business.

As a 16-year-old high school dropout, he made about $1,000 on a good day selling drugs. But when he realized that outstanding debts on the streets often are settled with gunfire, he decided to get out of the business.

“I would stand on the street corner and pray that I wouldn’t die doing this,” said Bollin, now 19 and working on his general equivalency diploma.

He’s changing his life through one of 18 programs nationwide funded by the Rockville, Md.-based Office of Minority Health and designed to help build self-esteem among minority men.

Eric Anderson, director of the Dallas Urban League Institute for Minority Males, which administers the program in Dallas, said Bollin is the “illegal entrepreneur-type” he knows well.

“The brilliant ones are successful in the street,” Anderson said. “To run a drug operation, you’ve got to be smart. You’ve got to make contacts, you’ve got to market it, you’ve got to sell it.

“We try to break the cycle, to get them to see there’s a different way to use their skills.”

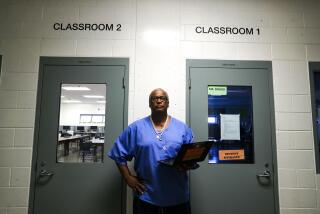

The institute is located on the campus of Paul Quinn College, a black liberal arts college in southern Dallas County.

The average participant in Dallas is black, 22 years old, a high school dropout, addicted to drugs or alcohol and living with his mother. He has one or two children and has given up looking for employment or is selling drugs, Anderson said.

Seventeen- to 38-year-old minority males are eligible for the Dallas program. Similar programs in Window Rock, Ariz., and Bayfield, Wis., target American Indian men. Programs in Portland, Ore., and Santa Fe, N.M., target Latinos.

The Office of Minority Health says minority males have the highest rates of mortality, hypertension, cancer, chronic and infectious diseases, and suffer most from such problems as incarceration, poverty, low insurance coverage, unemployment and teen-age fatherhood.

“They don’t feel as though they are a part of the overall society,” Anderson said. “A lot of them are talented, intelligent individuals. But . . . they’ve gone in the wrong direction.”

Four months of classes on job preparedness, character development and self-esteem, reducing drug and alcohol abuse, reading, computer literacy and health and fitness “transform the way they approach life,” Anderson said.

Ten men graduated in January, completing the third session since the program began in September, 1991. About 30 men are enrolled for the fourth session, Anderson said. The cost for ushering about 40 participants through the program is about $70,000, he said.

Most of the men who begin each session hope it will help them find jobs--not an easy task when more than half have criminal records.

Several black business leaders try to help. “The young people were saying, ‘We can’t get jobs. We can’t get jobs,’ ” said Lamarr Vines, general manager of Dallas’ Radisson Hotel and Suites.

“As I talked to them I found out that people were not properly filling out job applications,” he said. “They weren’t even making it to the interview process.”

Bernard Skinner, 20, who graduated from the first four-month session, is taking freshman courses at Paul Quinn to get into nursing school. The former gang leader credits the program with helping him get his GED and a job as a shift manager at a fast-food restaurant.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.