SPECIAL REPORT / ON THE STATE OF HUMAN RIGHTS : The Two Sides of Humanity : Our Ability to Do Evil Equals Our Ability to Deny It : Behavior: Psychological mechanisms enable ‘good’ people to commit atrocities; it’s simple human nature.

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The greatest religious texts wouldn’t always be exhorting us to do good if they didn’t recognize that we’re inclined, so often, to do evil. At the simplest level, doing evil means doing harm, intentionally and unjus tifiably, to others. The capacity to do evil seems to be part of being human. We usually think of it as residing in our souls. It may be deeper than that. It may be, somehow, in our bones.

But it also seems to be part of being human to feel uncomfortable about doing evil. Were we to acknowledge to ourselves that we are doing evil, we’d feel one of the most discomfiting of human emotions--guilt. And were we to acknowledge to others that we’d done evil, we’d feel an emotion hardly less discomfiting--shame.

We can avoid these feelings, of course, by following the religious exhortations--that is, by not doing evil in the first place. Or we can avoid them, or at least minimize them, by persuading ourselves, through some psychological stratagems or mechanisms, that the evil we’ve done really isn’t so evil, or even that it’s really something good.

It is, in the main, the use of such psychological mechanisms that, through the ages, has enabled ordinary people to do extraordinary evil. Usually, these people carry out heinous acts in response to the orders or expectations of persons in authority, or in the service of a revered goal. In most cases, those who inflict harm on others while carrying out their duties must resort to one or another psychological mechanism to justify and even ennoble their actions so as to avoid the human feeling of guilt. Unfortunately, our century is no different from those that came before in providing countless examples of such acts of evil, as well as of the kinds of psychological mechanisms that have made such acts possible for those who have carried them out.

During this century’s first half, it was ideology that fueled the lion’s share of human destructiveness. During its last half, other forces have taken the place of ideology as the primary sources of such evil in the world. Those forces--nationalism and religion--have played that role, with great success, before. They’re likely to play it with even greater success in the future.

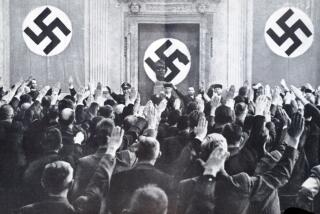

The harm visited by ideology upon innocents earlier in this century conferred upon the practice of evil unprecedented dimensions of depravity and scale. Nazism invented a ferocious machine of focused death. And communism, though less systematic in its methods of killing and not obsessed with race as a basis for it, destroyed human life with no less success. In both cases, the bureaucrats who gave the orders and the ordinary soldiers or policemen who carried them out found it possible to do so without concluding that they were evil.

More recently, with Nazism having been defeated and communism having collapsed, nationalist and religious sentiments are once again mobilizing mass ferocities. Legions of men, until recently ordinary civilians, are committing heinous acts against persons who once were neighbors and friends, all the while feeling fully justified and even virtuous.

Strikingly, the psychological mechanisms that have enabled people to commit atrocities while fighting for causes--whether ideological, nationalistic or religious, and whether in this century or some earlier one--have been the same.

One of the most effective mechanisms is simply to see harm as good because the person who is to be harmed is bad--because he or his people have brought harm to one’s own group and therefore deserves punishment. Moreover, if allowed to live, he will no doubt bring harm to one’s people again. From this perspective, killing is seen as a social benefit--indeed, a self-protective necessity--and leaders strengthen this perspective by summoning up or inventing atrocities, contemporary or historical, that make killing seem compellingly justified. Another psychological mechanism that makes it easy to harm others is to couch the harm in euphemistic terms: We aren’t sending someone to a gas chamber, we are slating him for “special treatment”; we aren’t destroying an entire population, we are engaged in “ethnic cleansing.” The language we use has a powerful effect on how we think about the actions described by that language, and leaders understand the necessity of providing language that will enable those who are assigned to perform atrocities to do so with a less troubled conscience.

Moreover, it’s easier to harm someone if we believe that the authority who has defined the harm as necessary and good is also, ultimately, responsible for it. And it’s easier to harm someone if we play only a small part of the process--if we are, say, only loading a cattle car with Jews but not administering the gas at the train’s destination, or if we are only maintaining a siege around Sarajevo but not firing mortar shells into a cemetery full of mourners.

Finally, it’s easier to harm other human beings if we believe that they’re less human than we are. It’s no accident that, in times of conflict, each side attributes to members of the other side non-human characteristics: Enemies are vermin, creatures that not only may be killed but, as a matter of public health, should be killed. Even better is to identify the enemy in inanimate terms; the Nazis often referred to inmates in death camps as logs, making it a much less vexing matter to dispose of them.

But whatever the psychological justification, and no matter how blameless and even virtuous the person doing the harm feels himself to be, his act is evil. Though it can be explained and even understood, it must also be condemned. And with the condemnation of the act must come the condemnation of the forces--whether ideologies, nationalisms or religions--that create the circumstances in which doing evil is perceived as doing good.

The enormous task before us, both in the years remaining in this century and in the next millennium, must be to recognize and moderate the flaws in ourselves and in our institutions that make such evil possible. It would be an impossible task, of course, to eradicate those flaws; it’s in our nature as psychological creatures that we can tap mechanisms to justify the worst in us, and it’s in our nature as members of groups or as believers in ideas to find justifications within the group or the belief to harm persons who are members of different groups or who believe in different ideas. The best we can do, as individuals and as nations, is to recognize evil when it occurs, and to recognize that to do nothing about it when we are in a position to stop it or at least to protest it is to participate in it, in some way, ourselves. We owe that to the victims. We owe it to the victimizers. And, as human beings susceptible to committing our own evil acts and psychologically adept at the art of transforming what is truly evil into something that seems somehow good, we also owe it, emphatically, to ourselves.