Health Horizons : MEDICINE : New View of Ulcers : Research now traces ulcers to chronic infection of stomach lining.

- Share via

Two and a half years ago, Michelle had an ulcer. In fact, she’d had one about every 18 months for nearly 10 years, and knew that increasing the dose of her anti-ulcer medication would take care of her problem. But in late 1990 her physician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., decided to try a different approach. He still prescribed Zantac, the anti-ulcer drug, but he added two antibiotics and Pepto-Bismol to her therapy. Michelle was concerned about the inconvenience of taking so many pills (up to 11 a day), but her physician, Dr. Nicholas J. Talley, told her it would be worth it.

It was. Michelle’s ulcer never came back. No more discomfort or upset stomach. No more visits to the doctor and expensive medication. No more ulcer.

For the past 30 years, ulcers were blamed on elevated levels of stomach acid, brought on by stress, smoking and other behavioral factors. Researchers concentrated on developing ever more powerful antacids to combat duodenal and peptic ulcers.

Although anti-ulcer drugs such as Tagamet and Zantac have become more effective at quelling the symptoms of ulcer disease--and in the process have become among the best-selling drugs in the world--they still do little to prevent the recurrence of the ulcer.

According to a small group of researchers, however, the reason for this failure to cure ulcer disease is now clear: Ulcer formation has little if anything to do with increased levels of stomach acid, they say, and everything to do with a chronic infection of the stomach lining.

This revolutionary view is so simple, some find it hard to believe. Rarely has an area of medicine been so completely transformed at such a basic level.

“Get rid of the infection, and the ulcer goes away for good,” said Dr. Barry J. Marshall, associate professor of medicine at the University of Virginia Medical School in Charlottesville and the leader of the renegades. The only exception appears to be in arthritis patients whose ulcers result from taking large doses of anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin and ibuprofen.

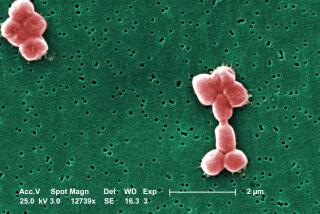

A decade ago, Marshall and pathologist Dr. J. Robin Warren discovered that a spiral-shaped bacterium named Helicobacter pylori (HE-li-co-bac-ter pi-LOR-i) was present in the stomachs of ulcer patients Marshall examined at the Royal Perth Hospital in western Australia. Treating these patients with antibiotics and bismuth, the active ingredient in Pepto-Bismol, cured the infection and the ulcers. Marshall published his results in the British medical journal Lancet, but his findings were widely derided. Everyone knew that too much stomach acid produced ulcers.

Nevertheless, Marshall persisted with his studies. At one point, desperate to be taken seriously, Marshall dosed himself with the bacterium and soon developed severe gastritis, the immediate precursor to ulcer disease. He then treated himself with bismuth subsalicylate, amoxicillin and metronidazole, also known as Flagyl. The infection, and his symptoms, went away and he never developed full-blown ulcers. That stunt, said Walter L. Peterson, a gastroenterologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas, got the medical community’s attention and focused attention on Helicobacter and its link to digestive disease.

Several groups worldwide began studying Helicobacter, and in just a few years researchers were convinced that the bacterium caused ulcers. Still, practicing physicians were skeptical. But last May and again last month, Marshall was finally vindicated. Large clinical trials conducted in Houston and Austria found that only 13% of the patients treated with Zantac plus antibiotics suffered a second ulcer, and those patients who did relapse still had traces of the bacteria in their systems. In contrast, more than 85% of patients treated with Zantac alone for two weeks suffered relapses within two years. Half the ulcers flared up within three months.

The implications of these results are enormous for ulcer patients and for a national health care bill. For ulcer sufferers it should mean the end of a virtual lifelong dependence on one of the four anti-ulcer drugs that are all among the top 10 highest-selling pharmaceuticals in the United States and Europe. A typical ulcer patient takes one anti-ulcer pill a day, which costs more than $900 a year. It is no wonder that anti-ulcer medications had sales in the United States exceeding $5.6 billion last year.

The new therapy, consisting of six weeks of anti-ulcer medication plus two weeks of Pepto-Bismol and the antibiotics Flagyl and either tetracycline or amoxicillin, costs about $150. The anti-ulcer drug heals the stomach lining, while the antibiotic kills the bacterium. No more ulcers, no more drugs. And because recurring ulcer disease would become a thing of the past, expensive ulcer surgery should become rare as well, proponents say.

Other savings should come from new laboratory tests that will make most endoscopic exams, at $150 apiece, unnecessary. One such test, developed by the San Diego biotechnology company Quidel, can be performed on a blood sample in the doctor’s office. The results are available in seven minutes.

Because a bacterium is involved, it should also be possible to develop a vaccine that would prevent the infection. Pharmaceutical giant Merck recently held a scientific meeting to determine the feasibility of developing such a vaccine and is now considering whether to proceed with this project. Meanwhile, several biotechnology companies, including Chiron in Berkeley, are working on one.

Should a vaccine become reality, its significance would extend far beyond ulcers. Evidence gathered by a number of research teams strongly supports the idea that Helicobacter infection is a necessary early step in the development of gastric carcinoma, the second most prevalent form of cancer worldwide. If so, a vaccine against Helicobacter theoretically could wipe out a major killer.

Scientists are finding Helicobacter interesting as well. Dr. Martin Blaser, professor of microbiology and director of the division of infection diseases at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn., said Helicobacter has a number of traits that are rare in the bacterial world. To begin with, Helicobacter requires only minute amounts of oxygen to survive, quantities consistent with the oxygen level common in the thick, mucous gel that coats the stomach lining. In addition, Helicobacter’s spiral-shaped and powerful whip-like structures, called flagella, enable it to propel itself through the mucous lining, which is thick enough to stop most bacteria.

But perhaps Helicobacter’s most interesting feature, said Blaser, is an unusual enzyme. This enzyme, called urease, converts the small amount of urea present in the stomach into ammonia and carbon dioxide. Ammonia neutralizes stomach acid, which makes the stomach a more hospitable place for the bacteria to live.

These traits, said Blaser, combine to give Helicobacter the exceptional ability to colonize the human stomach. “The stomach has evolved a number of sophisticated defenses that normally protect the stomach lining from infection,” Blaser said. Helicobacters can overcome these defenses and make a home for themselves in this otherwise inhospitable environment.

One of the many mysteries surrounding this bacteria is how it is transmitted. Blaser said infection is most common in places where sanitation is poor, suggesting that the bacteria is spread by contact with human waste. “This would explain the high prevalence of the bacteria in less developed countries, but it doesn’t explain how transmission occurs in the U.S. and other developed countries,” Blaser said. One possibility is that Helicobacter is spread by kissing because the bacterium is present in low levels in the saliva of ulcer sufferers.

Another mystery is why many physicians still balk at the idea that ulcers result from a bacterial infection. “It’s crazy,” Marshall said. “The evidence is overwhelming that Helicobacter causes ulcers, yet most doctors continue to rely on Zantac or Tagamet alone to treat ulcer disease.”

One reason may be that the pharmaceutical industry, which stands to lose billions of dollars, continues to downplay the link between Helicobacter and ulcer disease, and doctors get much of their information about new therapies from drug company literature.

Dr. Steven B. Gerber, investment analyst at Oppenheimer & Co. in Los Angeles, said drug companies estimate that fewer than 10% of ulcer patients would meet the criteria of those treated in the two published clinical trials.

However, doctors at the Mayo Clinic appear to have a different view, and they treat a majority of duodenal ulcer patients with antibiotics. Even pharmaceutical industry officials say drug companies are planning to formulate pills containing an antibiotic and an anti-ulcer drug.

Another reason may be the basic conservatism that runs through the medical community.

“The evidence just isn’t good enough for me to change the way I treat ulcers,” said Dr. Richard Hadden, a physician at the University of Minnesota Medical Center. “Sure, you can show that the bacteria are present in ulcer patients, but that doesn’t mean they cause the ulcer.”

“Doctors are slow to change,” Blaser said, “but they will come around eventually.”