A Tug of War for the Pages of History : Boston University claims Martin Luther King wanted his papers there. King’s widow says they belong in Atlanta.

- Share via

BOSTON — The trial in progress these last three weeks in a drab corner of Suffolk County Court here would seem at first glance to be a struggle between a family and a university, heavy with reminders of the slender distinction between what is morally right and what is legally correct.

But just below the surface is a collision of two powerful personalities--Coretta Scott King, widow of the slain civil rights leader, and John R. Silber, president of Boston University.

And looming above both is a bigger presence still--the near-mythic figure of the late Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“Every time his name is invoked, it’s done with a certain reverence,” said Lawrence Elswit, a university attorney. “Sometimes it is almost as if he were here.”

In a letter sent to university officials in 1964, King chose the library at Boston University, where he earned his doctorate in theology in 1955, as the repository of “my correspondence, manuscripts and other papers, along with a few of my awards and other materials which may come to be of interest in historical or other research.”

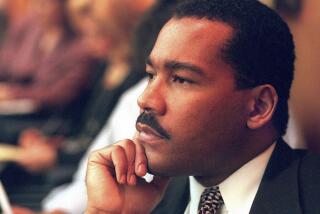

His widow is suing the university, charging that sometime before his assassination in Memphis in 1968, King had doubts about deeding his personal papers to a northern, “predominantly white institution.” Coretta King is seeking to regain 83,000 documents--about one-third of her husband’s life’s work--so they can be housed at the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta.

With her four children watching from front-row seats, Mrs. King testified on her 66th birthday that her husband regarded BU merely as a temporary haven for his writings. The family home had been firebombed and King “was being continually threatened during his lifetime,” she told the jury.

“He wanted to make sure they were safe for the time being, and Boston seemed to be the only place,” Mrs. King said. “Martin still felt his papers should be returned to the South at some point.”

But university officials insist--and Mrs. King concedes--that the Nobel Prize-winning activist failed to notify BU of any change of heart.

Earle Cooley, a portly, pugnacious trial lawyer who is representing BU, dismissed reports of conversations King may have had about moving the papers prior to his death.

“They say he changed his mind before he died, but we never heard from him,” said Cooley, a BU trustee. “If he had notified us, we would have turned them over in a minute--in a heartbeat.”

Cool and composed throughout several days on the witness stand, Mrs. King attracted a steady stream of spectators, including old friends and admirers such as former Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young. She testified that Silber, the fiery Texan who became BU’s president in 1971, had “intimidated” her eight years ago when she met with him in an attempt to retrieve the papers.

She held firm in her position that her husband’s intent was to return his papers to the South, although he never expressed that wish in writing.

“I could know what he was thinking,” she said at one point. “I read him.”

Silber attracted a sympathy vote of his own when he hobbled to the witness stand on crutches Monday, 48 hours after undergoing knee surgery. Silber’s quick, often sharp tongue was seen as the major cause of his narrow loss in the 1990 gubernatorial election here. Like Mrs. King, he is often portrayed as domineering and demanding.

He matched Mrs. King’s composure, however, by testifying in quiet, measured tones that “Martin Luther King, like Lincoln, belonged to the ages,” and by recalling how, as a young philosophy instructor, he had used King’s writings to “bring relevance” to Plato. He remained adamant that Mrs. King failed to raise the subject of her husband’s wish to move his papers until 1979.

At various times, both sides in the dispute say they have discussed possible settlements, including an offer by BU to photocopy all of its materials for the King Center in Atlanta and provide a rotating exhibit of some original papers.

But Mrs. King said she will accept nothing less than the full consolidation of King’s works in Atlanta. Sending a portion of his collection to Boston in the first place “was like giving away a part of yourself,” she testified. “The papers should be (in Atlanta), where the history unfolded.”

The jury is expected to begin deliberations this week.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.