NEWS ANALYSIS : America’s Arab Allies Uneasy About Use of Force Against Iraq : Mideast: A new wave of anti-American extremism is feared. They warn that Hussein’s regime may be left stronger than ever. Saudi editor sees skepticism toward U.S. policy.

- Share via

AMMAN, Jordan — Widespread Arab condemnation of last weekend’s U.S. missile attack on Iraq has underscored growing unease among America’s Arab allies over the use of military might at a time when many Arabs are no longer convinced that the Iraqi regime can--or should--be toppled by force.

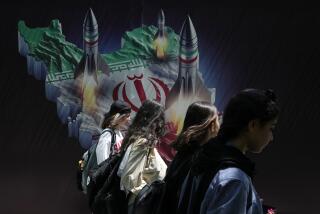

Though Iraqi President Saddam Hussein has few allies left in the Middle East, the cruise missile strike against Baghdad, combined with perceptions that the United States has not moved strongly enough to push the Arab-Israeli peace process forward, has sparked fears of a new wave of anti-American extremism and of a regime in Iraq that is stronger than ever.

“The U.S. would be well advised to calm down. Because they may not realize how explosive the situation really is,” one senior Arab official said. “We are talking about areas where the world’s energy is found, and where when people go mad, they really go mad.”

The attack against Baghdad is almost universally viewed in the Arab world as an attempt to shore up President Clinton’s political capital at home. It has undermined confidence in the new Administration’s ability to conduct an effective foreign policy in the Middle East and boosted domestic support for the Iraqi regime among a population that feels increasingly besieged from outside.

“The Islamic fundamentalists are having a great ‘I-told-you-so’ day, but even the liberals are invoking the curse of whatever gods they have on America. Even America’s die-hard supporters don’t say anything, because they don’t have anything to stand on. The mood here is one of apprehension and skepticism,” said Khalid Myeena, a senior newspaper editor in Saudi Arabia.

“I think the U.S. is losing a lot, and that guy in the White House is perceived as a fool, an enfant terrible, “ he said.

Jordanian political analyst Jamal Shaer said Arabs continue to be troubled by the fact that the United States has declined to use military force to protect the Muslims in Bosnia-Herzegovina while repeatedly striking at Muslims in Iraq and Somalia.

“I consider myself a friend of America, but on the 4th of July I cannot go to the celebration at the American Embassy. I simply can’t,” Shaer said. “My wife is Irish, and she told me if I want to go, I must go alone. She said, ‘These Americans are criminal.’ If an Irish Catholic thinks like that, what do you expect from an Arab? I fell in love with Bill Clinton until this bombing.”

The Arab reaction to the weekend attack shows how far the Arab coalition that joined the West to oust Iraq from Kuwait during the 1991 Gulf War has moved away from any commitment to using military force.

Indeed, at a time when Iran appears increasingly threatening on the other side of the Persian Gulf and domestic Islamic extremism appears a greater danger than Iraqi military might, the issue of toppling Saddam Hussein has slipped markedly down the agenda of even those Arab regimes most steadfastly opposed to him.

“People are indifferent, to be very frank, about Saddam. Of course, nobody approves of Saddam. But right now the priorities have shifted,” Myeena said.

Said a prominent Egyptian political analyst, who asked not to be identified: “I think you have a situation of ambivalence. On one side, you don’t like the man and his regime. But at the same time there is no sound alternative. And third, you have a threat from Iran.

“The other question is, would an attack like this weaken Saddam or in fact strengthen him? And I think if you will talk to some hard-minded people, it strengthens him. It strengthens him domestically,” said the analyst. “This criticism does not mean the non-use of force to change the regime. The question is, who uses the force, where and when.”

Arabs appear somewhat more inclined to consider the possibilities of supporting internal opposition to the Iraqi regime, perhaps by backing an opposition Iraqi militia, according to some sources. Yet they appear to be hedging their bets.

Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, who has retained a strong personal sense of enmity for Hussein, recently sent a senior diplomat to open a consular office in Baghdad.

Jordan, one of Iraq’s few Arab allies during the Gulf War, has increasingly distanced itself from Baghdad. King Hussein is said to be deeply angered at the Iraqi leader over two recent events, the murder of an Iraqi scientist in Jordan and Baghdad’s peremptory decision in May to withdraw all 25-dinar bank notes from circulation.

Yet Jordanian officials are cautioning that a campaign of military force against the Iraqi leader would only serve to unleash Islamic and Arab nationalist extremism in the region.

“Help the Iraqi people. Make pressure on the powers of the world to let food and medicines go to Iraq, but pressure Saddam for democracy. The Americans, the British, the French, if they take this line, I can bet you within months it will show results. Either Saddam will be shot, or he’ll wake up,” said Shaer.

Egyptians were more skeptical.

“It’s a noble call,” said one Cairo political analyst. “But you stand no chance . . . of inciting an Iraqi general to do anything, because a normal general is not predisposed to democratic ideals. The general that shoots Saddam will be a general who would like to replace the big man. He will not do it and immediately call for democracy.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.