More Medical Services Don’t Necessarily Lead to Better Health Care : Consumers: Americans should purchase medical care the same way they shop for other goods: mindful of getting the best value for their money.

- Share via

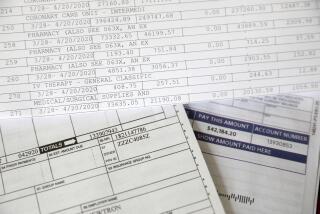

There is a simple reason why we can’t get a good deal on health care: We don’t know what we are buying, and we don’t know how much it costs.

This is in stark contrast to most industries, where providers have strong incentives to offer the best product for the lowest price because consumers demand it. The most important goal of any health-care reform proposal should, therefore, be to change the way consumers approach price and quality. Otherwise, the product will not get better and the cost will continue to rise.

One consequence of having limited information about price and quality is that our health-care delivery system is extremely inefficient. Most of this unnecessary expense, however, is the cost of health care, not of insurance or administration.

Moreover, the majority of excess cost results from over-utilizing services that offer little or no added benefit rather than from inflated prices. Economist Victor Fuchs has estimated that even drastic price cuts for physicians and drug companies would only cut total health-care spending by about 3%.

According to the U.S. Office of Technology Assessment, approximately 25% of diagnostic procedure, 25% of hospital admissions and 40% of medications are unnecessary or of questionable value.

Overuse by health-care providers is especially prevalent in settings where the providers are paid on a fee-for-service basis, but also results from high patient expectations, fear of malpractice claims and the simple fact that physicians practice in a world of uncertain outcomes.

The product we all want out of health care is health--a long, high-quality life. When we purchase health insurance, however, we buy medical services. Unfortunately, medical services are not a good proxy for health.

When we receive services, we generally measure success in ways that correlate imperfectly with improved health. For example, a drug that reduces blood pressure or cholesterol may or may not prolong life or improve well-being for a particular patient. Nonetheless, physicians and patients invest heavily in achieving these “intermediate outcomes,” especially in intensive-care units and other high-technology settings.

Even more important, there is still a tremendous amount of “clinical uncertainty” in medical care. Most therapeutic interventions never have been assessed scientifically; the Office of Technology Assessment concluded that only 10% to 20% of “routinely accepted and frequently used” procedures have been adequately evaluated.

As a result, therapies introduced with great fanfare--such as carotid artery bypass surgery to prevent strokes or the drug clofibrate for high cholesterol--frequently turn out to be useless or even harmful.

Traditional medical care focuses on treating illness rather than promoting wellness. As a result, we tend to ignore cheap ways to keep ourselves healthy and insist on expensive treatments when we get sick. Fixing this requires a health system with financial incentives to maintain health (the “M” in HMO stands for maintenance). It also requires taking responsibility for educating ourselves to live healthier lifestyles.

The health-care industry must expand its research and development activities beyond drugs and devices. For example, organized systems of care (such as HMOs) are starting to invest in information technologies that can measure health outcomes and develop better ways of delivering care. Most important, information about health and health care must be available and understandable, so meaningful choices can be made.

Understanding the quality of health care will not help us bargain effectively unless we also understand its price. There are, however, many barriers to accurate pricing in today’s health-care system.

We tend to buy health insurance rather than health services, so that the price most people and their employers pay reflects the chance of getting sick more than the cost of treatment. This practice , called “experience rating,” reduces incentives to provide services cost effectively, because the price advantage of a particular health plan derives from how carefully it is structured to cover only healthier people and less costly diseases.

Health plans offer coverage with a wide variety of benefits, co-payments and coverage restrictions that make price comparisons impossible. This is sometimes done to “select” healthier risks. For example, including dental benefits at a subsidized price may promote enrollment by people with teeth--who, statistics show, are generally healthier than people without.

There is an easy solution to problems with pricing and comparing health plans (and one that is part of the Clinton health-care reform plan). If all policies are “community rated” with standardized benefits and co-payment arrangements, consumers will choose based on the price and quality of health care services.

A more difficult problem is that most consumers do not know what health insurance costs. Because health-care benefits are fully tax-deductible only when paid by employers (self-employed individuals may deduct just 25%), health insurance is usually obtained through employment. This system makes employees less aware of the percentage of their paychecks spent on health benefits and forces employers to make aggregate purchasing decisions that often do not reflect individuals’ price-based preferences.

Consumers are also poorly informed about the cost of their services. In any system of third-party payment, employers or insurers pay, but individuals decide whether to use services--and usually pay little attention to price.

Some payers have increased deductibles and co-insurance so consumers will face higher out-of-pocket costs. Unfortunately, this often leads consumers to neglect cost-effective prevention or early treatment, only to have substantial insured costs later on.

Moreover, the prices charged for individual health-care services are inaccurate, mainly because of “cost-shifting.”

Most of the 40 million uninsured ultimately receive care--but care that is delayed, degrading, inadequate and expensive. The cost of these services is passed on as higher taxes, higher fees for paying patients and, ultimately, higher insurance premiums. For example, many uninsured patients overuse expensive emergency services because they lack access to preventive care facilities; and patients with private insurance end up being charged more by a county hospital than by a fashionable private practice in order to support the county hospital’s larger number of uninsured patients. Universal health coverage is the only remedy for cost shifting.

Tax laws also distort prices. Because there is no limit on the tax deduction for employee health benefits, health insurance seems only about two-thirds as expensive as other ways to spend one’s wages--at the expense of the federal Treasury and the budget deficit.

Understanding price and quality will let us define “value” in health care for the first time. However, we should recognize a sobering possibility: Getting the fat out of the health-care system may leave us with an even tougher problem.

If we discover that the services we want are still too expensive, we will then need to decide, as a society, how much we can afford to spend and how to allocate our resources. But we can accomplish a lot before we are forced to face that question--and if we spend 15% or 20% of gross domestic product (slightly more than the current level) this might allow us to avoid it entirely.