Genetic Explanations: A Two-Edged Sword : Is our sexual and behavioral fate in our genes?

- Share via

Seldom has science been so wrong, and so misused, as when it has come to fathoming the biological basis of human behavior. Genetics spawned the misguided eugenics movement early this century in America and Europe. Thousands of the “feeble-minded” were sterilized under U.S. law, mostly in California.

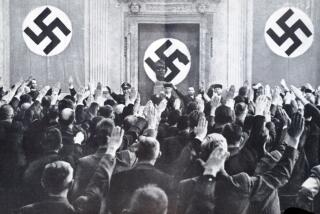

The practice ultimately was abandoned, but not before Germany copied the California law in its program to eliminate “defective” genes, part of the grotesque Nazi ethic that would underlie the effort to exterminate Jews, Gypsies and others. More recently, scientists erroneously linked violent antisocial behavior among men to an abnormal extra Y chromosome. Many men with the chromosome indeed were in jail, but actually the condition correlated with mild retardation, not criminality per se.

SCIENCE IN LAW: Now the powerful tools of modern biology have added a complex wrinkle to the heated public debate over gay rights. Two years ago, Simon LeVay, a neurobiologist then at the Salk Institute, discovered that a part of the hypothalamus was much smaller in the brains of gay men than heterosexual ones. And last year, Dean H. Hamer of the National Cancer Institute examined the chromosomes of 40 pairs of brothers who were gay and found that far more than a chance percentage of them had identical snippets of genes inherited from their mothers on their X chromosome; this suggested that male homosexuality is rooted, at least partly, in genes.

These findings are hard to interpret and remain to be confirmed, and they have been attacked from some quarters because LeVay and Hamer are openly gay. However, evidence accrues that homosexuality is immutable, not a personal choice. If so, that could bolster the argument that homosexuals should enjoy the legal protections that forbid discrimination based on race or gender. On the other hand, this research could also be used to try to “cure” homosexuality, to screen out homosexuals from the military or insurance coverage, to abort fetuses carrying a “gay gene.”

Hamer argues that sexual orientation is unlikely to be inherited like eye color, that it probably is caused by a intricate mix of genetic and environmental factors. Human sexuality is not an either-or matter, given the incidence of bisexuality.

Some scientists say that to prevent public misunderstanding, such research should not be published until fully confirmed. That is an issue that will sharpen as the federal Human Genome Project, which is attempting to chart the entire human genetic map, uncovers the genetic underpinnings of thousands of traits and disorders, opening the possibility of curing many inherited diseases.

Research results should not be withheld. But in absorbing this data it must be kept in mind that the mechanisms of human inheritance invariably have turned out to be far more complicated than originally imagined. Some ask, for example, why homosexuality is so widespread in the human and animal realms even though homosexuals seldom reproduce, and they suggest that the genetic basis of homosexuality may be linked to other traits, some highly desirable, such as creativity. Would you have aborted the fetuses that grew into Michelangelo or Tchaikovsky?

MORALITY IN LAW: Whatever the basis of homosexuality, it is foolish to think that good science will abolish homophobia. Skin color and gender obviously are governed by genetics but that has not wiped out racism and sexism. Gay rights activists skate on thin ice when they resort to science. Wise advice comes from Daniel J. Kevles, a historian at Caltech who argues that claims to social or legal rights should be based on morality and principle rather than inconclusive biology. As science peels away layer after layer of the biology that supports human behavior and expression, we should remember how science has been abused out of evil or ignorance.