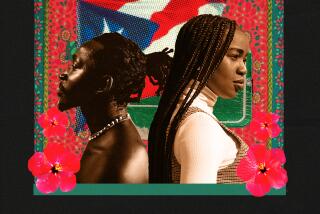

A Decision That Turned Some Heads : Barry Fletcher used a black model to win the U.S. hairstyling title, so why not for the internationals? Team officials say it was a matter of hair texture--not race.

- Share via

LONDON — Having a black woman as a model in the world’s most prestigious hairdressing competition is a sure-fire way for a stylist to lose.

That’s what the coaches of the U.S. hairdressing team told American national champion Barry Fletcher when they barred him from working with an African American model at “Hair Olympics ‘94,” the biennial world competition that concluded here this week.

It’s not a race issue, they said. It’s a hair texture issue.

The fact that Fletcher, a soft-spoken stylist and salon owner from Maryland, had won the U.S. nationals in January with a black model didn’t matter.

This was international competition, the coaches said, and the European judges would be expecting a certain look--a look that Fletcher’s favored models did not possess.

Fletcher, who is black, competed in the three-event Ladies Hairdressing Championships with a white model assigned to him by U.S. team coach Randy Rick. Despite his best efforts, Fletcher did not come close to a first-place finish.

The U.S. team of six hairdressers placed 22nd out of 34 competing countries in the ladies hairdressing events, with Japan, Germany and Russia taking the top three medals. The Americans placed fifth in the men’s hairdressing events, with Great Britain, Germany and Italy taking the top prizes. Medals are not awarded to individuals.

These championships take place under the auspices of the trade organization Confederation Internationale de la Coiffure in Paris and hairdressing trade groups in the cities where the competitions take place. The next World Congress international contest will be in Washington, D.C. in 1996.

Coming off the competition floor at Wembley Exhibition Complex after the final event, the “progressive hairstyle” competition, Fletcher was frustrated.

“I felt like I was robbed of my strength,” he said. “Obviously, I should have had a model I’m more familiar with. You should have a model with a texture of hair you’re familiar with.”

At his salon in Capitol Heights, Md., Fletcher’s clientele is about 85% black. Among those entrusting their looks to him are celebrities ranging from Tina Turner and Iman to Maya Angelou and U.S. Sen. Carol Moseley-Braun.

Fletcher said Rick told him that the kinds of styles he had in mind for the U.S. team would not work on a black woman’s hair, but the hairstylist insists that there would have been no problem had he been allowed to work with Jackie Smith, the model with whom he had won the U.S. championship.

“If she was good enough to qualify, then she should have been good enough to represent the country,” he said. “I think the judges would look at the quality of the work, the execution, the color, the total feel and the harmony of the style and fashion.”

*

Smith, who did not go to London, called it ridiculous that African American models are barred from competing. “When is it going to change?” asked the model and veterinarian from Maryland. “When do you say this is representative of American hair? When do you make a stand and say it can look stylish, it can look vogue, it can be competitive?

“I don’t see it changing if we have the same people involved,” she said.

Fletcher argued his case with Rick to no avail. He appealed to team manager Robert Niebuhr and recalled the manager’s response. “Bob said, ‘What if I let you use this black model? You go over there, you’re going to lose. Now who’s going to explain that to Matrix (the hair products company sponsoring the U.S. team)?’ ”

(Matrix said it had no involvement in the team selection process and does not believe in discrimination.)

Rick, who as team coach had final say over which models and styles the American competitors employ, said that before the competition, he went on a scouting expedition across Europe to discover which hairstyles were winning competitions. And what he noticed among the winners was the hair texture of whites.

“What am I going to do?” he said. “Go in there and say, ‘Well, I’m going to be the maverick of the world and go different?’ And then what?”

A sampling of hair officials from other countries all agreed with Rick.

Richard St. Laurent, coach of the Canadian team, said there are fabulous black models, but he understood the concerns of the U.S. coach. “Europe is different,” he said.

Asked if Fletcher could have won with his original model, British team manager Trevor Mitchell said: “They couldn’t win--it’s impossible. They wouldn’t stand a chance.”

Like others questioned, he claimed this was not a racial issue. “If (black women) had straight hair, then you could have a black model. It’s lovely to get someone with dark features on the floor.”

Rae Stuart, president of the National Hairdresser Foundation in Great Britain, said: “There are no specific guidelines. But common sense in an international hairdressing competition would suggest that you would stand a better chance with an Occidental model or perhaps a Puerto Rican or Spanish-type model rather than a Negro.”

*

Fletcher figured he spent $15,000 for his shot at being named the best in the world. He was not told until about a month before the Hair Olympics that he could not use an African American model.

“If you can’t use a black model, they should put that in writing when you fill out the application,” he said. “When we apply to compete, it costs us money. If I’d have known about it, maybe I would have changed my mind.”

Fletcher disputes the assumption that there is only one type of hair suitable for international competition, hair that is only partially representative of the world as it is.

“If we’re really going to stand up to the true meaning of our creed as Americans,” he said, “then we have to start being more open and adapting to what’s actually happening in the United States. I don’t want to have to submit to a particular level of artistry.

“It’s like if you take Michelangelo, you take his paints away and his brushes, and you say to him, ‘Now I want you to paint this chapel and I want you to use, you know, Matrix products.’ ”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.