Savoring a World of Beauty After 66 Years in Shadows : Medicine: Nearly blinded at birth, mathematician made the most of partial sight. Surgery to save it surpasses hopes.

- Share via

For 66 years, Sam Genensky viewed the world through a succession of magnifying devices, compensating for vision so severely damaged at birth he literally could not see his fingers.

Now, the Pacific Palisades mathematician lay in darkness in a hospital, his one functioning eye bandaged, his heart pounding with fear.

He had undergone a difficult operation the day before to save the sliver of sight in his right eye. But the surgery--a cornea transplant--was extremely risky in an eye as badly scarred as Genensky’s. Would he be able to see at all when the bandage came off?

At first, Genensky wasn’t sure. His brain could not immediately label the startling images recorded by his eye. Sunlight poured in from a window, splashing across the wall at the foot of his bed. He made out a chair, then the door to his hospital room, even the disarray of his bed linen.

Genensky began to cry. The surgery to save him from total blindness had done so much more, opening up a world of sight he had long ago stopped hoping for.

“I saw my daughter Marcia’s long flowing brown hair for the first time from a distance. . . . I saw my doctor’s mustache. I could make out objects around the room. Colors were incredible!” he said in an interview five months after the operation at St. Johns Hospital in Santa Monica. Genensky’s voice broke as he described that moment.

But the scientist in him recovered quickly: “Even though I could see colors before,” he explained, “there was a muddy, grayish quality to them. I just didn’t have enough acuity.”

Genensky still falls into the category of the legally blind: 20/200 vision or worse. His left eye is useless and his right eye now registers only 20/400. But for Genensky, the operation has made a profound difference, opening up panoramas where before he could only see tiny magnified bits of things around him.

One of the first places Genensky went to celebrate his new view of the world was the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena. A devoted admirer of the Impressionist school of painting, he had spent decades examining them in sections through his binoculars, then mentally assembling the whole.

“I saw the Renoirs and the Monets like it was the first time--the brush strokes, the detail, everything I had missed before! And, oh, the colors were so stunning,” he said. “It made my day.”

*

Genensky’s eyes were severely burned at birth, when a nurse accidentally bathed them with a caustic chemical, mistaking the drops for silver nitrate solution--then a routine treatment to guard babies against infections from the mother. The left eye was ruined, the right eye too scarred to be useful. But a Boston eye surgeon managed to create a pinhole opening at the top edge of the scarred cornea, admitting light to the baby’s still functioning retina.

Thus Sam Genensky made his way through school and life, resisting social and institutional pressures to gracefully accept the limitations of his eyesight.

He spent a miserable year at the renowned Perkins School for the Blind in Massachusetts after the public school superintendent in his hometown of New Bedford refused to admit him to regular high school. Required at Perkins to learn Braille, he stubbornly avoided using it, collecting every bit of printed material he could get his hands on and reading it with his nose literally pressed to the page.

“The director called me into his office one day and said, ‘Sam, why can’t you act like a well-behaved blind child?’ ” Genensky recalled. To that, he replied: “Because I am not blind.”

A new superintendent in New Bedford agreed to let young Sam try high school, but warned that there would be no concessions to his handicap in grades or the pace of instruction. He struggled through the first year, unable to see the blackboard.

In the second year, though, he hit on the idea of using his father’s World War I field glasses to magnify the board. Squinting through them from a seat in the front row, Genensky was able to see the math equations he previously had understood purely from description.

“I used these all through New Bedford High School, through Brown (University) . . . and all through graduate school at Brown,” Genensky recalled, holding the 80-year-old binoculars that he keeps handy on a shelf in his office at the Center for the Partially Sighted in Santa Monica, which he founded in 1978 to help people with limited vision.

The center was a major career shift for Genensky.

He did not set out to be an advocate for the blind, nor did he even count himself among them, though with 20/1000 vision in his sole functioning eye, Genensky was well within the legal definition of sightless.

After graduating from Brown with a doctorate in applied mathematics, he worked as a computer scientist for the U.S. Bureau of Standards, determined not to let his vision influence his career choices. “I was so bitter about the Perkins experience,” he explained. “I wanted to only be among the sighted.”

In 1958, he joined RAND Corp., working on strategic systems for the U.S. Air Force, among other projects. While at RAND, he and several colleagues developed a device based on closed-circuit television technology that enables people with severely limited vision to read and write.

Its prototype actually was built for Genensky’s own use. Users place their writing pads or texts under the camera part of the device, which instantly projects an enlarged version of the work onto a video screen. Genensky also designed glasses with telescopic lenses--a wearable version of the binoculars he carried around his neck at school.

Refinements of these and other seeing aids might have ended there, were it not for an article on the closed-circuit device in the January, 1971, issue of Reader’s Digest. The article was titled: “Sam Genensky’s Marvelous Seeing Machine.”

“We were inundated with letters--5,000 a week,” Genensky recalled. “Suddenly, after all those years of refusing to accept the label ‘blind,’ I found myself among people just like me”--people who had some sight but had access only to services for people who couldn’t see at all. “I couldn’t turn my back on them.”

Besides inventing devices to enhance vision, he was among the first researchers to document that most people labeled legally blind have some vision--data essential to rationalizing government funding and services to this population.

“The tail is wagging the dog in terms of funding,” said Genensky, backing the declaration with statistics he has put to very effective use in congressional hearings and other forums. “About 70% of the so-called legally blind (an estimated 630,000 people in the United States) . . . have enough vision to be considered partially sighted.”

Genensky, the mathematician, uses this sort of data expertly. But the torrent of statistics came to an abrupt halt one recent afternoon when Genensky happened to glance at a blackboard in the corner of his office.

Reminded of his new visual abilities, he leaped from his chair with a loud “Aha!” and grabbed a piece of chalk. A minute later, two big pie charts covered the lower half of the board, with shading in the noteworthy slices.

“I couldn’t do this a few months ago,” he said, admiring his handiwork.

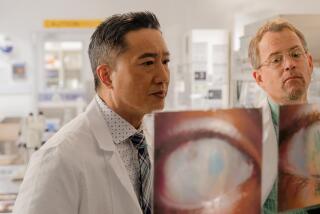

The transplant last November replaced Genensky’s scarred cornea, giving him a clearer window on the world. And from the pinhole opening created by the Boston doctor so many years ago, Genensky’s surgeon, Dr. Jeremy Levenson of Santa Monica, was able to fashion a pupil that resembles a cat’s eye slit, admitting more light and dramatically enhancing Genensky’s vision.

The eye is far from perfect. By normal standards, Dr. Genensky says his vision is downright “crummy.” He still can’t drive, has no depth perception and has trouble reading people’s facial expressions from any distance.

“But for me,” he added, “it’s a new world.”