Deborah Eidson Has Gone From Anguished Victim of Diabetic Blindness to Confident Parent and Wife. Now She’ll Comfort Those Facing Trauma. : Guiding Others in Crisis

- Share via

ORANGE — Deborah Eidson has been married for eight years but has never seen her husband.

Nor has she seen her two sandy-haired daughters, whose pictures fill the walls of her living room and who have known as long as they can remember that their mother is different.

“My mom is blind,” announced Danielle, 6. She and her sister Cayla, who is 2 1/2, rely on touch and sound almost as much as their mother does, guiding her by hand and slapping the seat when they want her to sit. They know already not to hold something up and say, “Look, mommy, look!”

Recently, Danielle summed up her mother’s condition. “It’s like electricity,” she told Eidson. “You have lights in your eyes, but the lights are turned off.”

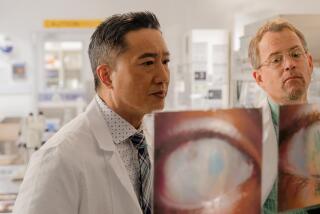

The lights went out in Eidson’s eyes in 1981, when she was 23. A diabetic since birth, she knew blindness was a distant threat, but she never thought it would happen to her. Then she started seeing black dots--”floaters” according to her ophthalmologist--and within eight months she went from having perfect vision to being totally blind.

She never thought she would marry or be a mother. After a childhood spent in and out of comas, the near-fatal labor of giving birth to her daughter, and kidney failure, she managed to adopt a second child.

And now, Eidson, who has risen above great obstacles, will be a lifeline for others facing crisis when she finishes training to be a city of Orange coordinator for Red Cross disaster services.

She was drawn to the volunteer role because it’s something she can share with her husband, Rick, who has been active with the Red Cross for years. It’s natural for her to comfort others; she can understand the emotions of fire and accident victims who find their lives turned upside down, and suddenly having to trust strangers for assistance.

Eidson knows well how the vulnerability of disaster victims can scar them for life. She is still angry with the ophthalmologist who told her bluntly and without compassion one day in 1981 that she was going blind.

“It sent me completely into a mental case,” she recalled. “From there I just went downhill. That doctor, I wish he could know what that did to me.”

Looking back, Eidson wishes she had spent her last months of sight driving up and down the coast, savoring her freedom before turning her Volkswagen Bug over to her sister, soaking in the last sunsets she would be able to see. Instead, she largely stayed in her room, crying, drugged on Valium and Codeine. Her weight dropped to 72 pounds.

That state carried over into her first weeks at Anaheim’s Braille Institute, which would give her the skills to regain as much of her previous independence as she could. Just learning how to walk and orient herself in the dark, along with learning to read and write in Braille, would take months. Mastery would take years.

“It was horrible for me,” she said of those first weeks at the institute. “I would just sit there crying all day long. Then I took myself off all the medication by myself. . . . I started to enjoy it after a while. I saw other people had dealt with this and went on with life.”

Going on with life meant relearning all the mundane chores that make up a day. One time she couldn’t find her way out of a square-shaped shower and had to sit on the floor until the panic subsided.

“It was the little things,” she said when asked what she feared losing. “I never thought, ‘Boy, I’ll never be a world-famous doctor now!’ I was washing dishes one night and I wondered how I would be able to do that.”

Eidson now washes dishes and maneuvers around the house with arms outstretched, trusting that her daughters have followed orders and kept their toys out of her step. That kind of trust is relatively easy for her. Trusting in strangers is harder.

One of her first dangerous experiences came when she was learning to navigate the streets and sidewalks with her Seeing Eye dog, Kashmir. The sidewalk led to a freeway on-ramp and, suddenly, she heard cars honking and felt the wind as they whizzed by. She stopped, paralyzed with fear. “I was shaking and I just stood there crying,” she said. “A family in a station wagon stopped and I got in. Even with a family, I probably shouldn’t have done that. That was a lot of trust for me.”

There was also the time a man came to fix the plumbing and she felt such ominous feelings from him that she called a neighbor to come over. Even more unnerving is having to trust others to watch her kids.

At home, an alarm box lets her know when one of the children has opened the front door, the only door in the house that leads to a yard that is not gated. The same box also serves as a security alarm at night, a mixed blessing when her husband, a software engineer, is on one of his business trips that can last several weeks. She has called 911 more than once when she could not pinpoint a noise, and it is one of her worst fears.

“Now I wonder if I really want to know if someone comes in,” she said with a laugh. “If somebody did come in, what would I do? I just got to the point where I can say, ‘It’s in God’s hands.’ ”

Her fears now center on her children’s future. “I worry about social things,” she said. “I want them into Scouting and ballet and my husband has to work, so I know it will be up to me to get them places. I don’t want them to have a restricted childhood because of my restrictions.”

Usually, she added, she keeps the worry to a minimum. She runs the household with the help of her Braille writer, which resembles an old-fashioned manual typewriter, and a Braille device that prints out plastic labels for cassettes, books and food jars.

Eidson said she has always been a strong, rebellious woman. She had a baby even though the doctors told her it might kill her and the baby would suffer abnormalities. She refused to write a letter--to explain her fitness as a blind mother--to the one adoption agency that would consider her. “I thought I should be able to do it like anyone else,” she said.

And she found, through open adoption, a birth mother who was acquainted with a blind woman who was raising a child, and thus felt confident of entrusting Eidson with Cayla when the girl was 3 days old.

Her “weak spells,” as she calls them, overcome her about every six months. Then her husband helps her recount all the good things she has in her life. But what really does it, she said, was getting on the county bus service for the handicapped.

Someone limited to a wheelchair or facing other mobility limits will sit next to her and she thinks, “At least I can walk,” she said. “That always pulls me right out of it.”