PERSPECTIVE ON ISLAM : A Witch Hunt in the Name of Allah : Extremists use sanctimony to justify barbarous acts, like encouraging the murder of Taslima Nasrin.

- Share via

The government of Bangladesh would have us believe that if Islamic extremists carry out their threat to kill novelist Taslima Nasrin, who is alleged to have made a blasphemous remark about the Koran, then she certainly has it coming to her.

Nasrin, a 32-year-old feminist whose writing has offended conservative Bangladeshis, is currently in hiding from the fanatics who have put a bounty of $10,000 on her head. The government, far from protecting her, is searching for her so that it can subject her to its own charges of insulting religion.

Last week, the Bangladeshi ambassador to Washington denied that his government, in pursuing Nasrin, was capitulating to fundamentalism. He acknowledged, however, that “voices are being raised making blasphemy punishable by death,” implying that his government is considering such a law.

The hard-line fundamentalists, whose audacity has been growing steadily in the Islamic world, defend their zealotry toward Nasrin with the claim that they are upholding the purity of their faith. In fact, Islam has lived very nicely for 1,300 years without imposing a death penalty for blasphemy, and it surely faces less jeopardy from Nasrin’s literary indiscretions than from the excesses of her persecutors.

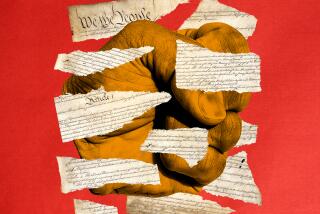

Whether in Bangladesh or elsewhere in Islam, the fundamentalists are not so much promoting piety as seeking political power. They differ from other political parties only by their exploitation of religion. In contrast to the tolerance of the Koran, they have shaped their own doctrine, calling it the “true” Islam. Self-righteous and mean-spirited, it contains a strain of violence that threatens to undermine all of Islamic society.

This violence is directed not simply--perhaps not even predominantly--against the body. This extremism targets its terrorism on the mind, seeking to keep Islamic society in the intellectual backwaters where it has stagnated for centuries. The extremists’ aim is to stifle any challenge to orthodoxy, any loosening of the cultural status quo.

In 1992, extremists killed Farag Foda, one of Egypt’s creative Islamic thinkers. In Algeria, they have murdered scholars and poets. In Turkey, their target has been outspoken journalists. Their success can be measured by the silence of Muslim intellectuals in Nasrin’s case, and earlier in Salman Rushdie’s.

No doubt the secular politics that the fundamentalists decry has been a disappointment to Muslims. In the decades since decolonization, the governments of the Islamic world have been overwhelmed by the problems of overpopulation and underdevelopment, which they have aggravated by their own incompetence and corruption. The need for a new vision is obvious; the fundamentalists have been quick to seize the opportunity.

What they offer, however, is little more than a slogan: “Islam is the answer.” Meanwhile, they have no economic program to confront the problems, and while demanding elections, they acknowledge that they will suppress democracy as soon as they take over. Society needs to punish Nasrin’s impiety, they say; but would Bangladesh, long pitied for its intractable poverty, be any better off after she is gone?

The Bangladeshi ambassador said that what his country does with Nasrin is none of the world’s business. But the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights, representing current international standards, affirms her right to free thought and expression, and the world can hardly accept the fundamentalists’ claim that their harsh view of Islamic law supersedes it.

Support for human rights is a pillar of American foreign policy, practiced in behalf of dissidents in the Soviet Union and, more recently and with some risk, in China (leading to a confrontation from which we backed away). But in dealing with Islamic extremism, the Clinton Administration has adopted a notably low profile. Does it hold that Nasrin’s rights are of a lower order than the rights of dissenters to communism?

Some Islamists have argued that the West, since the Soviets’ fall, has made fundamentalism its new bogey. Such a claim begs the issue. The quarrel involved here is not with religion or its interpretation. It is with the sanctimony that the practitioners of extremist doctrines have adopted to justify barbarous acts--like encouraging the murder of Nasrin.

The damage that Islamic extremism can inflict is not limited to Muslims. Human rights and democracy are an uncertain vision in dozens of countries. Triumphant extremism in Islam can inspire a worldwide rise of terror that undermines these values everywhere. The reverberations of the Nasrin case go beyond the borders of Bangladesh. They should be a warning to all of us.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.