China, Vietnam Hold Formal Talks on Longtime Land and Sea Disputes : Asia: Oil drilling rights in the South China Sea are main issue. Dialogue may help ease ancient conflict.

- Share via

LANG SON, Vietnam — The narrow valley that cuts through the sheer cliffs and rugged limestone outcroppings on the border separating China and Vietnam is known today on both sides of the frontier as Friendship Pass.

But for centuries, China’s most important southern pass, only 100 miles northeast of Hanoi, carried more belligerent names, such as Conquering Barbarian Pass and Conquering South Pass.

This was the traditional route for invading Chinese armies. No other place better symbolizes the long-standing enmity between China and Vietnam, which has never forgiven 1,000 years of Chinese rule that ended in 939 A.D.

Chinese and Vietnamese officials met in Hanoi this week to discuss their land and sea boundaries, agreeing to disagree but to keep on talking.

“These talks have brought about better understanding of each other’s positions,” Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Ho The Lan told reporters. “However, it is impossible to reach agreement on such complicated questions within one or two negotiations. The two sides agreed to continue their study and negotiations.”

Few specifics were reported as to points that the two sides discussed. But China’s official news agency reported that the parties “reached some common views,” including not using force to settle their dispute and keeping up a dialogue.

They apparently reached no consensus on what was clearly their hottest topic: their feud over oil drilling rights in the South China Sea. Both countries claim the same stretch of water. Both have hired American oil companies to exploit it.

Although there may have been few immediate results, the meeting was significant, if only because it was the first time that the two Communist countries have held formal negotiations on the difficult question of maritime boundaries.

U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Winston Lord recently listed the dispute between China and Vietnam over the South China Sea as one of the three main threats to peace in Asia, along with the nuclear threat in North Korea and civil war in Cambodia.

Nearby Southeast Asian countries see the negotiations as a ray of hope in the effort to resolve one of Asia’s most intractable problems.

But the talks took place against a backdrop of mutual suspicion and mistrust, which have marked relations between Asia’s traditional enemies for centuries. Two previous negotiations, in 1974 and 1977, called to discuss land border issues both ended in failure.

Adding to the difficulty are fears in Vietnam that whoever tries to succeed China’s ailing, 89-year-old leader, Deng Xiaoping, may need a military adventure to win the support of the powerful Chinese army factions that are the heart of the country’s power structure.

“It’s what happens after Deng dies that worries us most,” said a military official in Hanoi.

They remember that in 1979, only one year after he was recognized as the successor to Mao Tse-tung, Deng launched a brief, bloody war against Vietnam--China’s traditional foe--that helped him consolidate his power. Never mind that the invasion was a military failure, thwarted by Vietnamese forces here in Lang Son, that cost the lives of several thousand Chinese soldiers.

Vietnamese fears of Chinese ambitions in the region have been stoked by recent front-page articles in the Chinese People’s Daily newspaper praising the heroic dedication of Chinese soldiers “serving the sacred territory of our great motherland” in garrisons stationed on the disputed Spratly Islands.

According to Nghia Le Xuan, chairman of the Vietnam Border Committee charged with negotiating territorial disputes with the visiting Chinese, the Vietnam government is also alarmed by the recent publication in China of several books detailing proposed strategic battle plans for the capture of the Spratlys--which the Chinese call the Nansha Islands--and even the invasion of the Vietnamese mainland.

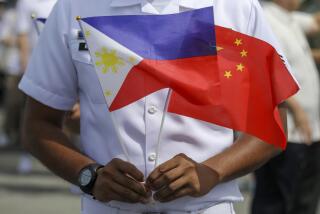

In addition to Vietnam and China, the chain of minute atolls and spits of land that make up the Spratly Islands is also claimed by four other countries--Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Brunei.

Although marked as “classified,” the books detailing the Chinese strategies are readily available in bookstores in Guangzhou (formerly Canton) and other southern Chinese cities where the feeling of Chinese manifest destiny is strongest.

Chinese officials, meanwhile, contend that Vietnam’s fears are unfounded. To demonstrate their good faith, the Chinese have proposed to temporarily “shelve” territorial disputes in the South China Sea so that the mineral resources can be developed jointly and cooperatively.

Foreign military experts contend that, in fact, China does not yet have the long-range military resources needed to enforce its claims in the Spratlys and adjacent areas.

Chinese claims on the Spratlys, some diplomats contend, are part of a complex lobbying effort by factions of the military to upgrade its equipment.

Important senior officers in the Chinese military have argued in recent years for the creation of a “blue water” navy, including aircraft carriers and long-range naval aircraft to defend their vast claims in the South China Sea.

On the agenda for negotiators, led on the Chinese side by Deputy Foreign Minister Tang Jiaxue and one the Vietnamese side by Deputy Foreign Minister Vo Quang, were three areas of dispute--the 690-mile land border, territorial disputes in the Gulf of Tonkin and issues involving the South China Sea.

Regarding the land border, both sides have agreed in principle to observe the boundaries set in an 1897 treaty signed between the Qing Dynasty and the French colonial government in Vietnam. But according to the Vietnamese there are 236 places on the border where China has crossed the 1897 line, including territory never returned after the 1979 invasion.

Talks on the Gulf of Tonkin are still at a preliminary stage.

The most bitter dispute centered on the South China Sea. Here the two sides cannot even agree on a name. The Chinese call the body of water Nan Hai (South Sea), and the Vietnamese term it Bien Dong (East Sea). The two names clearly reflect the different geographic perspectives.

In particular, the Vietnamese are infuriated with the Chinese for granting an oil exploration concession to Colorado-based Crestone Energy Corp., in an area they claim is on their continental shelf. The Chinese call the area Wan’An. To the Vietnamese it is known as Tu’Chinh.

The Chinese claim that the territory belongs to them on the basis of their claim to the nearby Spratlys. They claim that Vietnam, in fact, has violated Chinese territory by granting an adjacent area for exploration to Mobil Oil Co.

But Chinese officials say they are willing to compromise and work jointly with Vietnam to develop the 25,155-square kilometer body of water 168 miles off the Vietnamese coast.

So far the Vietnamese have reacted icily to the Chinese proposal to share the area.

“The Chinese say they want to ‘shelve’ the dispute,” Nghia snapped, “but they are aimed at our continental shelf.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.