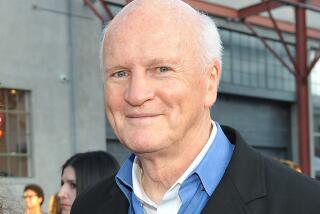

Art Collector and Philanthropist Weisman Dies

- Share via

Frederick R. Weisman, a self-made multimillionaire who amassed a fortune by distributing Toyota automobiles and spent much of that wealth on contemporary art and philanthropy, has died. He was 82.

Weisman died Sunday evening at his Holmby Hills estate after a long battle with pancreatic cancer, the family announced Monday.

A high-profile donor who gave huge sums to cultural and social organizations, Weisman lived to see his name emblazoned on museums, galleries and social service institutions from Los Angeles to Paris. During 1993 alone--as his health waned and his generosity hit its peak--his gifts of artworks and money amounted to nearly $20 million.

Pepperdine University in Malibu and Weisman’s alma mater, the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, have art museums named for the flamboyant collector. Pop artist Claes Oldenburg’s “Spoonbridge and Cherry,” the engaging centerpiece of the Walker Art Center’s renowned sculpture garden in Minneapolis, is a gift from Weisman.

The San Diego Museum of Art and the New Orleans Museum of Art contain Weisman gallery complexes as well as artworks donated by him. The new American Center in Paris, which opened in June in a building designed by Los Angeles-based architect Frank O. Gehry, was launched with a $5-million gift from Weisman.

Between 1975 and 1993, Weisman gave the Los Angeles County Museum of Art 34 contemporary American works, rare Japanese screens, scrolls and woodblock prints whose value has escalated five or tenfold. He was a longtime LACMA trustee.

In addition, Weisman amassed one of the nation’s largest private holdings of contemporary art. It was not immediately clear what will happen to that eclectic private collection of about 800 paintings and sculptures, said Eddie Fumasi, curator of the Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation. After several attempts to build a new institution failed, Weisman had hoped to turn his home into a museum displaying the works.

Weisman’s $1-million donation in 1993 to the Venice Family Clinic, which provides free medical care to the working poor and homeless, funded an endowment and a challenge grant to purchase property for the clinic’s Frederick R. Weisman Program of Psychosocial Services. Weisman also gave $1 million each to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington and the Wilshire Boulevard Temple in Los Angeles.

These monuments bear testimony to Weisman’s desire to be remembered as more than “some rich guy who sits around,” as he put it, and to set an example for the wealthy.

“I always regarded it a privilege to be able to support charitable causes,” he said in a 1993 news release outlining his philanthropic activities. “Today I believe in that more strongly than ever, and I hope very much that more and more of our country’s successful business leaders come to share that view.”

Weisman’s associates remember him as a dynamic businessman whose presence in the art world was marked by enthusiasm, independence and a need for recognition. He endeared himself to artists by helping them in lean years and following their careers, said Henry Hopkins, chairman of UCLA’s art department, director of the UCLA/Armand Hammer Museum and Cultural Center and former director of the Weisman foundation.

Weisman was born on April 27, 1912, the second of Russian-Jewish immigrants William and Mary Zekman Weisman’s three sons. William Weisman got his start in business as a newsboy but moved up to a comfortable, middle-class lifestyle as he acquired property in Minneapolis, including a hotel, a mercantile business and a bank.

Mary Zekman Weisman took her three sons to Southern California on summer vacations and moved to Los Angeles with the boys in 1918, when Frederick was six. She was a stickler for good education, Weisman recalled, and insisted on the best private schools, even if that meant sending her Jewish sons to Roman Catholic institutions.

After graduating in 1929 from Los Angeles High School, Frederick Weisman attended UCLA for a year but failed to apply himself to his studies. He transferred to the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis the following year. Although he worked part time in a hotel owned by his father, he couldn’t afford to finish school during the Depression, so he dropped out in 1930 and returned to Los Angeles.

Weisman loved to tell how he obtained a middle name--Rand-- during his college days: He plucked it from the Rand Building, Minneapolis’ tallest structure, as a symbol of his high aspirations.

His first independent commercial venture was a small wholesale produce business in Los Angeles. After his marriage in 1938 to Marcia Simon (who died in 1991, 10 years after the couple divorced), Weisman sold the business and went to work for her brother, the late Norton Simon. Val-Vita, Simon’s small canning company, merged with Hunt Brothers Packing Co. and became known as Hunt Foods and later Hunt-Wesson. Weisman became president of Hunt Foods at 31 and stayed with the firm until 1958, when he struck it rich with an investment in uranium.

For the next 12 years, Weisman tried his hand at various ventures. He formed a partnership that founded Cal-Financial, a savings and loan association, purchased racehorses and the Tanforan racetrack near San Francisco, and developed a line of drugstore consumer products that he later sold to Boise-Cascade.

But he achieved his greatest financial success as head of Mid-Atlantic Toyota Distributors Inc. Investing $100,000 in a 20-year franchise, Weisman in 1970 became one of three American distributors of Toyota products. His territory included Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and the District of Columbia, where he marketed cars and trucks through 121 dealers. In 1987, the Frederick Weisman Co.--a holding company for Weisman’s various business interests--was the largest privately owned revenue producer in Maryland, grossing $1.1 billion in sales. In addition to the automobile distributorship, his empire included a real estate concern, an insurance firm and a computer company.

Under terms of his agreement with Toyota, Weisman reluctantly sold his franchise back to the company in 1990.

As his financial empire boomed, Weisman spent millions of dollars on purchases of contemporary artworks. He and Mrs. Weisman became a major force in Los Angeles’ art community, supporting artists by purchasing their work, serving as museum trustees and hosting events that brought prominent art-world figures to their home.

The Weismans began collecting art in the late 1940s, and soon gravitated to European modernists and American Abstract Expressionists. Their purchases included works by such celebrated figures as Pablo Picasso, Max Ernst, Clyfford Still, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman and Willem de Kooning. As the couple became increasingly involved in Los Angeles’ art community, they also bought many works by Los Angeles-based artists.

In one widely publicized incident, which has assumed folkloric status in the art world, a drawing is said to have revived a seriously ill Weisman. He had been knocked unconscious in 1966 during a brawl at the Beverly Hills Hotel’s tony Polo Lounge. According to the story, he lay abed at Cedars-Sinai Hospital for several days without recognizing friends or family. But when his wife brought their Jackson Pollock drawing to the hospital because she knew he was particularly fond of it, he sat up and said, “Jackson Pollock, I remember when we bought that.”

He was on the mend, and the experience inspired the couple to establish a visual arts program--including temporary exhibitions and gifts of art--at the hospital.

The Weismans split their collection when they divorced in 1981.

Collecting on his own, Weisman became known as a globe-trotting acquisitor who bought art impetuously and voraciously on business trips. During the 1980s he flew around the world in his company Jetstar, which was an artwork in itself. Artist Edward Ruscha painted the outside of the plane as a starry midnight sky; Joe Goode transformed the interior into a pale blue sky graced by fluffy white clouds.

To make more space for his massive private collection, Weisman had covered the windows and doors inside his home. He hung paintings by Ruscha, Kenneth Noland and James Rosenquist on ceilings. He installed gigantic “Adam” and “Eve” bronzes by Fernando Botero alongside his swimming pool and set other sculptures outside windows, so that they could be seen from inside the house.

With a taste for big, boisterous, humorous artworks, as well as sober abstractions, Weisman installed realistic sculptures by Duane Hanson and John d’Andrea that were mistaken for actual people. He spoke to guests in hushed tones when he encountered d’Andrea’s nude couple in a bathroom, as if to avoid disturbing them. Window washers, unaware of the collector’s wit, saw Hanson’s sculptural likeness of an old man dozing in the board room of Weisman’s Century City office and reported that the man was dead.

Weisman took great pleasure in art but had difficulty accounting for what he liked. “It’s awfully hard to explain what art is,” he said last year. “To me, it’s art when it just moves me all over. I can’t say I like something because of its texture or color or anything like that.”

Weisman married Billie Milam, an art conservator, in 1992 at a ceremony in New Orleans, where the couple has a second art-filled home.

Over the years, he provided major financial support to the Devereux Foundation, which cares for two of his three children, Nancy and Daniel, who are severely handicapped.

In addition to his wife and the two children, he is also survived by another son, Richard, of Los Angeles; a brother, Theodore, and three grandchildren.

Funeral services are scheduled for 2 p.m. Sunday in Wilshire Boulevard Temple, 3663 Wilshire Blvd.

The family has asked that any memorial donations be made to the Venice Family Clinic, the Wilshire Boulevard Temple, the Frederick R. Weisman Museum of Art at Pepperdine or the Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.