Baltic Ferry Route Resumes Though Memory of Tragedy Haunts Nation : Estonia: Passengers on new vessel pay respects at site where more than 800 died. Victims’ families call firm, government callous.

- Share via

TALLINN, Estonia — The customary dance band was not aboard when the Mare Balticum left this port Friday night. Few of the fancy big ferry’s 438 passengers and crew were in a mood for live music. Some clutched bouquets. They were sailing to a wake.

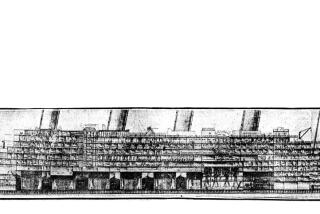

Crossing the dark, frigid Baltic en route to Stockholm, Capt. Erich Moik planned one stop, around midnight, near the place where another ferry, the 15,500-ton Estonia, listed violently and plunged to the bottom on Sept. 28 in Europe’s worst peacetime disaster at sea. There, at the sound of a foghorn, the flowers were to be scattered to the waves.

“I will be thinking of my friends as we pass over them,” said the captain, a gentle man with thick gray hair who stood erect on the bridge with both hands behind his back, gazing into a calm sea. “I lost all my friends out there,” he added softly. “All my friends.”

Six weeks after its namesake vessel pulled at least 885 people to their deaths, this tiny seafaring nation resumed the popular Tallinn-Stockholm passenger run Friday by launching the Mare Balticum, a slightly smaller luxury ferry refurbished with $3.8 million worth of new safety features.

But the captain’s sentiments, echoed by many aboard and many more on shore, gave only a hint of the trauma his country feels--and is just starting to come to grips with--in its fourth year of independence.

Estonia’s 1.6 million people, who had come to think of themselves as the most Western and progressive of former Soviet republics, feel not just grief for the 300 or so Estonians lost at sea, but a shattering sense of relapse into the worst characteristics of their Communist past.

For an aspiring annex of Scandinavia, a nation with the most vibrant economy and stablest currency among Moscow’s former subjects, the disaster exposed painful inadequacies--from questionable seamanship to the Soviet-style confusion, still unclarified, over exactly how many people left aboard the ferry that night. Most of the dead were from Sweden, a society many Estonians want to be like.

Worse, the boat flew the country’s flag and bore its name--a reminder televised recently from a robot camera that panned the wreckage showing the enormous black letters E-S-T-O-N-I-A. “For years, foreigners will associate the word Estonia with a shipwreck,” political analyst Riho Laanemae wrote in the Estonian Express.

Estonians among the 136 survivors and those who lost loved ones complain of Soviet-like defensiveness, secrecy and callousness on the part of the state-owned Estonian Shipping Co. and government agencies handling the disaster. The company monopolizes the Tallinn-Stockholm line through a joint venture with Sweden called Estline.

No Estline official attended the funeral of Andres Tammes, the crewman who sent the Estonia’s Mayday signal and whose body was one of 94 recovered from the sea. His widow, Sigrid, is also bitter, because Estline paid just $40 for his funeral, less than half what it cost.

“All this worry about Estonia’s image is just a way to avoid talking about the real issues,” she said. “There should be more talk about those who died and their families.”

Estonia is hardly equipped to deal with such a tragedy. Its social welfare system is practically nonexistent, and few people have life insurance. Estline has told people affected by the tragedy to apply for payments from the ship’s Norwegian insurer, but they are slow to find legal help to do that or to file lawsuits.

Only in late November will the government start paying compensation of $75 a month, from foreign donations, to each family that lost a breadwinner. A private agency started by an Estonian newspaper is now providing more modest relief, focusing on the country’s 60 orphaned children.

“In any case, we will support these people,” said Mart Laar, who had been acting prime minister until this month. “The aid is not up to Swedish standards, but far more than in Soviet times, when no one would have helped us at all.”

Assistance has come from Finnish psychiatrists, who treat Estonians grieving for drowned loved ones. The Finns have challenged the Soviet emphasis on medication and the Estonian instinct for stoic suffering. They encourage people to vent their feelings.

“People are slowly overcoming the first stage of their grief, their disbelief,” said Anti Liiv, an Estonian psychologist who shares the Finnish approach. “Now they’re entering a stage where they feel total hopelessness on the one hand, and hostility on the other. They want assurances that someone will be . . . crucified.”

With no official conclusion yet on the cause of the sinking, Estonians have embraced conspiracy theories: Russian sabotage, an overload of smuggled strategic metals, a bomb by one mafia gang to stop another’s cargo. But Liiv said people increasingly blame the company.

The Estonia was a roll-on, roll-off ferry, which allowed cars to enter at the stern and drive off the bow. Since the accident, such ferries have been banned in the Baltic.

Investigators say the ferry sank in rough seas after its visor-like front hatch, weighing 54 tons, swung upward and broke off, causing water to rush in, tip over cars and destabilize the ferry. They hope to retrieve the hatch next week to learn whether it fell off from faulty construction, metal fatigue or speeding by the captain, which would have multiplied the force of the waves.

The new Tallinn-Stockholm ferry, taken from another Estline route, underwent modifications to weld the front hatch closed, widen the stern to add stability, improve the communication and fire safety systems and buy new life jackets that light up for night rescuers when they hit the water.

Vironia, the original name of the ferry and an ancient name for this nation, was changed to Mare Balticum to disassociate it from the ill-fated ship.

Before the Mare Balticum sailed Friday night, a retired teacher who was not taking the trip set flowers beside an unmarked, 20-foot white wooden cross that lies on a snowy knoll near Tallinn’s port. There were dozens of other bouquets there, along with small candles burning in glass holders.

She has gone to that spot nearly every day since her 36-year-old daughter went down with the Estonia. For many others, the makeshift memorial is sufficient: Let shipwreck victims stay buried at sea.

But the retired teacher comes down on the other side of an emotional debate about whether Estonia, Sweden and Finland should spend the $70 million needed to raise the Estonia and the estimated 800 bodies entombed inside.

“Without a body, it’s like there is no end to the tragedy,” she said. “Sometimes, I even imagine that she is, somehow, still alive down there.”

Michael Tarm, a Times special correspondent in Tallinn, contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.