New Drug May Ease Chemotherapy for Children : Health: CHOC research team is studying Interleukin-11 in hope it will inhibit cancer treatment’s debilitating side effects on young patients. If it works, ‘it’s going to be one of the milestones.’

- Share via

ORANGE — A team at Children’s Hospital of Orange County has embarked on a study of a new drug that could help thousands of children afflicted with cancer endure more intensive chemotherapy, prolonging and perhaps even saving their lives.

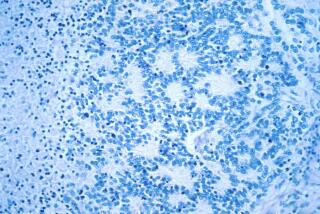

The 8-week-old study, led by Dr. Mitchell Cairo, CHOC’s cancer research director, focuses on Interleukin-11, a growth factor that stimulates platelet production in animals.

Cairo’s team hopes injecting young cancer patients with the synthesized human protein will allow them to pursue aggressive chemotherapy in children without crippling production of platelets--tiny particles essential to blood clotting. High-dosage, short-term chemotherapy is thought to be the most effective treatment against many childhood cancers. But its use has been limited because of a common side effect--a sharp decline in a patient’s platelet count which, if unchecked, can lead to uncontrolled bleeding.

“The current dogma is that if chemotherapy can be given . . . in a dose-intensive fashion, it allows the cancer cells less recovery time,” said Dr. Paul Zeltzer, a professor of pediatric oncology at UC Irvine.

If Interleukin-11 works in keeping the platelet count up, “(it) is going to be one of the milestones that could increase curing children,” he said. “It’s not the answer to cancer, but it’s one of the important steps.”

The problem, Cairo said, is that high-powered drugs used to fight cancer cells also attack other fast-dividing normal cells, including those of the bone marrow, which are involved in producing platelets. In many cases, patients require platelet transfusions.

The decline in the number of platelets can lead to delays in essential chemotherapy, and multiple transfusions can lead to immune reactions in which the child’s body ultimately rejects the foreign platelets.

Interleukin-11 is a protein discovered about five years ago in primate cells, said Jim Kaye, director of clinical research in hematology for Genetics Institute of Cambridge, Mass., the drug’s developer and sponsor of the CHOC study.

“This monkey . . . cell line was found to be secreting a protein that stimulated platelet production,” he said. Later, a human gene was cloned and used to produce the drug injected into people.

The implications of the Interleukin-11 study may be vast for the thousands of children each year who are diagnosed with tumors in their brain, bones, lymph nodes or nervous system, Cairo said.

*

But the investigation has just begun. Cairo is the principal investigator in the first phase, expected to last four months, which is intended to determine whether Interleukin-11 is safe in various dosages. Later phases will assess its effectiveness.

The initial phase will involve 22 patients at CHOC and five other cancer centers nationwide. Three Orange County patients--a 3-year-old Fullerton girl, a 6-year-old boy from the Santa Ana area and a 26-year-old South County woman--are among the first to be studied. Although the 26-year-old is not a child, she has a tumor usually found only in children.

“So far, (the drug) is safe and well-tolerated,” Cairo said. He said the known side effects are mild. They sometimes include flu-like symptoms, a fever or anemia.

Most patients in the study, although not gravely ill, are those who have tried “first line” chemotherapy that has not been effective. In the study, they are being treated with a three-drug chemotherapy regimen developed at CHOC that is gaining favor but often causes platelet levels in children to plummet.

*

If Interleukin-11 proves effective, Genetics Institute hopes to get the drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration within the next three years, Kaye said.

Zeltzer, however, cautioned that although the study is promising and worthwhile, it is too early to say what the drug’s impact will be. He noted that a hormone introduced about five years ago--on which Cairo is a leading expert--was supposed to stimulate production of infection-battling white blood cells, also depleted during chemotherapy.

But it has not lived up to its earlier promise, possibly because researchers haven’t learned the best way to use it.

“We thought we could eliminate major infections, but it has not as yet had a major impact on survival,” he said.