Templeton Prize Goes to Physicist Paul Davies : Recognition: His work bridges the realms of science and religion. Winner of $1-million award believes the universe is not a random occurrence, but a marvel of sublime order.

- Share via

Science and religion have al ways seemed like sibling rivals, disciplines whose outward antagonisms mask a deep and abiding bond of common purpose: to discern the truth about the universe and humanity’s place in it.

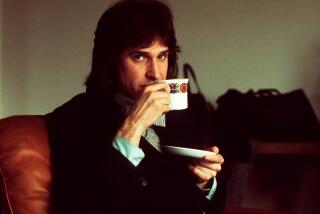

Physicist Paul Davies has been a reconciling force between science and spirit, a bridge between the realm of theology and the nature of space, time and the physical universe.

Wednesday in New York, the British-born Davies was awarded the $1-million Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion, joining Billy Graham, Mother Teresa and a handful of scientists and humanitarians who have won the prize over the past 22 years.

A mathematical physicist and professor of natural philosophy at the University of Adelaide in Australia, Davies is best known for translating the argot of quantum mechanics, black holes and time warps into everyday language and infusing those cosmic concepts with theological and spiritual insight.

His nearly two dozen books, including “God and the New Physics” and “The Mind of God” have made him one of the English-speaking world’s most popular scientists--although perhaps not among religious conservatives, who take a literal view of the biblical account of creation.

“Science,” Davies has argued, “offers a surer path to God than religion.”

“Ordinary men and women are still searching for meaning to their existence even if they have abandoned their traditional religion,” Davies, 48, said in an interview this week. “But they don’t know what to rely on. They are more likely to be persuaded by scientific arguments showing there is meaning and purpose (in the universe) than by someone pointing to ancient texts.”

Davies adheres to no standard religious creed and makes it clear that his notions of a deity are far from what many people hear in Sunday school class.

God is neither “an old man in the sky pressing a button” nor an “interventionist God,” he said, but rather a “timeless, eternal thing, an abstract notion” that lies outside the ken of conventional science.

Two years ago, Davies resigned his chair in mathematical physics at Adelaide to free himself to write, lecture and otherwise “bring the message of science and religion to the people.” He said he will use the Templeton money to support his research into the natures of time and consciousness and extraterrestrial life.

“All have far-reaching theological implications,” Davies said.

The Templeton prize, whose monetary value exceeds that of the Nobel Prizes, is funded by John Marks Templeton, a Wall Street investment fund mogul and longtime advocate of inter-religious dialogue.

The award was established in 1972 to recognize individuals who advance the world’s understanding of religion. “The prize is not for saintliness or mere good works. It is for progress,” Templeton said.

Among this year’s judges were Robert John Russell, founder of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences in Berkeley, Calif.; James Dillet Freeman, founder of what is now the Unity School for Religious Studies near Kansas City, Mo.; former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher; and former President George Bush.

In a statement, Templeton pointed to “increasing” evidence “that the universe may be dominated by creativity and purpose, just as we are dominated by creativity and purpose.”

It is that argument--that the universe is not a random occurrence but rather a marvel of sublime order--that is central to Davies’ work.

“It is impossible to be a scientist, even an atheistic scientist, and not be struck by the awesome beauty, harmony and ingenuity of nature,” Davies said in accepting the award. “How can one accept a scheme of things so cleverly arranged, so subtle and felicitous, simply as a brute fact, as a package of properties that just happens to be?

“Of course, science cannot prove the existence of a design, or a designer, but it can reveal the sheer depth of ingenuity that goes to make up this marvelous universe--our home.”

Conventional science provides the bedrock for Davies’ exploration of the nature of the universe and humanity’s role in the cosmic mystery. And while science is itself imperfect, Davies said he considers it the most reliable form of knowledge about the world.

In his own work exploring subjects ranging from the origin of the universe to the ability of human beings to understand math and science, he has found that that the idea of a world slavishly conforming to mechanistic principles is “totally inadequate.”

Consider, he says, that even minor changes in the way the universe was put together might have destroyed any chances for conscious life.

“Einstein once said that the thing which most interested him was whether God had any choice in the form of his creation, by which he meant: Could the universe have been otherwise, or does it have to be what it is? The fact that this universe is as it is, in particular that the laws permit the emergence of conscious beings who can reflect on the meaning of it all, is surely a fact of immense significance,” Davies said.

*

That means not only that religion cannot ignore scientific advances and hope to remain credible, he said, but the evidence of design and order in the world also elevates the dignity of human beings.

“For 300 years, science has had the effect of marginalizing human beings, even to the point of trivializing them,” Davies said.

But deep study into the laws of physics reveals that human beings are also part of nature, and that there is an underlying purpose and significance to human existence. “We have a genuine place in nature. I think this is cause for celebration,” Davies said.

The discovery of a transcendent order in the universe could lead to a change in human behavior, he said.

If people think there is no purpose or point in life, they are much more likely to act selfishly or with little concern for others. For some people, science can provide meaning to human existence, according to Davies.

“It matters for the universe that we’re here, that we could wipe ourselves out,” he said.

In accepting the award, Davis said scientific research “will continue to illuminate theological issues, and no religion which ignores these advances can hope to remain credible.”

And while he relies on scientific methods in his research, Davies brings a lifetime of theological reflection to his work.

Raised in an Anglican home, he attended church irregularly as a child. As a teen-ager, he read the work of Anglican Bishop John Robinson--catalyst of the “God is dead” debate of the 1960s--and spent many hours arguing with local clergy over religion. His quest to understand the “fundamental aspects of existence” led to his career in science, the Templeton organization said.

A major factor in Davies’ award, according to the Templeton group, was “his contention that humankind’s ability to understand math and science--which in turn allows for comprehension and calculation of the physical universe--evidences purpose and design to human existence. His stance is not dissimilar from that advocated for centuries by the world’s major religions.”

Despite the popular perception of science and religion being at irreconcilable odds, Davies says many scientists harbor deep spiritual convictions.

“To be a scientist is an act of faith (that) the universe is both ordered and intelligible,” he said, by way of explanation.

Why then are science and religion so often rivals, especially in the United States, where relations between the pulpit and the laboratory seem to have advanced little since the time of Galileo, Copernicus or Darwin?

“I see a big difference between the United States and the rest of the English-speaking world,” Davies said. “Because of religious fundamentalism, which is very strong in the United States, many scientists take a militaristic, atheistic line as a matter of principle because they feel they have a position to defend.

“In Britain and Australia, fundamentalism is not very visible. It’s not taken very seriously. Scientists can take a much more relaxed view about these issues.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.