Fish Offer Glimmer of Hope to Scientists

- Share via

ATLANTA — The protein that gives deep-sea fish that eerie blue glow could someday help overcome the growing danger of drug-resistant bacteria.

Biochemist John Lee of the University of Georgia and colleagues believe that their work on bioluminescence could lead to a method of striking at disease-causing bacteria in a way drugs like penicillin cannot. The lumazine protein of the deep-sea fish could provide a battle plan that invading bacteria cannot defend against.

“My guess is that you could never get around this one,” Lee said.

Other researchers called Lee’s work a novel approach but cautioned that a jump to new antibiotics is a long one.

Lee’s target for attack is bacteria’s factory for riboflavin--Vitamin B-2--which cells need to produce energy. Throwing a monkey wrench in that factory’s works would kill the bacteria, he said.

Researchers have known about one of riboflavin’s vulnerable spots, an enzyme vital for its production, but haven’t been able to figure out how to get at it. The enzyme, called riboflavin synthase, has too many functions for scientists to easily knock it out of commission, Lee said.

That line of study has been all but abandoned. But when Lee’s team recently unraveled the lumazine protein’s structure, they found that it was startlingly like that of the enzyme, although much smaller.

“The two proteins are actually cousins,” Lee said. “They apparently evolved from the same ancestor.”

There’s one important difference in how the two function. Unlike its cousin, the lumazine protein works by itself, not as part of a factory. Learning how to shut it down could lead to a way to “arm” the enzyme with another molecule and dismantle the riboflavin factory--killing the bacteria.

“Now that we have two proteins, one of which is easier to understand, we’ll focus on that one,” Lee said.

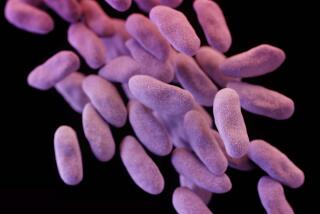

As more kinds of bacteria grow resistant to antibiotics such as penicillin and streptomycin, scientists are looking for drugs that use other methods to attack bacteria.

Lee said that because bacteria have only one way to produce riboflavin, it couldn’t develop resistance to an armed enzyme.

One of Lee’s co-researchers, Mark Cushman of Purdue University, agreed that it would be almost impossible to defend the riboflavin factory because the bacteria would have to dramatically mutate to “import” riboflavin from elsewhere.

“It would have to be pretty miraculous,” Cushman said.

But Emory University biochemist Donald McCormick, who knows of Lee’s work, pointed out that inhibiting the bacteria’s growth would not necessarily cure the disease it may cause.