Culture : Lima’s Ancient History Is Crumbling in the Sun : Houses and garbage are piled on pyramids thousands of years old. Peru shows little interest in saving them.

- Share via

LIMA, Peru — A huge hump of rocks and dirt rises abruptly across the street from Isabel Groppo’s house in the Lima neighborhood of La Florida. Groppo, 58, knows the hill is man-made, but she sees no value in it.

“People come and dump garbage on it,” she said. “It should be torn down to make room for houses.”

The hill that Groppo could do without is Huaca La Florida, a monument that was built about 3,600 years ago. Beneath its time-ravaged surface lie the angular remains of a massive pyramid.

It was as tall as an eight-story building, covering 15 acres. Its walls were faced with flat stone, plastered with clay and perhaps painted with animal-like figures. It was magnificent, archeologists say.

Many similar structures once dotted the coastal landscape that is now metropolitan Lima. They were the showcases of successive societies that flourished during the thousands of years before the Spanish conquest in the 16th Century.

Most of those impressive works are gone without a trace, but not all. Neglected ruins like Huaca La Florida remain scattered among the asphalt and concrete of today’s Lima, a city of nearly 8 million.

This is the only South American capital where such great pre-colonial structures can still be seen. But while cities elsewhere--Rome, Athens, Mexico City--proudly preserve and display their ancient ruins, Lima lets them erode, looking the other way as squatter settlements wipe them off the map.

They are the ancient Lima nobody knows. While the Inca ruins of Machu Picchu and Cuzco high in the Andes are the pride of Peru, Lima’s much older and easily accessible huacas are virtually ignored by tourists and Limenos.

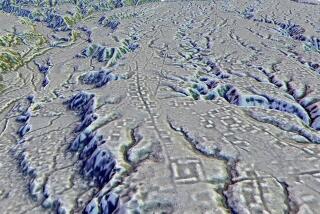

In pre-Hispanic times, the desert coast where Lima would be built was a quilt of green agricultural fields laced with an intricate network of canals and ditches. The fertile plain was sprinkled with small cities and towns, administrative complexes and multicolored monuments rising 50, 75, 100 feet and more. The biggest structures were built by thousands of workers over several generations.

Huaca La Florida, one of the first, must have made a stunning sight with its terraces and walls towering over houses and farms.

“This is the first skyscraper of Lima,” Peruvian archeologist Bernardino Ojeda said as he climbed a dusty path up the steep side of the ruins. “You can’t imagine the hundreds of millions of hours of work that went into this. . . . The effort in this monument could equal a pyramid in the Orient.”

Sometime in the past, looters dug a wide hole 30 feet deep in the center of the structure, perhaps removing examples of early pottery or weaving. In the 1960s the Sporting Cristal professional soccer club built its headquarters on adjacent land that was part of the prehistoric complex.

Hundreds of huacas have been destroyed as Lima has grown over the centuries, starting when monuments were cleared away for the colonial palace and cathedral. Archeologists plead for preservation, but hardly anyone listens.

“I don’t see any hope, because there is no solid government policy to preserve this patrimony,” said Elias Mujica, another Peruvian archeologist.

Lima, once the headquarters of a Spanish colonial viceroyalty, has always looked down on native culture, Mujica said. “There is a strong rejection of our roots.”

As a result, he said, Lima is losing the last of a rich prehistoric heritage.

The preservation of the huacas would enrich the cityscape and create major tourist attractions while saving a wealth of archeological data on past technological progress, creative glory, religious fervor, bloody warfare and back-breaking labor, Mujica argued.

“A huaca is like a book,” Mujica said. “To destroy a huaca is like burning a book, but a book that is unique, that has no copies.”

One of the most impressive pre-Hispanic sites in the Lima area was a complex known as Huaca Armatambo, in the district of Chorrillos. Built by pre-Inca inhabitants near the beginning of the 10th Century, it was occupied until the end of the Inca Empire in the 16th Century. It once covered nearly 100 acres.

“That city was very big, but nothing remains because there is a neighborhood on top of it,” Mujica said.

A few archeological studies have been done at Armatambo, but it has never been extensively excavated. The government declared it an official archeological site in 1993, but it is unguarded and unimproved.

To the northwest along Lima’s Pacific coast, in the district of Callao, slums have crept into Huaca Garagay. Built between 1200 and 1400 BC, the Garagay pyramid was 75 feet tall. Today, a large power pylon stands on the summit.

At the back of a high pyramid terrace, excavated in the early 1970s, a wall is decorated with friezes depicting human-animal figures. A wood shack covers the friezes, but its wired-shut door is easily opened.

Archeologist Jose Pinilla said the friezes are unique, the only ones intact from their period. “It’s the oldest art we have in Peru,” he said.

The National Culture Institute’s National Archeological Museum is responsible for all of Lima’s huacas , but it has guards at only seven. Fernando Rosas, director of the museum, said metropolitan Lima has 30 or 40 important huacas that still could be partly restored and 600 sites containing some remains of pre-Hispanic structures.

“The ideal thing would be to put fences around all of the monuments, but that costs too much,” Rosas said. “It would cost $15 million to fence them all.”

No one knows how many huacas have been destroyed in Lima. But Dante Casareto, an archeologist who is sites manager for the museum, said aerial photographs show enormous destruction in just one urban sector, between the Rimac River and Huaca Armatambo. In the 1940s, Casareto said, photos of the area showed 763 huacas . By 1960, 500 of those mounds had disappeared. “Now there probably are about 60 left,” he said.

Among the best-preserved pre-Hispanic ruins in Lima is Huaca Pucllana in the affluent district of Miraflores. Since 1981, the municipal government has led a project to protect and restore the huaca , which includes a 95-foot pyramid built about 1,700 years ago.

Helene Silverman, an archeologist at the University of Illinois at Urbana, said Pucllana is a fine example of how Lima could rescue its endangered huacas.

“Oh, it’s magnificent what they’ve done,” she exclaimed. If all the important huacas in the city were restored, the American said, “it would be so exciting. It would be a city of a time machine. Depending on which huaca you saw, you would be looking back 500 years, 1,000 years, 2,000 years.”

Not every huaca needs to be saved, she added, but all need to be thoroughly evaluated now. Otherwise, she said, “nothing will be left in another few years.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.