COLUMN ONE : Is Concept of Race a Relic? : Defining race by biology is misleading at best, say a growing number of scientists. New research could trigger rethinking about how public health and other social policies are applied.

- Share via

For centuries, Americans have classified themselves and their neighbors by the color of their skin.

Belief in the reality of race is at the heart of how people traditionally perceive differences in those around them, how they define themselves and even how many scientists say humanity evolved.

Today, however, a growing number of anthropologists and geneticists are convinced that the biological concept of race has become a scientific antique--like the idea that character is revealed by bumps on the head or that canals crisscross the surface of Mars.

Traditional racial differences are barely skin deep, scientists say.

Moreover, researchers have uncovered enormous genetic variation between individuals who, by traditional racial definitions, should have the most in common.

Some scientists suggest that people can be divided just as usefully into different groups based on the size of their teeth, or their ability to digest milk or resist malaria.

All are easily identifiable hereditary traits shared by large numbers of people. They are no more--and no less--significant than skin tones used to popularly delineate race.

“Anthropologists are not saying humans are the same, but race does not help in understanding how they are different,” said anthropologist Leonard Lieberman of Central Michigan University.

The scientific case against race has been building quietly among population geneticists and anthropologists for more than a decade.

This month, the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences is expected to vote on whether races really exist. The American College of Physicians this week urged its 85,000 members to drop racial labels in patient case studies because “race has little or no utility in careful medical thinking.”

But even if accepted, recent scientific findings on race cannot be expected to do away with centuries of social and political policies.

Many social scientists, medical researchers and public health experts routinely make race-based comparisons of health, behavior and intelligence--even though many of them acknowledge that such conclusions may be misleading.

As a result, the creation of racial and ethnic categories for public health purposes is becoming increasingly contentious, experts say. U.S. census officials also are snarled in an effort to redefine how people can best be classified.

“No one denies the social reality of race,” said anthropologist Solomon H. Katz of the University of Pennsylvania. “The question is what happens to the social reality when the biological ideas that underpin it vanish?”

*

“I find the term race pretty useless scientifically,” said Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza.

The Stanford Medical School scholar, one of the world’s leading geneticists, is part of a global effort to identify the thousands of genes that make up the human biological blueprint and to explore its unique genetic variations.

Cavalli-Sforza, 72, has compiled a definitive atlas of human genetic diversity. The “History and Geography of Human Genes,” which draws on genetic profiles of 1,800 population groups, is the most comprehensive survey of how humans vary by heredity.

Fourteen years spent surveying the global genetic inheritance has convinced him and his colleagues that any effort to lump the variation of the species Homo sapiens into races is “futile.”

“We have the impression that races are important because the surface is what we see,” Cavalli-Sforza said. “Scientists have been misled this way for quite a while, until recently, when we had the means to look under the skin.”

What they did not find when they looked under the skin has been just as revealing as what they did find.

Their work undermined an idea of race as old as the United States. Ever since the 18th Century, when scientists first formally codified humanity into races by skin color, “humor” or temperament, and posture, most researchers have accepted the fundamental idea that people are divided into fixed racial types, defined by predictable sets of inherited characteristics.

If this concept of race had scientific validity, researchers would expect to find clusters of significant genetic traits arranged by skin color and population group.

When scientists examined human genetic inheritance in detail, however, they found that inherited traits do not cluster and do not stay within any particular group, debunking the idea of homogeneous races.

For example, the sickle-cell trait usually is treated as a hereditary characteristic of black Africans. As a single gene, it confers resistance to malaria, although if inherited from both parents, it can lead to sickle-cell anemia. But the trait appears wherever people had to cope with prolonged exposure to malaria. It is as prevalent in parts of Greece and south Asia as in central Africa.

Even older traits such as blood type and tissue compatibility also do not correspond to any recognizable racial stereotypes, researchers said. Rather, they believe, the physical characteristics most people associate with race are the result of adaptations to climate, diet and the natural selection of sexual attraction.

“The fact you have these differences for some genetic traits doesn’t mean other differences follow with them,” said anthropologist Michael Crawford of the University of Kansas. “Racial groups don’t exist in nice discrete entities.”

*

Many scientists argue, however, that racial differences may be important vestiges of much earlier human evolution, and they point to ancient fossils and modern genes to bolster their case.

Based on fragmentary fossil evidence in Europe, Africa and Asia, some scientists suggest that modern humans may have evolved simultaneously in different regions as scattered pre-human groups interbred to form a new species. Under that theory, racial differences not only are real, but could be a million years old or more.

But that idea was dealt a serious blow recently when experts at Emory University, the National Genetics Institute of Japan and Stanford University used the evidence provided by human genes to determine that modern humans originated in Africa and began to migrate as recently as 112,000 years ago.

That means physical differences associated with race began to appear only a short time ago.

In fact, new studies show that human genetic variation is really a measure of distance--how far people have migrated from the original African homeland, adapting gradually to new conditions.

There may be no better illustration of the misleading biology of race than the example of sub-Saharan Africans and Australian Aborigines. By the color of their dark skin they would seem to be closely related. In fact, they have less in common genetically than any other two groups on Earth.

Meanwhile, scientific interest in the genetic diversity that underlies population differences around the world has never been higher.

Indeed, scientists who believe in the biology of race cite such small but significant genetic differences as evidence.

Today, scientists are discovering that a single flaw in the 100,000 human genes can cause cancer or mental retardation. Some researchers argue that the genetic differences responsible for racial variations in skin color, hair texture or body type--which account for no more than about 0.01% of a person’s entire genetic inheritance--might be equally important.

But the new research shows that such individual genes--which can exert an enormous effect on one’s health and development--do not segregate themselves into the bundles of conspicuous, inherited traits normally associated with race.

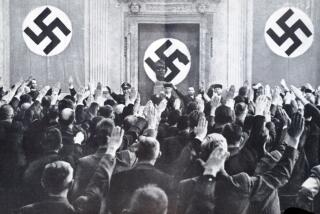

People frequently seek biological reasons for what are in fact social differences, mistaking family ties and cultural values for evidence of racial differences. Prejudices about Jews show how misconceptions about biology have been used to buttress religious and ethnic hostilities, experts say.

Anti-Semitic literature frequently treats Jews as a biological race, because they share religious beliefs and cherish certain customs as a matter of history, spiritual identity and family integrity.

As a religion, however, Judaism encompasses many ethnic and racial groups.

Nonetheless, some Jews of European ethnic origin--the Ashkenazi--do share a number of genetic traits, such as a high frequency of the gene responsible for Tay-Sachs disease.

Is this then evidence of a racial characteristic?

Experts at Yale University Medical School and the University of Washington in February used a similar, rare inherited disease among the Ashkenazi--idiopathic torsion dystonia--to reconstruct the group’s lineage, by tracing it to a single mutation more than 350 years ago. Their work suggests that the modern Ashkenazi are descended from a few thousand families in medieval Eastern Europe who intermarried.

So, the Ashkenazi are not a biologically distinctive race, but an extended family.

*

Questions about the biology of race are surfacing at a time when record immigration has revived public debate over racial identity, and second thoughts about affirmative action have led U.S. policy-makers to grapple with a legacy of slavery and discrimination.

At its most extreme, scholars say, the concept of race encompasses the idea that test scores, athletic ability or criminality somehow are rooted in racial genetic chemistry.

“Differences in skin color are often perceived as only the surface manifestations of deeper underlying differences, with respect to things like temperament, intelligence, sexuality . . . the stuff of which common stereotypes are made,” said Michael Omi, an expert on ethnic studies at UC Berkeley.

Whenever researchers focus on race--whether polling political attitudes or seeking the roots of violent behavior--they encounter troubling ethical dilemmas, experts say. If racial labels indeed have no biological meaning, then issues of scientific accuracy, consistency and bias become even more acute.

“In rejecting the biological conceptions of race, it opens up the way for us to debate how we have socially and politically thought about race and why it continues to have a hold on our imaginations,” Omi said.

“We will conduct a study about race and residential patterns, or race and arrest rates, or race and intelligence, without thinking about what social concepts of race we are using,” he said.

Although it has been decades since anthropologists explicitly supported the idea that some races are superior, research on race is still emotionally charged.

Geneticists whose work challenges traditional beliefs about racial biology find themselves accused of racism by people who worry that the research simply will reinforce the idea that any groups are different and that those hereditary differences are important.

At the same time, some anthropologists whose work undercuts racial theories find their activities dismissed by many colleagues as politically motivated.

Others contend that to deny the scientific reality of race is itself a form of racism.

Queasiness about the scientific study of race is understandable. In the past, scientists have done much to foster misguided ideas of racial biology and inherited inferiority. Biological concepts of race easily became tools of intolerance.

Many scientists defend the idea that race matters--if only as a question of academic study. But even they cannot agree on how many races exist.

“Although it may be politically incorrect to talk about race as a concept, there is reality to race, in an evolutionary, biological and historical sense,” said Craig Stanford, a biological anthropologist at USC.

“But people are so quick to equate race with racism,” he added. “The question . . . is, ‘What does race mean?’ Is there any useful concept that does not do more harm than good?’ ”

Although the study of race has traditionally been a tenet of anthropology, many of Stanford’s colleagues simply avoid the debate because political sensitivities are so raw that to conduct serious research on racial biology is to risk public censure.

“They are like astronomers who are afraid that the study of stars and planets makes them astrologers,” he said.

When Lieberman at Central Michigan formally surveyed anthropologists, however, he found that a slim majority now rejects the concept of biological races.

“That marks an enormous degree of change in the discipline,” he said.

*

As a matter of public health, racial labels still are the stuff of life and death.

Infant mortality has been about twice as high for blacks as for whites since 1950; Native Americans have substantially higher rates of death from unintentional injuries than any other group, and, compared to whites, native Hawaiians are more likely to die from heart disease, cancer and diabetes.

Blacks, Ashkenazi Jews, Chinese, Asian Indians and other groups in America can have different--and potentially dangerous--reactions to common medications such as heart drugs, tranquilizers and painkillers, said Dr. Richard Levy, vice president of scientific affairs at the National Pharmaceutical Council.

But artificial racial categories can distort even the simplest public health statistics used to frame federal policy and allocate resources, medical authorities said.

When scientists use racial designations--often created by others solely for census and other legal compliance purposes--as the basis for studies, they may unintentionally weaken their research and perpetuate racial stereotypes, health experts said.

They can find an inherited, racial linkage where none exists, or overlook the medical effects of what people eat, where they live and how they are treated, said experts at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Most medical researchers treat African Americans as a homogeneous group whose public health problems are linked to skin color, regardless of ethnic origin or family history.

In a finding often cited as evidence of inherited racial variation in health, several medical studies have determined that African Americans are at a higher risk of hypertension than whites.

Other studies, however, suggest that high rates of heart disease among black Americans may be more a matter of diet and the stress of discrimination than genes.

Dr. Richard S. Cooper of Loyola University’s department of preventive medicine and epidemiology says many black Americans are most closely related genetically to West Africans, yet West Africans do not share their higher rates of many major health problems such as heart disease and diabetes.

In all, experts have identified nine distinct black population groups in the United States that vary widely in history, economics, and social and environmental factors--all of which bear directly on health.

U.S.-born black women and Haitian-born women, for example, have higher rates of cervical cancer than English-speaking Caribbean immigrants, while both immigrant groups have lower rates of breast cancer than U.S.-born black women.

Even when groups are closely related, ethnic variations in diet can radically alter reactions to medications and other important medical characteristics.

Researchers compared how villagers in India and Indian immigrants in England reacted to the same medications. They discovered that as immigrants adopted a new lifestyle their drug metabolism became more like the English.

When CDC medical anthropologist Robert A. Hahn in Atlanta started investigating infant deaths in the United States, he quickly discovered how misleading racial labels can be.

Comparing birth and death certificates for 120,000 babies who died in 1982 or 1983, he found that many had been identified as one race at birth and another at death. In the absence of consistent scientific definitions, medical authorities and funeral directors relied on what their eyes told them.

When Hahn double-checked the records, he discovered that infant mortality among Native Americans was twice as high as public health authorities had estimated. More black babies also had died than anyone had believed.

Many public health experts such as Hahn say racial categories can be such a misleading tool for monitoring public health that such labels should be abandoned.

“I think it is important to analyze health care characteristics in terms of ethnicity, but it is important to realize what you are classifying is not race in a biological sense,” Hahn said.

“Public health people,” he added, “have not paid sufficient attention to what the scientists have to say about race.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

What’s Race Got To Do With It?

For centuries, people have sorted each other by races based on skin color. Now many scientists say that on a genetic level, race is meaningless. Researchers acknowledge important hereditary differences between people but say race does not explain them. Instead, human genetic variation is a measure of genetic distance--how far people have migrated from their original African homeland, adapting to new conditions along the way.

Human migration . . .

Experts say the first modern human beings began to migrate out of Africa about 112,000 years ago. That means the physical differences associated with race evolved only a short time ago--much more recently than many experts previously believed.

. . . as a cause for genetic variation.

A study of the genetic variation of more than 1,800 ethnic groups around the world shows that there are no distinct racial groups, only a continuous gradient of genetic change along the paths of human migration.

Direction of migration: The spectrum of color shows the gradual genetic change between major ethnic groups, beginning in Africa and ranging through Asia and the Americas.

Putting a New Face on Race

Conventional notions of race are based on skin color and geography, but genetics experts say there are many other ways to group people by their heredity. Here are a few unconventional “races”, based on widely shared inherited characteristics:

Race By Resistance: If scientists grouped people by their inherited ability to resist malaria; the so-called sickle cell trait, then the following groups would form two different races:

A) Greeks, Thai, Yemenites, Dinkas and New Guineans

B) Norwegians several black African groups

Race By Digestion: If people were grouped by whether as adults they retain the enzyme lactase, needed to digest milk, then the following two races would be created:

A) Some African blacks, east Asians, Native Americans, southern Europeans and Australian Aborigines

B) West Africans, Arabs and northern Europeans

Race By Fingerprints: If people were grouped by how they inherit certain fingerprint patterns, then the following two races would be created:

A) Most Europeans, black Africans, and east Asians

B) Mongolians and Australian Aborigines

Sources: The History and Geography of Human Genes, Princeton University Press; The Origin of Modern Humans, Scientific American Books, Discover Magazine.