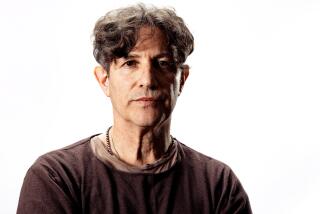

Following in His Footsteps : Medicine: Frederick Grazer of Newport Beach and other members of the Tord Skoog Society have changed the face of plastic surgery, but they credit the Swedish pioneer.

- Share via

NEWPORT BEACH — Frederick Grazer had a few people over during Easter week. It is a time in this beach town when the discourse at most gatherings largely consists of sunburned galoots chanting “Kegger!” Grazer and his guests, however, were kicking around topics such as “Correction of Severe Blepharoptosis by a Composite Flap Consisted of the Orbicular Oculi Muscle and Orbital Septum” and “My Experiences in Endoscopic Forehead Lifts.”

So it goes at meetings of the Tord Skoog Society.

Although it is not exactly a household name, to the eminent plastic surgeons--including medical school deans, heads of clinics and such--gathered here from around the world last week, Swedish doctor Tord Skoog was a giant in his field.

To Grazer, a Newport Beach plastic surgeon who has been president of the society for five years, Skoog was a guiding light.

“He was the most dynamic person I have ever met in my life,” Grazer said, talking at the Balboa Bay Club’s Governor’s Room the day before the society’s meeting started last week. As a young doctor out of UCLA in 1966, Grazer had received a fellowship to study under Skoog in Sweden.

“He was so eloquent, so precise, a fantastic teacher. Here was a man who could lecture, in English, while he was operating and never miss a word. He would say, ‘I am going to do this,’ and that would be exactly how it was done. The quality of his work was magnificent.

“All of the people meeting here think about him on a daily basis, I think. You may be doing a procedure, and in your mind you’ll see that precise way he did things, and you’ll want to be able do it as well,” Grazer said. “More than anybody else, I think he has influenced our lives.”

Inspiration shows up in the most unlooked-for places. In these cynical and cash-driven times, one scarcely considers selfless devotion to be a trait of doctors, much less of plastic surgeons, whose ubiquitous “before and after” advertisements give the impression that all they do these days is suck fat out of rich people.

They do that. Indeed, Grazer is recognized as the man who legitimized liposuction and advanced the art to its present state, though he also rails against the garish advertisements of fellow surgeons. Plastic surgery is far more, though, and Grazer sees a noble art in all of it, whether it is giving a human face back to a burn victim or performing a tummy tuck.

The plastic surgeon needs to know not only each precise function of the body--bone, cartilage and warm flesh--but also how far nature is willing to be stretched and tricked into new shapes.

Like other sciences, plastic surgery made many of its advances in wartime. Skoog studied with the leading practitioners of his time, a generation that carried the art to new heights responding to the horrific carnage of World War II. Grazer said Skoog was a nexus of that knowledge, who then pioneered several techniques resulting from his own volunteer work helping Korean War victims.

*

In 1967, Grazer and other doctors inspired by Skoog formed the Tord Skoog Society of Plastic Surgeons to honor the man and further the craft to which he had devoted his life. Particularly following Skoog’s death in 1977, the society has put its energies into teaching, including a program to support educating doctors from developing nations.

Most of those in the 85-member society worked or studied with Skoog, though they do sometimes admit new members who didn’t work with him but who show promise of excelling.

Those attending this year came from six European countries, Brazil, Korea and the United States. They meet every two years, with past congresses having been held in Athens; Katmandu, Nepal; Helsinki, Finland, and other spots that rather edge out Orange County on tourist appeal, even though the doctors and their families did repair to Disneyland one afternoon.

If Grazer’s career is any indication, Skoog’s influence on his students was a profound one. Colleagues and patients say Grazer is unconcerned with money or acclaim, although he has developed numerous surgical techniques, collaborated on medical devices now in common use, authored textbooks, taught (he is a professor at UC Irvine and Pennsylvania State University), headed numerous boards and organizations, done charity work and still finds time to make house calls.

Grazer’s father was an X-ray technician, and his grandfather was a general practice physician in San Francisco, serving through that city’s famous earthquake and fire. Grazer grew up in the Northern California town of Chico.

“When I was 4 years old, I’d hear about my grandfather and knew then it was my destiny to be in medicine,” Grazer said. When he was 13, Grazer contracted polio, and the experience affirmed his decision to go into medicine.

He did medical lab work for the Air Force during the Korean War. He later studied medicine at UCLA and did his internship at several area hospitals. He had intended then to return to his home town as family doctor but changed his mind while a resident doing surgeries at Los Angeles County Hospital.

“There I found that, while all of the other general surgery residents hated operating on burns, I enjoyed it, and came to feel it was my forte, reconstructing injured people. I think it was because I had to reconcile it with my own disability, the polio I’d had.

“And these were people with just devastating injuries, where their pain and suffering is horrendous. And after you once got skin grafted you would get them over the pain, and then they’d have these months of rehabilitation. I related to them so much that it’s been 30 years now, yet there are patients I operated on back at County Hospital that I still have contact with.”

When Grazer gave a lecture titled “Why I’m Happy I Became a Plastic Surgeon,” at Pennsylvania State University’s Hershey School of Medicine in 1991, the entire subject was the patients he still had contact with over the years.

Having been through polio (and post-polio syndrome, which hit him 17 years ago), he said, “made me a better doctor. I think that I can empathize and relate to patients more.”

Grazer, who had an ulcer on his leg years ago, had to have a skin graft. When he sees a patient who needs a skin graft, he says, “I just pull up my pants leg and say, ‘That’s what it’s going to look like.’ ”

Actually, Grazer now has several body parts he can use as examples, having himself gone in for a face lift, belly suction and eyelid surgery.

Although he mostly did reconstructive surgery when he started, these days 80% of the people who come to him want aesthetic surgery, to rectify some real or perceived slight of nature. He has operated on Academy Award winners and Las Vegas stars, and many others less in the public eye.

Costa Mesa resident Christy Carlin has known the doctor for two decades and doesn’t mind it known to the world that she went to Grazer for liposuction, breast implants and a chin implant. His impact on her life has gone beyond those things. Fifteen years ago Grazer saved her late husband’s life by performing a history-making surgery: He created a chest flap out of armpit muscles and leg grafts after his patient’s sternum wouldn’t close following heart surgery. It was a five-hour operation for which Grazer flew in experts from Pennsylvania and San Francisco to assist.

Grazer makes no great distinction between the cosmetic and reconstructive work he does, because one advances the other. Liposuction, for example, has found a place in breast replacement for patients with mastectomies, and he’s participated in research showing that liposuction can lessen the amount of insulin required by diabetics.

The Tord Skoog Society meetings are intended to keep doctors on the leading edge of such advances.

*

In his mid-60s now, Grazer says he has considered retiring but loves his work and teaching too much.

He points to his mentor, Skoog, who despite damaged health following a heart attack, worked until his death.

“You can’t think of the way he inspired us without wanting to go on and try to inspire in the same way,” Grazer said.

“I think we all feel that way in the society. These are such honorable, humble people. We speak very reverently of Skoog. We try to emulate him, but no one tries to outdo him.”