LATIN AMERICA : First Argentina, Now Chile: A Nation Looks Back in Anger

- Share via

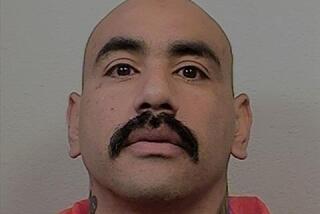

SANTIAGO, Chile — With the candor of a carpenter talking about his trade, round-faced Osvaldo Romo spoke of torturing and killing prisoners as a secret police agent under Chile’s former military government.

Romo’s matter-of-fact description of past atrocities came in a jailhouse interview with a correspondent for Univision, a Spanish-language television network in the United States. When parts of the interview were broadcast on Chilean TV last month, they stirred up a hornet’s nest.

Chileans were well aware of human rights violations by Romo and the agency he worked for in 1974 and 1975, the Directorate of National Intelligence, or DINA. But never before had a torturer openly talked about his work on television. It was a repulsive reminder of the past horrors that continue to trouble this South American nation.

Romo symbolizes the anguishing conflict between Chile’s desire to see justice done for sordid crimes of the past and its need to leave that past behind.

Romo’s interview hit Chilean airwaves at an especially sensitive moment. The Chilean Supreme Court was preparing to issue a ruling on the 1976 assassination in Washington, D.C., of Orlando Letelier, a prominent Chilean Socialist. Some Chilean army officers were said to suspect that the broadcast of Romo’s interview was part of an anti-military campaign timed to coincide with the final chapter of the Letelier case.

On Tuesday, the Supreme Court confirmed the prison sentences of two army officers convicted of ordering Letelier’s murder--seven years for retired Gen. Manuel Contreras, the former chief of DINA, and six years for Brig. Pedro Espinoza, who was Contreras’ chief of operations.

Romo was a civilian in DINA, which was created in 1974 by Gen. Augusto Pinochet’s military government. In his interview, Romo told of torturing prisoners by various methods, including electric shocks to their genitals, and of seeing some victims die under torture.

He showed no remorse, declaring that DINA’s biggest error was not killing all of its torture victims.

“I wouldn’t leave a parakeet alive,” he said.

In some ways, the interview was reminiscent of recent confessions by a former lieutenant commander in neighboring Argentina who told of throwing drugged political prisoners out of navy death flights over the sea in 1976 and 1977. Such revelations have made it clear that much remains to be said about human rights crimes under past military governments in Latin American countries.

But in Chile, Argentina and other countries, amnesties and statutes of limitations impede prosecution. A Chilean amnesty law, for crimes that occurred between 1973 and 1978, has been left standing since the transition to a civilian government in 1990.

Romo has been held since November, 1992, for investigation in a dozen cases of disappearances and deaths at the hands of DINA, but human rights lawyers fear that eventually he could be released without charges.

“All of those crimes are covered by the amnesty law of 1978, so it’s possible that the courts could release him on that basis,” said Sebastian Brett, a research associate in Chile with the U.S.-based Human Rights Watch.

So far, Contreras and Espinoza are the only ones to have been convicted of human rights crimes committed before 1978. The Letelier case was specifically excluded from the amnesty law.

After Romo’s interview, according to Santiago newspapers, an army colonel visited him with a message: Shut up. Romo later signed a notarized statement saying that he had given the interview in a mood of “desperation.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.