COLUMN ONE : Something New Under the Sun : Astronomers hope exotic tools will help them probe beneath the massive fireball’s surface. Big Bear is a hot spot for research into our nearest but oft-neglected star.

- Share via

As night snuffs out the day over Big Bear Lake in the San Bernardino Mountains, the sky lights up with familiar mythological creatures: in the canopy of constellations it’s easy to find Draco the Dragon, the Greek hero Perseus, and Ursa Major, the Big Bear (better known as the Big Dipper).

But to the astronomers in the observatory on a spit of land in the middle of the lake, these denizens of the deep sky are collectively dismissed as “the dark side.”

These astronomers start their day at dawn, when the nighttime astronomers go to sleep. And they study one special star.

It is a star that spews streamers of electrically charged particles that extend for millions of miles into space. Its nuclear furnace converts the mass of two dozen ocean liners into pure energy every second.

“It’s my favorite star,” said Caltech astrophysicist Hal Zirin, who directs the Big Bear Observatory.

The star, of course, is our sun.

As it turns out, our own personal star poses mysteries as deep as any black hole and as quizzical as any quasar.

That situation may be about to change. Equipped with exotic new technology, scientists are embarking on an unprecedented exploration of the sun.

The centerpiece is a six-station global network that will listen to the sun as it sings out in 10 million different tones. Appropriately known as GONG (for Global Oscillation Network Group), the system will allow scientists to probe under the sun’s surface for the first time. Just as sonograms use sound to peer inside a mother’s womb at a developing baby, sound waves bounding around inside the sun reveal a great deal about the star’s internal structure. The difference is that the solar sound waves are generated by the acoustics of the sun itself.

“Until now, it’s as if we were geologists and all we’ve had is a shovel; we could just poke at the dirt,” said GONG project director John Leibacher of the National Solar Observatory in Tucson. “What we’d like to know is: What the devil is going on underneath?”

Another new eye on the sun is the joint U.S.-European satellite Ulysses, which recently completed its first pass over the star’s north pole--the first time it has been viewed from that vantage point. “Solar physics is really leaping ahead,” said Edward Smith, project scientist for the Ulysses satellite for the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena.

The sun is quiet now, at the so-called solar minimum. Its next cycle of fireworks isn’t due until 2001.

“We’ve seen the simple sun,” Smith said. When Ulysses comes back for a second pass in six years [from its orbit around the solar system], “we’ll see it when it’s in its most complicated state. And that should be fascinating.”

And when the sun acts up, Earth can take a direct hit.

In April, 1984, as then-President Ronald Reagan was flying to China on Air Force One, the star flared up with such force that it scrambled radio signals and silenced the Great Communicator for hours. In March, 1989, it had blacked out Quebec for days.

Both the glowing curtains of colored lights that drape the northern skies as auroras and the magnetic storms that knock out power systems are clear evidence of solar effects. Some solar physicists even think that cycles of solar activity might affect overall global climate. A prolonged cold snap that froze much of Europe for more than 50 years in the 17th Century coincided with an almost complete absence of sunspots.

*

Learning about the sun will help scientists know more about things that lie far beyond our solar system. “The sun is not the only star in the sky,” Smith said. In fact, it’s a fairly average star, of average mass and brightness, middle-aged at 5 billion years. With a better idea of what powers the sun, astrophysicists will better understand the life cycles of all stars--information that is critical to pinning down the age and size of the universe.

But many solar astronomers say their star is being neglected for more exotic strangers in galaxies far away. Their references to “the dark side” convey a certain bitterness. “There is no glory in daytime astronomy, and yet our lives depend on it,” Zirin said. “It’s crazy.”

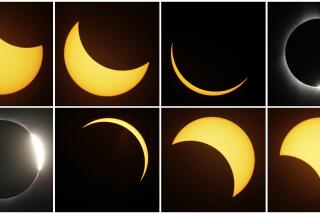

Ever since Galileo turned his homemade telescope skyward and saw that the star was not a perfectly smooth heavenly sphere, people have wondered about its unaccountable variability. For example, the sun periodically breaks out in spots. These dark splotches appear where the magnetic fields are tied up in knots, and they are often associated with solar flare-ups. But no one knows exactly how the spots relate to flares--which makes it impossible to predict when blasts of electrified particles are heading toward Earth. To unprepared astronauts, such outbursts could be fatal.

*

Moreover, the sunspots wax and wane in cycles that peak every 11 years. As the previous cycle’s fading spots linger at the sun’s Equator, new ones break out nearer the poles. But the magnetic poles of the new spots are reversed, with North becoming South and vice versa--as if the sun had turned itself inside out. Again, no one knows why or how, or if particularly active cycles could be forecast.

Like the Earth, the sun has a magnetic field that threads from pole to pole. And like the Earth, the sun rotates. But there the similarities end.

The Earth rotates uniformly once every 24 hours. On the sun, the equator rotates every 27 days, while the poles rotate every 34 days. This means the magnetic fields get twisted like rubber bands wrapped around a spool.

At the beginning of a cycle, the magnetic field looks something like a bar magnet--with clear North and South poles. But as the cycle progresses and the fields get more tangled, they get twisted into knots. The knots contain intense fields that keep heat from the sun’s interior from rising; the relative coolness of sunspots makes them appear dark. Large ones can be 30,000 miles or more across.

Because sunspots always travel in pairs, solar physicists think they are loops in the magnetic field lines that somehow pop up through the surface.

*

Based on what they could see on the surface, physicists built mathematical models of the dynamo inside the sun. In the center, the nuclear furnace burned hydrogen like a huge atomic bomb. The heat radiated through the center layers, then bubbled to the surface like boiling oatmeal. The movement of the electrically charged oatmeal created the magnetic fields, which got twisted by the rotation, creating sunspots and flares.

The models worked pretty well. Or they did until about 20 years ago, when it was discovered that the sun was pulsing in a regular rhythm; moreover, it was heaving in dozens of harmonics at the same time, and the motions seemed to be emanating from deep within its heart.

“Now, we don’t know very much at all,” said David Rust, physicist at the Center for Applied Solar Physics at Johns Hopkins University. “I think it’s fair to say at this point, people are just scratching their heads.”

Big Bear is considered one of the world’s best solar observation spots--which is one reason the last of six GONG sites was placed there this summer. The lake absorbs heat that otherwise would rise as turbulence, so the air stays relatively still; the sun shines more than 300 days a year.

On one pine-scented August day, Zirin saw the first sunspot of the new cycle at Big Bear. There also was a flare in progress--a big one. It was the sun’s hot gas spurting out of a kink in the sun’s tense magnetic skin.

Typically, a flare like this can extend for 100,000 miles and reach 10 million to 50 million degrees. Luckily, this one was blowing in the wrong direction to affect Earth.

People such as Zirin who try to figure out the sun by studying its face are dubbed solar dermatologists by their colleagues. The photos of sunspots that line the walls at Big Bear look like spreading melanomas; except these blemishes break out and fade in phases.

“The patterns we see are incomprehensible right now,” Zirin said. “A sunspot appears, but how does it get there? Why does it repeat every 11 years? It’s terrible that we don’t understand that.”

About 99% of the big flares are associated with sunspots, but no one is exactly sure why. “You see these eruptions on the sun,” Rust said, “and then between the sun and the Earth something mystical happens.” What actually hits the Earth--be it a loop of magnetic force or a cloud of particles--”is a matter of intense debate and much confusion,” he said.

*

Rust and a student recently discovered a new property of flares that might help scientists to better understand and predict them. When solar eruptions sling clouds of electrified gas into space, the clouds appear to preserve whatever “twist” was present in the original flare. “The sun is sort of throwing its DNA at us,” Rust said. “It’s like a Slinky; once it’s twisted, it’s really hard to untwist.”

By tracking the direction of the twist of a particular disturbance as it starts on the sun, observers can calculate its temperature, density, magnetic field and tell just how destructive it will be when it strikes the Earth.

Zirin’s research focuses on yet another kind of surface effect--the sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona. This wispy halo of extremely hot gas occasionally lets loose with magnetic clouds known as “coronal mass ejections”; they cause less disruption on Earth than the magnetic storms produced by flares, Leibacher says--more like strong gusts in the solar wind.

But no one can explain how the coronal gas gets so hot. The temperature on the surface is about 5,000 degrees; “Then all of a sudden, it takes off to a million degrees in a process we don’t have a clue about.”

Zirin and others think the answers might lie in the hundreds of thousands of tiny tendrils that rise to 6,000 feet above the surface, perhaps carrying hot gas. Zirin studies the images on his screen; these spicules stick out from the surface like the fuzz on a peach.

Clearly, predicting solar storms that can harm the Earth will remain elusive as long as the forces behind flares and coronal mass ejections remain mysteries. For Zirin and others, the key is keeping a constant eye on the surface.

They still mourn Skylab, the U.S. space station that, ironically, was brought down by the actions of the sun. Like all satellites, Skylab orbited above the Earth’s atmosphere--to avoid drag. When the sun breaks out in flares and spots, our atmosphere heats up--and rises like a cake. Therefore, satellite operators need solar forecasts in order to boost their spacecraft to higher orbits.

Skylab was a 24-hour orbiting solar observatory launched in 1973. (Much of the equipment in the Big Bear observatory is NASA leftovers, Zirin said.) But in the late 1970s, a particularly active sun puffed up the atmosphere. Unprepared, Skylab got dragged back to Earth by friction from the air. It spiraled closer and closer to Earth and eventually burned up over the Indian Ocean. By July, 1979, Skylab was toast.

One probable reason for its downfall, William Marquette said, is that “the predictions [of solar activity] were lousy.”

*

But no matter how well the solar dermatologists learn to diagnose the surface, other astronomers don’t think they will really understand the star until they examine its internal structure. Thanks to GONG, that now seems possible.

Listening to sound waves from the sun wasn’t even thinkable until the 1960s, when Caltech physicist Robert Leighton noticed regular pulsations on its surface. Even in quiet times, the sun has a nubby texture like an orange’s skin. Each nub is a continent-sized bubble of hot gas moving toward or away from the center. Leighton saw that patches moved up and down with five-minute periods. A decade or so later, astrophysicists learned that in fact the entire sun was pulsing like a heart.

Each of these rhythms corresponds to a specific path of pressure waves inside the sun. Imagine a bubble of gas rising from the sun’s interior. As it hits the surface, it reflects back--like ripples from a stone on the surface of a pond. As it moves up and down, it sets up a standing wave that lingers, sometimes for hours, even days.

“Some things come up and down predictably all over the sun and at the same time,” said assistant GONG project manager Robert Hubbard. This “new sun” with its well-organized wave patterns was a radical departure from the “old sun” described as a caldron of boiling oatmeal, Hubbard said.

The waves that bounce around inside the sun are like sound waves in an organ pipe. The tone will differ depending on the temperature, composition and density of the air inside.

“The sun is like a spherical organ pipe,” Hubbard said. And because it vibrates in three dimensions, it sets up a rich array of frequencies, 10 million to be exact.

*

With all those frequencies, the astronomers get far more information than they would from a single inside look--just as a single X-ray gives far less information than computerized axial tomography (a CAT scan). Each GONG detector tracks the motion of nickel atoms as they bob like buoys in the sun’s fluid atmosphere. Once a minute, during sunny days, each snaps an image. Images are sent to Tucson to be fitted together into a picture of the sun’s innards.

As a bonus, GONG should be able to “hear” storms brewing on the opposite side of the sun--much as geologists can detect earthquakes (or atomic bombs) going off on the opposite side of the Earth. For now, GONG is just a technology, “like steel,” Leibacher said. “You discover it, and then you make a pliers out of it. We have demonstrated that the technology works. Now we’re ready to put the technology to work to go exploring.”

And as GONG gears up, Ulysses will be flying toward Jupiter, then back to the sun again just in time for solar storms that should be bigger and better than ever. With luck, the satellite will pass by in time to see the magnetic poles disappear and reverse--never seen before from a polar perspective.

The sun worshipers at GONG and Big Bear will be watching.

“It’s the old business of the blind people and the elephant,” Leibacher says. “We’re all trying to figure out what we’re looking at.”